Ancient Greek Map: Main Ancient Cities and Sanctuaries

This historical map reminds us how the Greek world was always shaped by coastlines, islands and maritime routes.

At some point, names like Athens, Sparta, Ionia and Delphi start to blur into one big mental cloud. You know they matter, you know they are somewhere around the Aegean, but you could not confidently point to them on a blank map. The result: Greek history and art feel more abstract than they really are.

In this guide, we slow everything down and treat an ancient Greek map as a tool, not a decoration. We will pin down where the main city-states, regions and sanctuaries sit, and we will keep asking a simple question: how does knowing the place change the way we understand the art that came from it? If you want a parallel big picture of how those cities worked, you can keep our overview of ancient Greek city-states open while you read.

A map turns floating names into a real landscape

A good ancient Greek map is not just a label dump. It shows coastlines, mountains and routes that explain why certain cities and sanctuaries ended up where they did. Once you see that geography, a lot of Greek art and architecture starts to make more sense.

Most maps of the Greek world highlight a few recurring zones. Mainland Greece is a patchwork of regions like Attica, Boeotia and the Peloponnese, bounded by mountain chains and cut by narrow passes. To the east lie the Aegean islands and the western coast of Asia Minor. To the west and south, arrows of colonisation reach into southern Italy, Sicily and beyond. Scholars often describe this as a fragmented, coastal world: a set of islands, peninsulas and bays that encourage seafaring and local independence rather than one big central kingdom.

If you think back to our big overview of ancient Greek art, that geography quietly explains a lot. City-states develop their own identities partly because they are separated by ridges and gulfs. At the same time, shared seas and trade routes make it easy for styles and objects to travel. A vase painted in Corinth might end up in an Etruscan grave in Italy. A sculptor trained in an island workshop might receive a commission for a sanctuary on the mainland. The map, in other words, tells you where the conversations between places are happening.

Mini-FAQ. What areas should a basic ancient Greek map include?

At minimum: mainland regions like Attica and the Peloponnese, major city-states such as Athens, Sparta, Corinth and Thebes, key sanctuaries like Delphi and Olympia, the Aegean islands, the Ionian coast of Asia Minor and main colonial zones in southern Italy and Sicily.

Once you have that skeleton, all the other articles - from Greek architecture to ancient Greek structures - slot into physical space instead of floating in textbook air.

Mainland core: Athens, Sparta, and the central sanctuaries

On most maps, mainland Greece forms the visual anchor. This is where many of the city-states you meet first are concentrated, and where several panhellenic sanctuaries sit.

