What are the famous Assyrian reliefs?

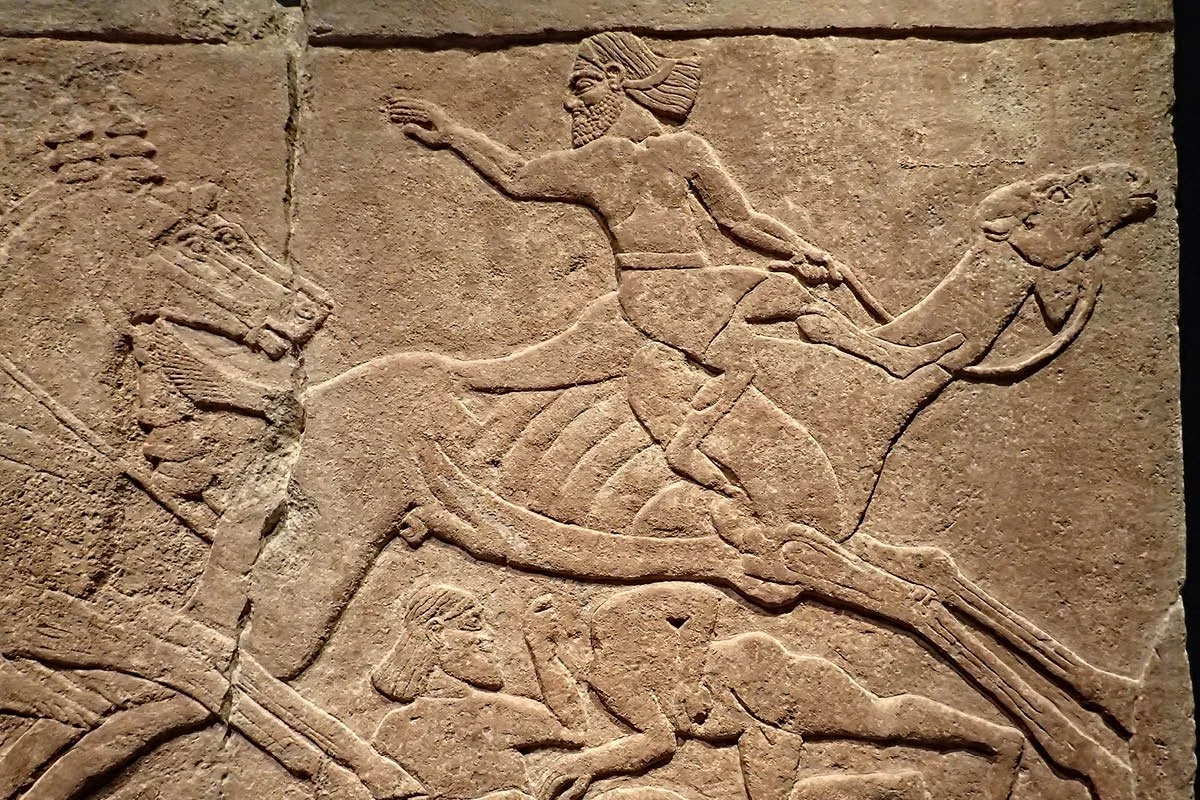

Assyrian soldiers confront a camel rider in this detailed relief from the palace of Tiglath-pileser III.

If walls could talk, Assyrian palace walls would roar. Assyrian reliefs lined long corridors with hunts, sieges, and quiet court scenes that taught visitors how power looked and felt. The famous ones live in museums today, but they were made to be walked past in sequence. That is the key. They are stories carved in stone for moving bodies.

Start with Ashurbanipal’s lion hunts and the Dying Lioness from Nineveh, the Siege of Lachish from Sennacherib’s palace, elegant panels like Groom Leading Horses, and the court programs from Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad). We will say what each shows, where to see it, and how to read them fast. For setting, keep the North Palace of Ashurbanipal in mind.

What counts as “Assyrian relief” — palace walls, shallow carving, long stories

Are these just pretty stone pictures? They are narrative wall systems made to choreograph movement. A relief is shallow carving that stays attached to the slab. In Assyria the stone is often gypsum or alabaster. Slabs were set in long courses along corridors and rooms that led to the throne. As you walked, the story unrolled at your pace.

How do you read them? Look for registers, which are horizontal bands that organize scenes. Figures repeat in planned poses so you can compare actions as you go. Small cuneiform captions name places, kings, or episodes. Borders and ground lines act like rails that carry your eye. Nothing is random. Even the way tails curve or spears angle helps you feel motion.

