From Minoans to Mycenaeans: What Changes in Art and Power?

The so-called Mask of Agamemnon shows how thin hammered gold was used to honour elite dead and later fed the legend of Homeric kings.

Imagine walking two different Bronze Age “capitals” in the Aegean.

On Crete, you enter Knossos: bright walls with painted dolphins and bulls, open courts flooded with light, staircases that turn and turn, glimpses of the sea not too far away. There are no huge city walls. The palace feels like a sprawling organism plugged into trade routes.

A few centuries later, you climb a rocky hill at Mycenae. Here, massive stone walls press in on you. A narrow ramp leads to the Lion Gate, and somewhere above, a square hall with a central hearth anchors royal power. The sea is still there, but the architecture feels harder, more defensive, more vertical.

This is the shift from Minoans to Mycenaeans. In this explainer we will put the two worlds side by side: who they were, how their palaces and citadels worked, how their art changed, and what that tells us about power at the end of the Bronze Age. If you want a broader timeline of this period, you can pair this with our overview of Bronze Age ancient Greece, where we follow the whole arc from island graves to citadels.

Minoans and Mycenaeans share one sea, not one system

A good starting question is: how were the Minoans and Mycenaeans similar. Both belong to the Aegean Bronze Age. Both develop palatial centres, long-distance trade and rich visual cultures. Both sail the same sea, borrow motifs from Egypt and the Near East, and influence each other.

But their base camps are different. The Minoan civilization grows on the island of Crete and nearby islands from around 2000 BCE. Its key sites are palaces such as Knossos, Phaistos and Malia, each with a big central court, storage wings and surrounding town. These centres plug into trade routes that cross the eastern Mediterranean. When modern writers call Minoan Crete a thalassocracy, they mean a sea-based power whose strength flows through ships, ports and islands. You can meet this world step by step in our dedicated guide to Minoan civilization.

The Mycenaeans, by contrast, are based on mainland Greece. Their core period runs roughly 1600–1100 BCE. They build fortified palace centres at places like Mycenae, Tiryns and Pylos. These sites still trade across the sea, but they sit on hills above plains, controlling land routes, farmland and coasts. They speak an early form of Greek, recorded on clay tablets in the script called Linear B. If you want the social side of this story – kings, warriors and rich graves – we unpack it in our explainer on who the Mycenaeans were.

So Minoan vs Mycenaean is not “islands vs land” in a simple way, but more about how power is organised. Minoan centres feel like open hubs in a maritime network. Mycenaean palaces feel like hard knots in a landscape: smaller kingdoms, each with its own fortified hill and royal court. The sea connects them both, but they exploit it differently.

