Linear A and Linear B: The Scripts of the Aegean

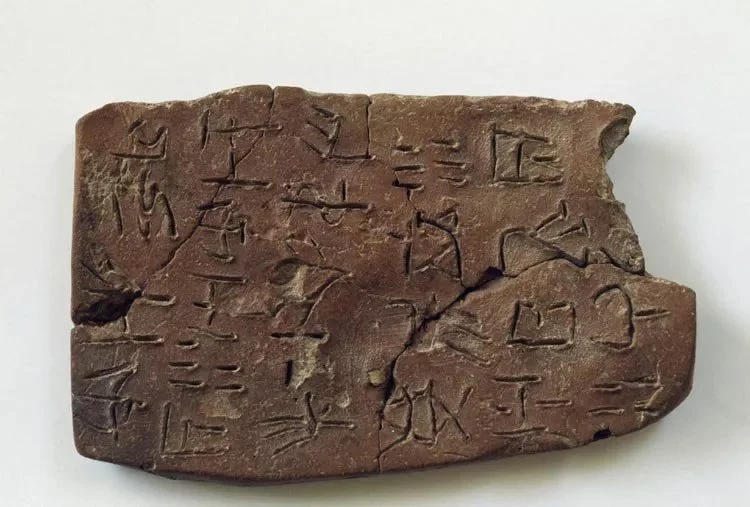

Linear B tablets like this one record palace accounts on humble clay, giving us a rare written window onto the Mycenaean world.

Imagine holding a tiny clay tablet in your hand. The surface is filled with neat, repeated signs that look almost like a code. In one case, we can read it and hear early Greek voices again. In the other, the message is still completely silent.

Those are the two main scripts of the Aegean: Linear A and Linear B. They belong to the same family, they look similar, but they behave very differently for us. One writes a language we do not understand. The other writes the earliest known form of Greek. Together, they link the palaces of Minoan civilization on Crete and the citadels of the Mycenaeans on the mainland into one administrative world.

Definition: Linear A and Linear B are Bronze Age Aegean scripts used mainly for palace administration, with Linear A still undeciphered and Linear B used to write Mycenaean Greek.

What are Linear A and Linear B, and who used them?

The simplest way to keep them straight is: Linear A is Minoan, Linear B is Mycenaean. Both are written on clay tablets and small objects in quick, incised strokes.

Linear A script appears first, around 1800–1700 BCE. It is used mainly on Crete and some Aegean islands for the palaces and shrines of Minoan civilization. Typologically, it is a logo-syllabary: a mix of syllabic signs (for sound chunks) and logograms or ideograms (for things like “wine” or “olive oil”). It records the unknown “Minoan” language and is still undeciphered today.

Linear B script comes later, around 1450 BCE, when mainland Mycenaeans take over or strongly influence Cretan palaces. They adapt Linear A to write Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested stage of Greek. Linear B is a syllabary with extra ideograms: roughly 80–90 signs for syllables plus over 100 signs for commodities like grain, oil, animals and textiles. Tablets written in Linear B have been found at Knossos on Crete and at mainland sites such as Pylos, Mycenae, Tiryns and Thebes.

In everyday terms, these scripts are the office tools of the palaces. Scribes wrote on damp clay tablets with a stylus, then dried them in the sun. When a palace burned, the heat fired the tablets, accidentally preserving thousands of short records. In our articles on Minoan civilization and who the Mycenaeans were, these scripts appear as the backbone of palace accounting and control. Our comparison piece on Minoans and Mycenaeans picks up exactly this handover from Linear A to Linear B as one of the key links between the two worlds.

This tiny Linear A cretula shows how Minoans used writing to seal goods and documents long before their script was ever deciphered.

What did they record, and why is Linear A still undeciphered?

Both Linear A and Linear B are spectacularly un-literary. They do not give us myths, letters or philosophy. They give us lists.

On a Linear B tablet, you might find a heading with a place or official, then a list of items and numbers: jars of oil offered to deities, numbers of sheep under a shepherd, counts of chariot parts in a workshop, or rations for workers. Museums like the British Museum and the Ashmolean hold tablets from Knossos that track offerings of oil or metal vessels in the shape of bull heads, written in this compact administrative shorthand.

Linear A tablets look similar on the surface: short, formulaic records with signs that clearly repeat in structured ways. But when scholars apply the sound values of Linear B to Linear A, the results do not produce any known language. Current work suggests that the underlying Minoan language is probably non-Indo-European, and the sign system, although related, is not simply “Linear B with different words.” That is why Linear A remains undeciphered: we lack long texts, bilingual inscriptions, and a known target language to test our guesses against.

Linear B, on the other hand, yielded in 1952 when Michael Ventris, building on Alice Kober’s groundwork, showed that it wrote an early Greek dialect. Once that key turned, thousands of tablets started talking, confirming what kind of system the Mycenaean palaces ran. Recent overviews remind us that Linear B is essentially a reorganised version of Linear A tuned to Greek needs rather than a completely new invention. Linear B is our clearest written window into the palace world you meet in who the Mycenaeans were.

So in a way, these two scripts nicely divide our experience as readers. Linear B gives us a working, if dry, voice from the Late Bronze Age. Linear A stands there on the clay, structurally understandable but linguistically opaque, reminding us that a big slice of Minoan civilization is still locked away in signs we can see but not yet hear.

Conclusion

If you zoom out, Linear A and Linear B are not just “weird old scripts.” They are how two linked cultures – the palaces of Minoan civilization and the citadels of who the Mycenaeans were – thought, counted and controlled their world. Linear A shows us a sophisticated but still mute Minoan bureaucracy. Linear B turns almost the same graphic toolkit into a readable record of early Greek administration.

For The Art Newbie journey, this glossary entry is a small but important connector: once you know that “Linear A = undeciphered Minoan script” and “Linear B = deciphered Mycenaean Greek script,” every mention of palace tablets in Aegean art and archaeology becomes less intimidating. You can also see more clearly how Minoans and Mycenaeans are part of one Aegean ecosystem, sharing not just a sea and motifs, but even the graphic skeleton of their writing.