Why this medium? Bas-relief keeps forms crisp and close to the wall. That makes detail legible in large rooms with shifting light. Palaces used series to do what single images cannot. Repetition builds mood. Scale builds pressure. By the time you reached a throne, you had already walked through order beating chaos.

Definition

Assyrian relief: Shallow-carved palace panel that tells a story.

Keep one idea handy. These are not independent pictures. They are episodes in a route. The corridor is part of the image.

The royal “Banquet of Ashurbanipal” relief, showing the king dining under grapevines after victory.

The icons — must-know Assyrian reliefs and where to see them

Which panels define the look? Start with the lion hunts from Nineveh. In Ashurbanipal’s Lion Hunt, released lions charge and the king meets them. You see taut muscles, flying arrows, handlers bracing nets. It is courage arranged into order. Pair it with the famous Dying Lioness, a panel where a wounded lioness drags her hind legs. The pathos is real because the carving is precise. Both are in London at the British Museum. For close reading, see Dying Lion Relief, Nineveh and the North Palace setting.

Next, the Siege of Lachish from Sennacherib’s palace. It shows ramps climbing a wall, rams battering gates, and deportees on the move. You can count the tools and the damage. It is logistics carved into bands. This set is also at the British Museum. It teaches how empires really worked, brick by brick and beam by beam.

Balance the violence with Groom Leading Horses. A quiet panel, likely from Nineveh. Halters loop neatly. Manes are braided. Hands and glances sort rank without words. It is the court’s calm face. Read it as a pause in the larger rhythm. For a focused look, see Groom Leading Horses.

Then shift to Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad) near modern Mosul. Sargon II’s new capital had processional programs that paired long relief sequences with lamassu guardians. Tribute lines, building scenes, and court receptions worked together to stage approach routes. Pieces now live in the Louvre, the Oriental Institute in Chicago, and other collections. Explore the program through Dur-Sharrukin.

Mini-FAQ

Where can I see them today? British Museum in London, Louvre in Paris, OI Chicago, The Met in New York, and the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.

Which one first? Start with the lion hunts. They teach the visual rules fast.

Remember the thread. Lion hunt canon, siege logistics, court elegance, Khorsabad program. Together they map the range.

How to read them fast — poses, tools, and tiny details

Why do these scenes feel so controlled? Because small choices guide your eye. Scale equals status. Kings are larger. Attendants are smaller. Profile for action keeps bodies readable when packed into bands. Overlapping limbs and diagonal spears create motion without breaking the surface.

Look at tools and textures. Arrow flights are carved as narrow grooves. Lion skin shows tautness with fine cross-hatched lines. Veins bulge where effort peaks. Water becomes stacked ripples. Chariots gain speed through repeating wheels. The realism is selective. Faces of kings stay calm while the world around them churns. That contrast is the message.

Captions matter. Short cuneiform notes anchor place or action so the story does not float. Borders and ground lines do even more. They are frames that are also guides. Follow them and you will not get lost. When you move from panel to panel, notice how repeated poses teach you to expect the next beat. The system makes learning automatic.

A quick practice run helps. Stand back to catch rhythm. Step close for joints, veins, and tool marks. Then step back again. You will start to hear the corridor speak.

The “Dying Lion” relief, one of the most moving scenes from Ashurbanipal’s lion hunt series.

Why they still command attention — politics, display, and museum lives

Are these only about kings? They are also about how images teach in public. Palaces staged order against chaos along routes to power. Hunts tamed wildness. Sieges showed skill and reach. Tribute lines rehearsed obedience. The viewer learned by walking. That is political pedagogy set in stone.

Craft and repetition make the lesson stick. One scene of a king with a lion is impressive. Twenty scenes become a memory you cannot shake. Series beat single images for persuasion. That is why museums often rebuild long runs of slabs. They want you to feel the rhythm again, not just admire a fragment on a wall.

These objects also have modern lives. Excavations broke rooms into crates. Shipments scattered pieces. Galleries now try to echo corridors with careful lighting and long sightlines. When you visit, look for joins, plaster fills, and old mounting holes. Those marks are part of the story too. For a different palace program and threshold choreography, cross-check Dur-Sharrukin.

Conclusion

The short list opens a big door. Start with Ashurbanipal’s lion hunts, the Dying Lioness, the Siege of Lachish, the calm Groom Leading Horses, and the court sequences at Khorsabad. You will see how shallow carving, long sequences, and precise detail make authority feel inevitable. If you want to go deeper, read our Dying Lion Relief, Groom Leading Horses, the North Palace of Ashurbanipal, and Dur-Sharrukin. Then circle back to the rest of the Mesopotamia cluster.

