Aegean Art Before Greece: Cycladic, Crete and Mycenae Explained

The famous Ladies in Blue fresco from the Palace of Knossos, one of the most iconic examples of Minoan wall painting.

Picture a chain of islands and rocky coasts, all scattered around a deep blue sea. On one island, someone carves a tiny marble figure with folded arms. On another, painters cover palace walls with leaping bulls and lilies. On a headland facing the mainland, builders raise a stone gate topped by two lions.

All of this happens before classical Greece. Before the Parthenon, before red-figure vases, before the word “philosophy” exists, the Aegean is already a huge open-air workshop. In this workshop, three main cultures shape what we now call Aegean art: the Cycladic islanders, the Minoans on Crete, and the Mycenaeans on the Greek mainland.

In this guide, we will keep them separate enough to feel their personalities, but close enough to see the shared sea tying them together. We will move from small marble idols to painted palaces, from palaces to fortress-cities, and then forward to early Greece.

What is Aegean art, exactly?

Aegean art is the visual world of the Bronze Age cultures living around the Aegean Sea before classical Greece. In other words, it gathers the art of the Cycladic islands, Minoan Crete, and Mycenaean Greece, roughly between 3200 and 1100 BCE.

The label sounds neat, but the reality is messy, because “Aegean art” is a modern umbrella term. Archaeologists grouped these cultures together when they realised how much they traded, copied and influenced each other. So when we use the term here, we are talking about a network of seafaring communities, not a single empire or kingdom.

Most of what we know comes from three kinds of evidence: burials, settlements and palaces or citadels. In graves, people buried marble figurines, metal weapons, pottery and jewellery. In settlements, we find houses, shrines and workshops. In palaces and fortress-cities, we see the most ambitious architecture, frescoes and storage systems. Together they tell us how people lived, what they valued, and how they imagined their gods and rulers.

At the same time, there are big gaps. Linear A, the main Minoan script, is still undeciphered. Cycladic settlements are poorly preserved. Many early finds were removed from their original context by 19th- and early 20th-century collectors. So when we say “likely” or “probably” below, we are not hedging for style. We are admitting that Aegean art is read through fragments.

Definition: Aegean art is the Bronze Age art and architecture of the Cycladic, Minoan and Mycenaean cultures that lived around the Aegean Sea before classical Greek civilization.

Cycladic figurines: minimalist early Aegean sculpture that shaped prehistoric art.

Cycladic islands: why start with small marble figures?

Cycladic art is our quiet starting point, because it looks simple and mysterious at the same time. The Cyclades are a ring of small islands in the central Aegean. Around 3200–2000 BCE, people here carve marble vessels and figurines, and bury them in graves. These are the famous folded-arm figures: stylised human bodies standing upright, arms crossed over the chest, faces reduced to a long nose and smooth planes.

At first glance they seem “modern”, almost like works by Brancusi or Modigliani. That resemblance is not a coincidence. Early 20th-century artists saw them in collections and admired their reduction to pure form. For us, this modern echo is a trap and a gift. It helps us feel their power, but it can make us forget that these objects had a Bronze Age meaning, not a 1900s one.

Archaeologically, most Cycladic figures come from burial contexts, often placed beside the dead. Many are small enough to be held in the hand. Some have traces of paint, especially on the face. That suggests they were once more vivid than their bare marble surface today. Scholars have proposed many roles: protectors of the dead, images of ancestors, representations of deities, or even prestige goods circulating between islands. None of these explanations is secure, but all agree on one thing: the figures matter because they travel with people, both in life and in death.

Cycladic pottery and marble bowls add more clues. We see simple geometric decoration, careful stone working, and an economy that can afford to spend time on non-functional beauty. When you look at a Cycladic figurine next to a plain storage jar, you start to see a society testing what marble can do.

If you want to dive deeper into this, you can explore our dedicated guide to Cycladic art. There, we zoom in on workshops, fakes, and the problem of looting. Here, the big takeaway is that the Cyclades show us an early island world where art is already portable, compact and charged with meaning that travels.

Corinthian krater with dancers and beasts — early storytelling on Greek pottery. Athens Museum of Cycladic Art

Minoan Crete: how does a palace become a painting machine?

On Crete, Aegean art suddenly gets architectural. From around 2000 BCE, the island develops large palatial centres at places like Knossos, Phaistos and Malia. A palace here is not just a royal house; it is an administrative hub, storage complex, ritual space and performance stage all at once. Its corridors, staircases and courtyards create routes for processions and gatherings.

The walls of these palaces become huge painting surfaces. Minoan frescoes show bull-leaping acrobats, processions carrying vessels, and landscapes filled with lilies, dolphins and sea creatures. Colours are strong and flat, outlines confident, compositions dynamic. Figures often wear flounced skirts or kilts, cinched waists, long flowing hair. Even when scenes are ritual, the overall impression is lively, almost playful.

Minoan artists also experiment with luxury materials. Seal stones are carved with tiny scenes of animals, ships or deities. Metalworkers produce delicate jewellery and ceremonial daggers inlaid with hunting scenes. Potters move from simple linear patterns to “Marine Style” vases wrapped in octopus tentacles and shell motifs. Everywhere you look, the sea sneaks into the decoration.

One striking thing: early Minoan palaces do not have heavy fortification walls. That does not prove they lived in perfect peace, but it suggests they relied more on control through movement and ritual than on massive stone defences. Power is staged in painted halls, central courts and storage magazines lined with huge pithoi jars.

All of this makes Minoan Crete feel like a performance culture. Art, architecture and ritual are woven together. When you walk through a reconstruction of Knossos, you are not just seeing walls; you are retracing processional routes, glimpsing painted fragments, and sensing a society that expresses itself through spectacle.