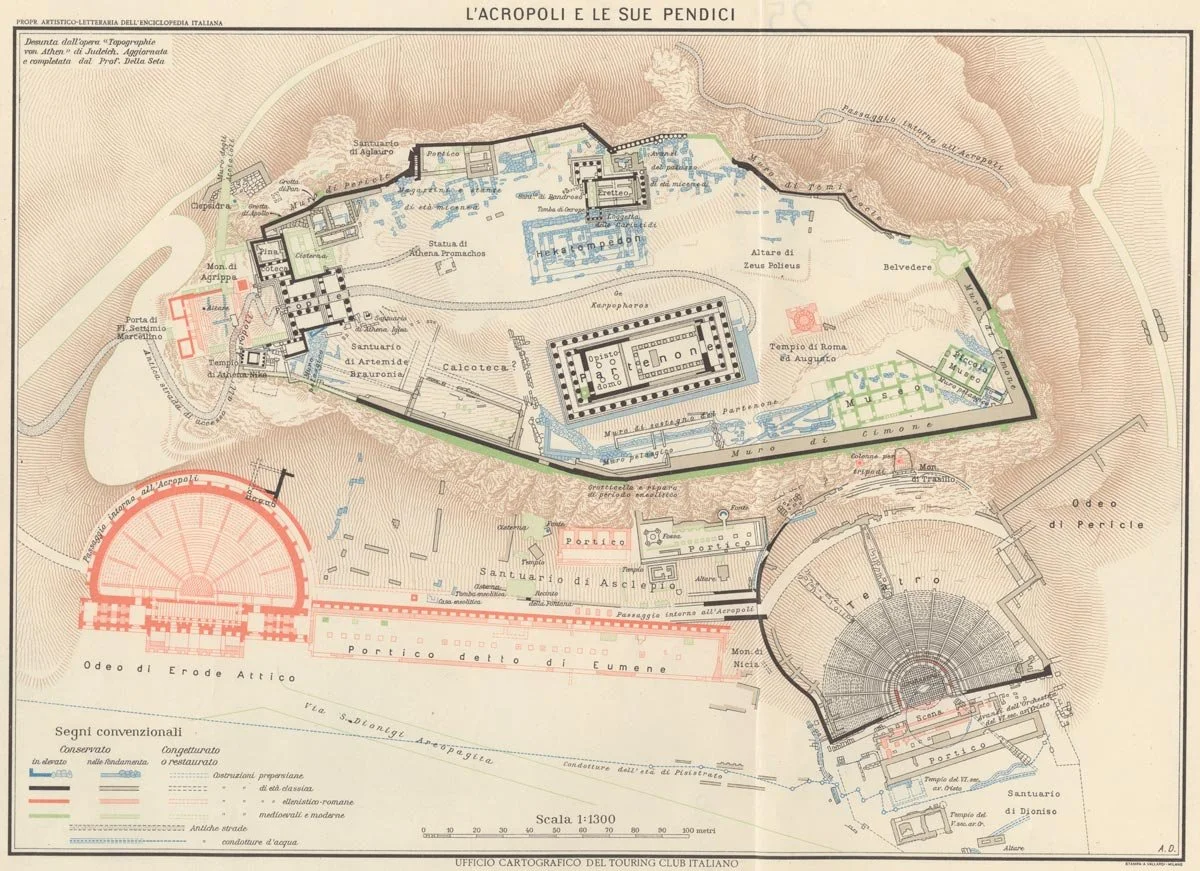

In the east, the small triangular region of Attica holds Athens. The city sits near the coast but not directly on it, with the port of Piraeus a short distance away. That combination - land routes inland, sea access outward - helps explain why Athens becomes such a powerful naval and cultural centre. When you look at the temples on the Athenian Acropolis in our article on Greek temples, you are really looking at a rocky outcrop that dominates both the plain behind it and the sea routes in front.

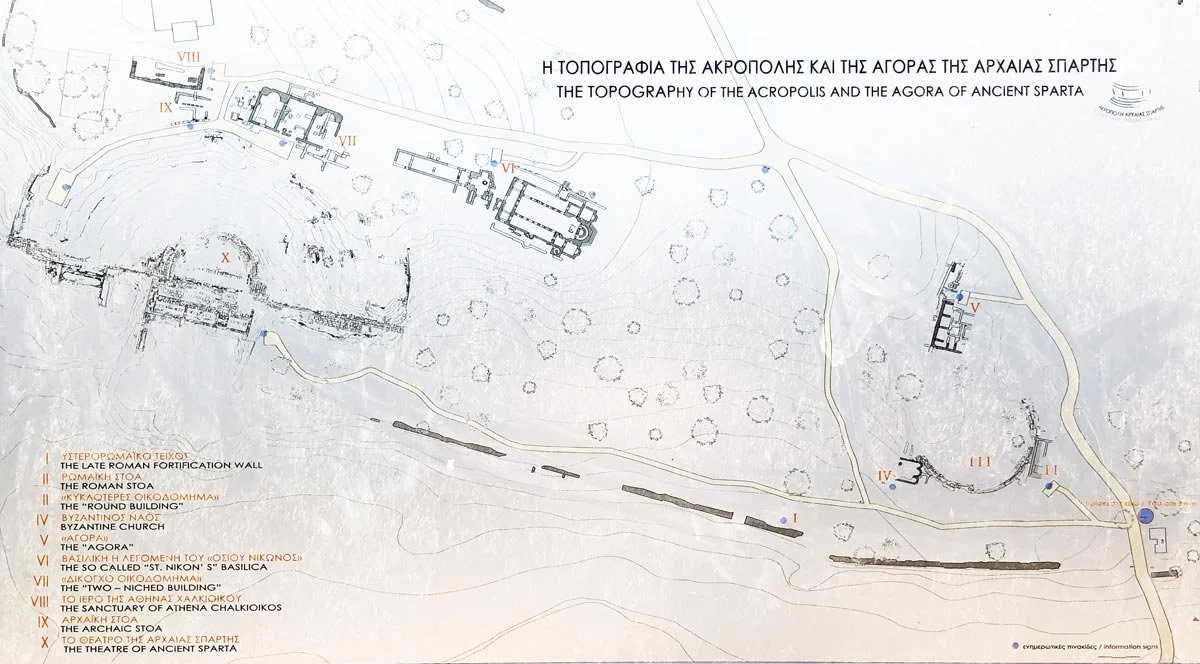

To the south, the Peloponnese is almost an island, attached to the mainland by the narrow Isthmus of Corinth. On the southeastern tip sits Sparta, in the region of Laconia, tucked inland in a fertile valley rather than perched on a harbour. That inland position, plus the strong focus on controlling the surrounding land, feeds into the more austere, militarised identity we often associate with Sparta in contrast to maritime Athens. Corinth, by contrast, sits right on the isthmus, controlling traffic between the Aegean and the western seas and becoming a major trading and pottery centre.

Between and around these cities, maps usually mark Delphi and Olympia, which belong less to a single polis and more to all Greeks. Delphi, on the slopes of Mount Parnassus in central Greece, is the sanctuary of Apollo with its famous oracle, often described as the symbolic centre or “navel” of the Greek world. Olympia, in the western Peloponnese, is the sanctuary of Zeus and the original site of the Olympic Games, a dense cluster of temples and sports structures that functioned as both religious and political theatre.