Sources and Further Reading

British Museum — “Relief: Siege of Lachish (Sennacherib)” (n.d.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art — “The Assyrian Sculpture Court” (2022)

Musée du Louvre — “The Palace of Sargon II – The Cour Khorsabad” (n.d.)

Ministère de la Culture (France) — “Executing the Reliefs | Khorsabad” (n.d.)

Winter — “Royal Rhetoric and the Development of Historical Narrative in Neo-Assyrian Reliefs” (1981)

Watanabe — “The ‘Continuous Style’ in the Narrative Scheme of Assurbanipal’s Reliefs” (2004)

Ataç — “Visual Formula and Meaning in Neo-Assyrian Relief Sculpture” (2006)

You may also like

-

January 2026

6

- Jan 6, 2026 Greek Patterns: Meanders, Waves and Palmettes in a Nutshell Jan 6, 2026

- Jan 5, 2026 What Is the Archaic Smile? Why Greek Statues Seem to Grin Jan 5, 2026

- Jan 4, 2026 What Is a Kouros Statue? Quick Guide to Archaic Greek Youths Jan 4, 2026

- Jan 3, 2026 What Is an Amphora Vase? A Quick Guide to This Greek Icon Jan 3, 2026

- Jan 2, 2026 Doric Column: The Simplest Greek Order in Plain Language Jan 2, 2026

- Jan 1, 2026 Athena Symbols in Art: Owls, Olive Trees and the Aegis Jan 1, 2026

-

December 2025

34

- Dec 31, 2025 Greek God Statues: How the Gods Looked in Ancient Greek Art Dec 31, 2025

- Dec 30, 2025 Ancient Greek Religion: Temples, Sacrifices and Belief Dec 30, 2025

- Dec 29, 2025 Peplos Kore: Color and Identity on the Athenian Acropolis Dec 29, 2025

- Dec 28, 2025 Anavysos Kouros: A Fallen Warrior Between Life and Stone Dec 28, 2025

- Dec 27, 2025 Greek Key Pattern: Why the Meander Border Is Everywhere Dec 27, 2025

- Dec 26, 2025 Greek Paintings: Frescoes, Panels and Fragments Explained Dec 26, 2025

- Dec 25, 2025 Ancient Greek Paintings: The Few Images That Survived Dec 25, 2025

- Dec 24, 2025 Greek Black-Figure Pottery: How Greeks Painted in Silhouette Dec 24, 2025

- Dec 23, 2025 Greek Vases: Shapes, Names and How the Greeks Used Them Dec 23, 2025

- Dec 22, 2025 Greek Pottery: How Everyday Vases Became Story on Surface Dec 22, 2025

- Dec 21, 2025 Ionic Columns: How They Differ from Doric and Corinthian Dec 21, 2025

- Dec 20, 2025 Types of Columns: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian for Beginners Dec 20, 2025

- Dec 19, 2025 Ancient Greek Fashion: What People Actually Wore Every Day Dec 19, 2025

- Dec 18, 2025 Ancient Greek Houses: How People Lived Behind the Temples Dec 18, 2025

- Dec 17, 2025 Ancient Greek Map: Main Ancient Cities and Sanctuaries Dec 17, 2025

- Dec 16, 2025 Ancient Greek City-States: How the Polis Shaped Art Dec 16, 2025

- Dec 15, 2025 Ancient Greek Structures: Temples, Theatres and City Walls Dec 15, 2025

- Dec 14, 2025 Greek Architecture: Columns, Temples and Theatres Explained Dec 14, 2025

- Dec 13, 2025 Ancient Greek Sculpture: From Archaic Smiles to Classical Calm Dec 13, 2025

- Dec 12, 2025 Ancient Greek Art: A Guide from Geometric to Hellenistic Style Dec 12, 2025

- Dec 11, 2025 Archaic Period in Greek Art: Geometric Schemes and Full Figures Dec 11, 2025

- Dec 10, 2025 Geometric Art in Greece: Lines, Patterns and Tiny Horses Dec 10, 2025

- Dec 9, 2025 Greek Temples: How the Ancient Greeks Built for Their Gods Dec 9, 2025

- Dec 8, 2025 Archaic Greek Sculpture: Kouroi, Korai and the First Art Forms Dec 8, 2025