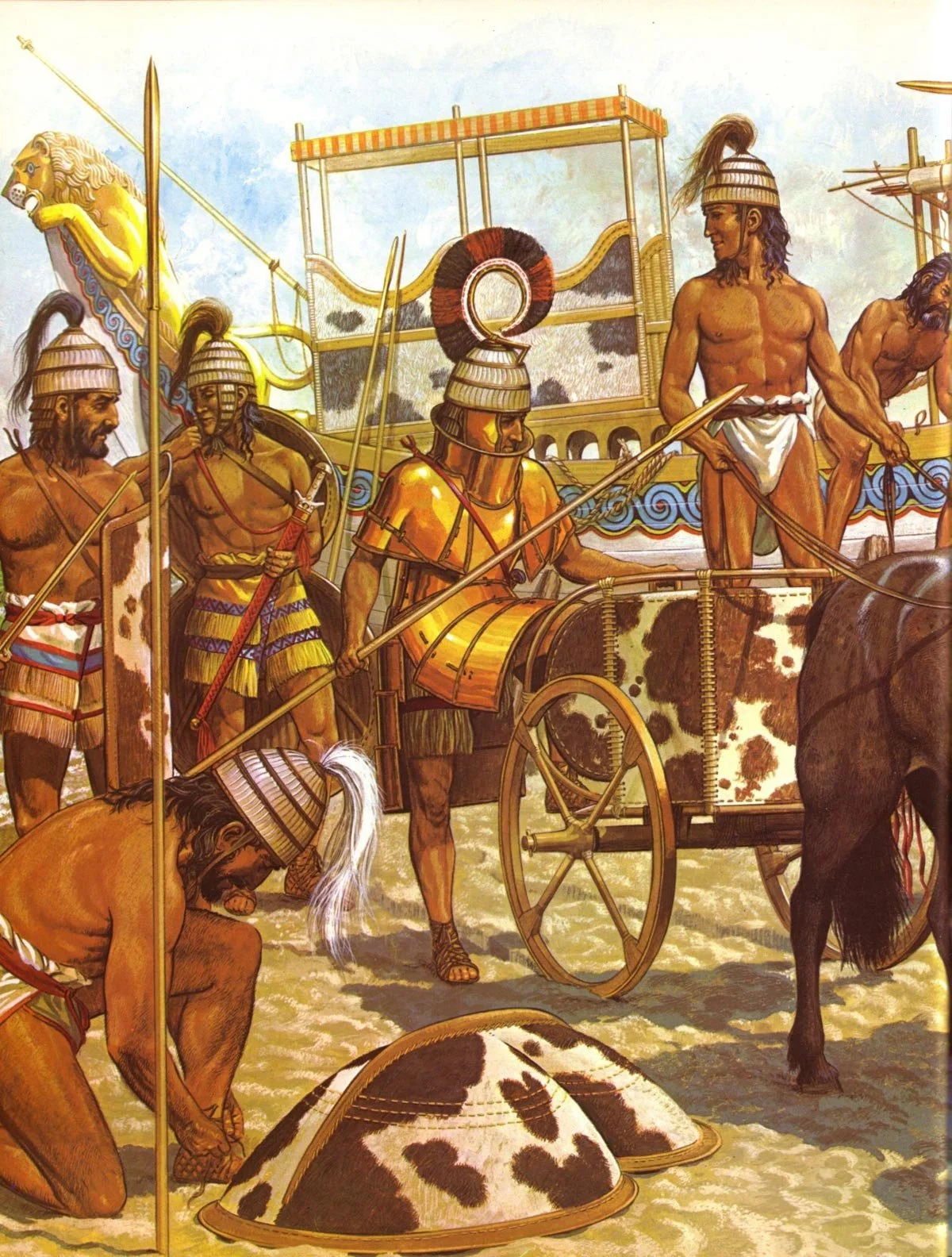

This reconstruction pulls together archaeological finds into a full bronze panoply, giving us a vivid sense of how a Late Bronze Age “hero” may have been armed.

Architecture flips from open palaces to closed citadels

One of the clearest differences between Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations sits in the floor plans. If you like drawing, this is where architecture tells the story almost on its own.

Minoan palaces on Crete are usually multi-storey complexes wrapped around a large rectangular central court. Corridors zigzag, staircases turn, light wells and pier-and-door systems let you modulate light and air. At Knossos, for example, you get long façades, terraces, ceremonial staircases and rooms like the so-called “Throne Room” with wall paintings and benches. It all feels porous: courts open to the sky, façades open to processions, town and palace bleeding into each other. Our article on Minoan frescoes follows those painted walls from bulls to island landscapes.

On the mainland, Mycenaean architecture looks and feels different. The main centres are not just big palaces; they are citadels – fortified hilltops surrounded by thick stone walls. At Mycenae and Tiryns, those walls are “Cyclopean”: built of huge limestone boulders that later Greeks will say only giants could move. Access is funneled through ramps and narrow gates like the Lion Gate at Mycenae, where relief sculpture and structure combine. Inside, the palace cluster is organised around a megaron, a rectangular great hall with a front porch, an anteroom and a central hearth. We break that hall plan down in detail in our piece on Mycenaean architecture.

In simple terms, Minoan palaces spread outward, with courts and halls woven into the town. Mycenaean citadels pull inward and upward, wrapping storage, archives and halls in defensive stone and staging a climb toward the ruler’s megaron. You can still find open courts and staircases in Mycenaean sites, but they sit inside a very different shell. Architecture tells us that threats, or at least the fear of threats, are now part of how these communities imagine their world.

Myth vs Fact

Myth: Minoans were peaceful artists and traders, Mycenaeans were only warlike fortress builders.

Fact: Minoans also show weapons and power symbols, and Mycenaeans also engage in trade and ritual; the real difference lies in how strongly defense and hierarchy are built into Mycenaean citadels.

Art shifts from fluid nature scenes to tighter, warrior-focused images

If you stand in front of Minoan frescoes on Crete, the first impression is usually movement. Bulls charging and leaping, human figures twisting in athletic poses, rocky coasts with plants and birds, multi-coloured fish in the sea. Backgrounds often dissolve into flowing color and pattern. Dress is rich and patterned, but faces can feel almost anonymous, caught mid-gesture.

In pottery, too, Minoan artists love marine and floral motifs: octopuses that stretch across the pot, shells, seaweed, swirling spirals. The overall effect is light and rhythmic. Power is still there – bulls, processions, possible gods and goddesses – but the framing is often natural and dynamic.

Mycenaean art talks in a slightly different accent. It borrows a lot from Minoan style, especially early on, but tightens and redirects it. Palace frescoes at Pylos or Mycenae still show processions and patterned borders, yet themes like warriors, chariots and shields appear more often. Pottery decoration becomes more symmetrical and controlled: bands, rosettes, stylised animals, and scenes of hunting or battle. Many scholars point out that Mycenaean painters love the figure-eight shield and the chariot as repeated motifs.