Situating these places on a map changes how we read art produced for them. A treasuries-lined path at Delphi, for example, starts to look like a physical scoreboard of city-state rivalry once you realise how many different regions had to send dedications up into that narrow mountain valley. Sculpture and temple design at Olympia become part of a broader story about travel, games and the desire to impress a panhellenic audience with both athletic skill and artistic splendour. This is where ancient Greek religion, politics and art meet in very concrete locations.

Historical Touring Club Italiano map reconstructing the Acropolis of Athens and its slopes, with major temples and theatres carefully labeled.

Seas, islands and colonies: stretching the Greek world

If the mainland is the spine, the Aegean and the wider Mediterranean are the arms. A good ancient Greek map always includes the Cycladic and Dodecanese islands, Crete to the south, and the strip of coast in western Asia Minor where cities like Miletus and Ephesus sit. By the Archaic period, Greek communities are also scattered across southern Italy and Sicily, parts of the Black Sea coast and even further west.

This seaborne expansion matters a lot for art. From an early stage, Aegean cultures like the Minoans and Mycenaeans are already using palatial spaces and wall paintings to stage movement, ritual and power. Our article on what a megaron is follows that rectangular hall form, while our piece on Minoan bull-leaping scenes explores how those island palaces used images of acrobats, animals and architecture together. Later Greek temple plans and sanctuary layouts often echo and transform those earlier spatial ideas.

On the map, you can trace how island and coastal cities become hubs for style exchange. Ionia - the band of Greek cities on the western coast of modern Turkey - is where we see early experiments in monumental architecture, certain sculptural styles and philosophical schools. Southern Italian and Sicilian colonies, sometimes called Magna Graecia, develop their own temple clusters and pottery workshops while staying plugged into wider Greek networks. A map that marks these sites helps you see why an “Athenian” style vase might turn up in a grave in Sicily, or why a certain temple detail appears both on a mainland site and an island sanctuary.

This wider geography also explains why maps of ancient Greek cities often look surprisingly scattered. For a modern viewer used to thinking of Greece as one country, it can be disorienting to realise that Greek sanctuaries and city foundations extend across modern national borders: parts of Italy, Turkey, Cyprus and beyond. Once you see that on a map, the world of Greek art and myth starts to feel more like an archipelago of related places than a single compact homeland.

Information board mapping the acropolis and agora of ancient Sparta, a guide to how sanctuaries, stoas and theatre fit into the landscape.

Mapping sanctuaries, houses and everyday routes

An ancient Greek map is not only about famous cities and panhellenic sanctuaries. It also invites us to imagine smaller scales: neighbourhoods, roads, sightlines. Here, the map connects naturally to the built kit we explored in ancient Greek structures.

Within city walls, houses cluster along streets that often follow terrain or older paths. Our guide to ancient Greek houses focuses on the typical courtyard plan, but a map lets you zoom out and see patterns: how domestic districts sit between the acropolis and the harbour, how main roads link gates to the agora or to an extra-mural sanctuary. When you place a painted vase or a small household shrine in that context, you are no longer looking at an isolated object but at something that once moved through streets and sat inside a very specific urban pocket.

On a regional scale, you can use the map to track festival routes and pilgrimage paths. Processions might climb from the city centre to an acropolis, or travel several kilometres to a rural sanctuary. Knowing that Delphi is perched on a steep slope, or that Olympia sits in a river valley, helps you imagine how worshippers experienced the approach: the bend in the road where the first temple appears, the sound of a river or sea, the line of treasuries that suddenly comes into view. Those topographical details feed directly into how sanctuaries were designed and decorated.

Finally, mapping sanctuaries across the Greek world helps make sense of shared artistic languages. When you see similar column types, sculptural themes or altar forms cropping up from Asia Minor to Sicily, the map reminds you that artisans, priests and patrons travelled. Styles radiated out from certain centres, and local workshops adapted them. That is why understanding where a site sits - on a sea route, at a crossroads, in an inland valley - is essential for reading the art it produced.

Conclusion

In the end, an ancient Greek map is less about memorising dots and more about gaining spatial intuition. Once Athens, Sparta, Delphi, Olympia, Ionia and Magna Graecia have clear positions in your mind, Greek art and architecture stop feeling like a random slideshow. Temple programmes, city plans, sculpture commissions, even myth cycles start to line up with coastlines, passes and harbours.

For me, the biggest shift is that geography turns art into a kind of conversation across space. A treasury at Delphi is no longer just a nice building, but the voice of a faraway city speaking in stone on a mountain in central Greece. A temple in Sicily is not an outlier, but part of a Greek colonising wave that carries column types and cult images across the sea. A simple courtyard house becomes one unit in a dense urban fabric squeezed between walls, hills and the route to a local shrine. Connecting this article with our guides to ancient Greek city-states, Greek architecture and ancient Greek religion lets you keep layering that spatial awareness over everything else you learn.

Next time you see a map at the start of a chapter, it might be worth pausing for a minute instead of flipping past. Trace one festival path, one sea route, one line of city walls. Imagine the artworks and buildings from other articles sitting along that line. In that moment, you are doing exactly what this series is about: turning floating names into places you can walk through in your head.