- Dec 7, 2025 Linear A and Linear B: The Scripts of the Aegean Dec 7, 2025

- Dec 6, 2025 Cyclopean Masonry in Two Minutes Dec 6, 2025

- Dec 5, 2025 What Is a Megaron? Dec 5, 2025

- Dec 5, 2025 Theseus and Ariadne: How a Bronze Age Story Survives in Greek and Modern Art Dec 5, 2025

- Dec 4, 2025 From Minoans to Mycenaeans: What Changes in Art and Power? Dec 4, 2025

- Dec 3, 2025 The Lion Gate at Mycenae: Architecture, Symbol and Power Dec 3, 2025

- Dec 3, 2025 Mycenaean Architecture: Megaron, Citadel and Cyclopean Walls Dec 3, 2025

- Dec 2, 2025 Who Were the Mycenaeans? Fortress-Cities and Warrior Kings Dec 2, 2025

- Dec 1, 2025 Minoan Wall Paintings: Bulls, Dancers and Island Landscapes Dec 1, 2025

- Dec 1, 2025 Religion in Minoan Crete: Goddesses, Horns and Sacred Peaks Dec 1, 2025

-

November 2025

36

- Nov 30, 2025 The Labyrinth and the Minotaur: From Knossos to Later Greek Art Nov 30, 2025

- Nov 30, 2025 Bull-Leaping Fresco: Sport, Ritual or Propaganda? Nov 30, 2025

- Nov 30, 2025 How Minoan Palaces Worked: Knossos, Phaistos and the “Labyrinth” Idea Nov 30, 2025

- Nov 30, 2025 Who Were the Minoans? Crete, Palaces and the First Thalassocracy Nov 30, 2025

- Nov 29, 2025 Daily Life in the Cyclades: Homes, Graves and Sea Routes Nov 29, 2025

- Nov 28, 2025 The Plank Idols: How to Read a Cycladic Figure Nov 28, 2025

- Nov 27, 2025 Why Are Cycladic Idols So “Modern”? Minimalism Before Modern Art Nov 27, 2025

- Nov 26, 2025 What Is Cycladic Art? Marble Idols, Graves and Meaning Nov 26, 2025

- Nov 25, 2025 Bronze Age Ancient Greece: From Cycladic to Mycenaean Art Nov 25, 2025

- Nov 24, 2025 Aegean Art Before Greece: Cycladic, Crete and Mycenae Explained Nov 24, 2025

- Nov 16, 2025 Eye of Ra vs Eye of Horus: 5 Key Differences Nov 16, 2025

- Nov 15, 2025 Mummification Meaning: purpose, symbols, tools Nov 15, 2025

- Nov 14, 2025 Memphis: Site Dossier and Early Capital Nov 14, 2025

- Nov 14, 2025 The First Dynasty of Egypt: a Complete Framework Nov 14, 2025

- Nov 13, 2025 How Ancient Egyptian Architecture Influenced Greece and Rome Nov 13, 2025

- Nov 12, 2025 7 Facts That Make Tutankhamun’s Mask a Masterpiece Nov 12, 2025

- Nov 12, 2025 A Visual Framework for Studying Egyptian Sculptures Nov 12, 2025

- Nov 11, 2025 Inside the Pyramids of Giza: chambers explained Nov 11, 2025

- Nov 10, 2025 Philae Temple: Isis Sanctuary on the Nile Nov 10, 2025

- Nov 10, 2025 Why Ancient Egyptian Houses Were Surprisingly Advanced Nov 10, 2025

- Nov 9, 2025 5 Hidden Details in the Temple of Hathor Stairs? Nov 9, 2025

- Nov 9, 2025 What Happened to the Great City of Memphis? Nov 9, 2025

- Nov 8, 2025 Why Did Egyptians Build a Pyramid Inside a Pyramid? Nov 8, 2025

- Nov 7, 2025 5 Things to Know Before Visiting Edfu Temple Nov 7, 2025

- Nov 7, 2025 Why Egyptian Wall Paintings Still Dazzle Historians Nov 7, 2025

- Nov 6, 2025 Ancient Egyptian Art and Culture: a Beginner’s Guide Nov 6, 2025

- Nov 5, 2025 7 Mysteries Hidden in the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut Nov 5, 2025

- Nov 5, 2025 Top 5 Largest Egyptian Statues: Names and Places Nov 5, 2025

- Nov 3, 2025 How Was the Pyramid of Giza Constructed Without Modern Tools? Nov 3, 2025