This is not a clean switch from “nature” to “war”, but a shift in emphasis. Where Minoan images often stage ritual and nature together, Mycenaean images more frequently foreground ranked humans, weapons, chariots and formal processions. That fits the architecture: open courts with flowing images versus citadels whose art underlines hierarchy and control. For a deeper dive on each visual world, you can read our separate explainer on Minoan frescoes and the more warrior-centred world of who the Mycenaeans were.

Seen together, Minoan and Mycenaean art show how visual language responds to changes in politics. The same bull, ship or procession can signal slightly different things when painted on the walls of an open court at Knossos or the inner rooms of a hilltop citadel.

Scenes like this imagine Mycenaean elites as seafaring warlords, echoing the world of ships and chariots described in Homer.

Power, writing and collapse: who holds the centre, and for how long?

Underneath style and stone there is another layer: how power and writing work in the two systems.

On Crete, Minoan palaces use hieroglyphic signs and a script we call Linear A. It is written on clay tablets and sealings, mostly for accounting. We have not yet deciphered it, so we see the skeleton of the bureaucracy but not the full body of its language. What we can say is that palaces control storage and redistribution: grain, oil, textiles, metals. Religion and politics seem tightly connected, with cult rooms inside palaces and peak sanctuaries on nearby mountains.

At some point after the great destructions on Crete around the mid-second millennium BCE, a shift happens. Power at Knossos and perhaps other centres falls increasingly under Mycenaean control. A new script, Linear B, appears: visually similar to Linear A but encoding early Greek. The palatial system continues for a while in a hybrid form. Minoan-style frescoes coexist with Mycenaean-style motifs. Administration runs on Greek language written in an adapted script. Our entries on Minoan civilization and who the Mycenaeans were trace that overlap from both sides.

Then, around 1200–1100 BCE, the wider system cracks. Across the eastern Mediterranean, many palaces and cities are destroyed or abandoned. Mycenaean citadels strengthen their walls and water access, but many are eventually hit by fire and collapse. Linear B stops being used. Trade shrinks. This is the transition from the palatial world of Minoans and Mycenaeans into the simpler, more fragmented communities of the Early Iron Age. Our overview of Bronze Age ancient Greece sets this collapse in its wider regional context.

What survives is not the palaces, but memories, ruins and habits. Later Greeks will remember a great seafaring past in myths of Minos and the labyrinth, and a heroic, warlike past in stories of Mycenaean kings. They will build their own cities and temples in dialogue with those ruins, sometimes copying, sometimes reacting against them.

This bull-shaped pouring vessel shows how animal forms could turn everyday rituals of drinking and libation into something theatrical and symbolic.

Conclusion

When we line up Minoans and Mycenaeans side by side, the question is not “which is better,” but what changes in art and power when a maritime island network gives way to hilltop citadels. On Crete, we saw open palaces, flowing frescoes and a sea-facing system that embeds power in courts, rituals and routes. On the mainland, we watched citadels, megaron halls and Cyclopean walls condense that energy into fewer, harder nodes of control.

In visual terms, Minoan art leans into movement, nature and ritual scenes that feel almost weightless, even when they carry political messages. Mycenaean art, while still borrowing Minoan style, emphasises warriors, chariots, shields and ranked processions. Architecture amplifies the same shift: from dispersed, court-centred palaces to compact, defended Mycenaean architecture that makes you climb and submit to a sequence of controlled spaces.

For our larger journey through Aegean and Greek art, this comparison matters because it shows that “Greek art” does not appear out of nowhere. It grows out of experiments like Minoan palaces and Mycenaean citadels, and out of the conversations between island and mainland. If this guide helped you see those two worlds as connected but not identical – sharing one sea, but not one system – then you are ready to zoom in further on each side: wander again through Minoan civilization, climb back up to who the Mycenaeans were, or follow the thread forward into the first stone temples of Archaic Greece.

Sources and Further Reading

The Metropolitan Museum of Art — “Minoan Crete” (2002) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art — “Mycenaean Civilization” (2003) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Khan Academy / Smarthistory — “Minoan art, an introduction” (2020) (Khan Academy)

Khan Academy / Smarthistory — “Mycenaean art, an introduction” (n.d.) (Khan Academy)

World History Encyclopedia — “Minoan Civilization” (2018) (World History)

World History Encyclopedia — “Mycenaean Civilization” (2019) (World History)

James C. Wright — “Beyond the Versailles Effect: Mycenaean Greece and the Minoan World” in The Mycenaean Feast (2004) (books.openedition.org)