- Nov 3, 2025 Is Abu Simbel Egypt’s Most Impressive Temple? Nov 3, 2025

- Nov 3, 2025 What Does the Map of Ancient Egypt Really Tell Us? Nov 3, 2025

- Nov 2, 2025 Lamassu Pair, Khorsabad: Why five legs? Nov 2, 2025

- Nov 2, 2025 Ishtar Gate Lion Panel: Why one lion mattered? Nov 2, 2025

- Nov 2, 2025 Why do Sumerian votive statues have big eyes? Nov 2, 2025

- Nov 1, 2025 Dur-Sharrukin: Why build a new capital? Nov 1, 2025

- Nov 1, 2025 Standard of Ur: War and Peace in Inlay Nov 1, 2025

-

October 2025

32

- Oct 31, 2025 Dying Lion Relief, Nineveh: Why so moving? Oct 31, 2025

- Oct 31, 2025 Did the Hanging Gardens of Babylon exist? Oct 31, 2025

- Oct 30, 2025 Groom Leading Horses: What does it depict? Oct 30, 2025

- Oct 30, 2025 How did the first cities form in Mesopotamia? Oct 30, 2025

- Oct 29, 2025 What was Etemenanki, the Tower of Babel? Oct 29, 2025

- Oct 29, 2025 Standard of Ur: What do War and Peace show? Oct 29, 2025

- Oct 28, 2025 Foundation Figure with Basket: What is the ritual? Oct 28, 2025

- Oct 28, 2025 Mask of Warka (Uruk Head): The First Face Oct 28, 2025

- Oct 27, 2025 Eannatum Votive Statuette: Why hands clasped? Oct 27, 2025

- Oct 27, 2025 What are the famous Assyrian reliefs? Oct 27, 2025

- Oct 26, 2025 Gudea Statue: Why use hard diorite? Oct 26, 2025

- Oct 26, 2025 Bas-relief vs high relief: what’s the difference? Oct 26, 2025

- Oct 25, 2025 Ishtar Gate’s Striding Lion: Power in Blue Oct 25, 2025

- Oct 25, 2025 Vulture Stele: What battle and gods are shown? Oct 25, 2025

- Oct 24, 2025 What does the Stele of Hammurabi say? Oct 24, 2025

- Oct 24, 2025 Temple of Inanna, Uruk: What remains today? Oct 24, 2025

- Oct 23, 2025 Etemenanki: What did it look like? Oct 23, 2025

- Oct 23, 2025 What is Mesopotamian art and architecture? Oct 23, 2025

- Oct 22, 2025 Why is the Ishtar Gate so blue? Oct 22, 2025

- Oct 22, 2025 Ishtar Gate: Which animals and why? Oct 22, 2025

- Oct 21, 2025 Stele of Hammurabi: What does it say and show? Oct 21, 2025

- Oct 21, 2025 Lamassu of Khorsabad: The Five-Leg Illusion Oct 21, 2025

- Oct 20, 2025 Ziggurat of Ur: What makes it unique? Oct 20, 2025

- Oct 20, 2025 What is a ziggurat in Mesopotamia? Oct 20, 2025

- Oct 13, 2025 Su Nuraxi, Barumini: A Quick Prehistory Guide Oct 13, 2025

- Oct 12, 2025 Nuraghi of Sardinia: Bronze Age Towers Explained Oct 12, 2025

- Oct 10, 2025 Building With Earth, Wood, and Bone in Prehistory Oct 10, 2025

- Oct 8, 2025 Megaliths Explained: Menhirs, Dolmens, Stone Circles Oct 8, 2025

- Oct 6, 2025 Homes Before Houses: Huts, Pit Houses, Longhouses Oct 6, 2025

- Oct 5, 2025 Prehistoric Architecture: From Shelter to Symbol Oct 5, 2025

- Oct 3, 2025 Venus of Willendorf: 10 Fast Facts and Myths Oct 3, 2025

- Oct 1, 2025 Hand Stencils in Rock Art: What, How, and Why Oct 1, 2025

-

September 2025

5

- Sep 29, 2025 Prehistoric Sculpture: Venus Figurines to Totems Sep 29, 2025

- Sep 28, 2025 From Hands to Geometry: Reading Prehistoric Symbols Sep 28, 2025

- Sep 26, 2025 Petroglyphs vs Pictographs: The Clear Field Guide Sep 26, 2025

- Sep 24, 2025 How Rock Art Was Made: Tools, Pigments, and Fire Sep 24, 2025

- Sep 22, 2025 Rock Art: Prehistoric Marks That Changed Reality Sep 22, 2025