For a closer look at how this culture worked, see our dedicated article on the Minoan civilization, where we tackle writing systems, religion and the Minotaur myth in more detail.

Mini-FAQ

Is Aegean art the same as ancient Greek art?

No. Aegean art comes earlier and belongs to different cultures, but it helps set the stage for later Greek art.

When does Aegean art start and end?

It begins around 3200 BCE with early Cycladic and Cretan communities and ends around 1100 BCE with the collapse of Mycenaean palaces.

Mycenae and the mainland: why does art turn into stone armour?

By the time we reach the Mycenaeans on the Greek mainland, the tone of Aegean art changes sharply. From around 1600 to 1100 BCE, centres like Mycenae, Tiryns and Pylos build fortified citadels on rocky hills. Their walls use enormous blocks of limestone, so large that later Greeks say they must have been built by Cyclopes.

Inside these citadels, palaces are organised around a megaron, a rectangular hall with a central hearth and throne. Columns frame the entrance, leading from forecourt to vestibule to main hall. This layout becomes important later, because the megaron plan will echo in some early Greek temples. For now, it is the stage on which rulers receive guests, perform rituals and display power.

Mycenaean art mirrors this heavier, more martial setting. In the early period, shaft graves at Mycenae contain gold masks, inlaid daggers and richly decorated cups. Later, the famous “Treasury of Atreus” and other tholos tombs use monumental corbelled domes to bury elites in dramatic underground spaces. On pottery and small objects, we see chariots, warriors, hunting scenes and spiral motifs. The Lion Gate of Mycenae shows two lions flanking a central column, a compact composition that still radiates strength.

Compared to Minoan art, Mycenaean imagery often feels tighter and more controlled. Frescoes exist, but they tend to favour ranks of warriors or stylised processions. Pottery decoration can be dense and repetitive, with formalised motifs. Where Minoan palaces open to courtyards and the landscape, Mycenaean citadels close around their cores, looking outward through controlled gates and ramps.

It is tempting to see this as a simple shift from “peaceful Minoans” to “warlike Mycenaeans”, but reality is more complex. Crete eventually falls under Mycenaean influence, and Mycenaean palaces adopt some Minoan artistic habits. To understand that tangle, we unpack the politics and archaeology in our piece on who the Mycenaeans were and in the comparative guide on Minoans and Mycenaeans.

The Minoan Bull-Leaping Fresco: ritual, risk, and color from Bronze Age Crete. Heraklion Archaeological Museum

A shared Bronze Age sea: what links Cycladic, Minoan and Mycenaean art?

Despite their differences, these three cultures share one big stage: the Aegean Sea itself. When we step back, patterns start to line up. Trade routes connect Cyprus, the Levant, Egypt and the Greek mainland. Metals, stone, textiles and ideas move on ships, and art follows those routes.

One obvious link is material choice. All three cultures value fine stone, metals and ceramics. Cycladic carvers specialise in marble. Minoan artists refine stone vessels and bronze tools. Mycenaean craftsmen produce gold work, inlaid weapons and fine pottery. The technical skills overlap, and objects sometimes move between regions as gifts or trade goods.

Another link is iconography, the shared visual language of motifs. Spirals, rosettes, marine creatures and hybrid animals circulate from island to island. Minoan artists borrow from Egypt and the Near East; Mycenaean artists borrow from Minoans. Over time, motifs become more schematic, but we can often trace a family line back to a common ancestor.

Architecture also shows echoes. Central courts in Minoan palaces may respond to open communal spaces seen in other Bronze Age cultures. Mycenaean citadels borrow some Minoan room types and decorative techniques. Even Cycladic villages, though less well known, show early experiments with compact, terrace-like housing on rough terrain.

Most importantly, all three cultures use art to negotiate power, memory and the divine. Cycladic figurines accompany the dead into the ground. Minoan frescoes turn ritual into moving image. Mycenaean gates and tombs freeze authority into stone. Art is not an optional extra; it sits at the centre of how these societies imagine themselves.

So when we speak of “ancient Aegean art”, we are really mapping a constellation of local styles linked by ships, stories and goods. The sea is the connector, the highway and sometimes the barrier when things fall apart.

The Lion Gate: monumental entrance to Mycenae’s citadel and power symbol of the Bronze Age. Via World History Encyclopedia

From Aegean art to ancient Greece: what survives?

Nothing in art history resets to zero. When Mycenaean palaces collapse around 1200–1100 BCE, the Aegean world changes dramatically, but it does not forget everything. Some threads from Cycladic, Minoan and Mycenaean art weave into later Greek culture.

Architecturally, the megaron plan of Mycenaean palaces likely informs the later layout of certain Greek temples: a rectangular cella, an entrance porch with columns, a clear axis. The exact route from palace hall to Doric temple is debated, but archaeologists see enough continuity in building habits to suspect a relationship.

In imagery, Minoan and Mycenaean motifs survive in myths and symbols. Stories about King Minos, the Minotaur and the Labyrinth keep the memory of Crete’s palaces alive, even in distorted form. Heroic tales about Agamemnon and the Trojan War echo the world of Mycenaean warriors and citadels. Later Greek artists, when they depict these myths, are indirectly responding to a Bronze Age visual world, even if they have never seen its original frescoes.

Technical skills also leave traces. Pottery traditions adapt, but wheel-made vessels, firing techniques and certain shapes continue into the so-called Greek Dark Age and beyond. Metalworking, seafaring and long-distance trade never completely vanish, although they contract and reorganise.

This is why studying Aegean art matters for understanding Bronze Age ancient Greece and what comes after. We are not just filling a preface before the “real” story starts in the Archaic period. We are watching the first long experiment in how communities around this sea build, decorate, bury and remember.

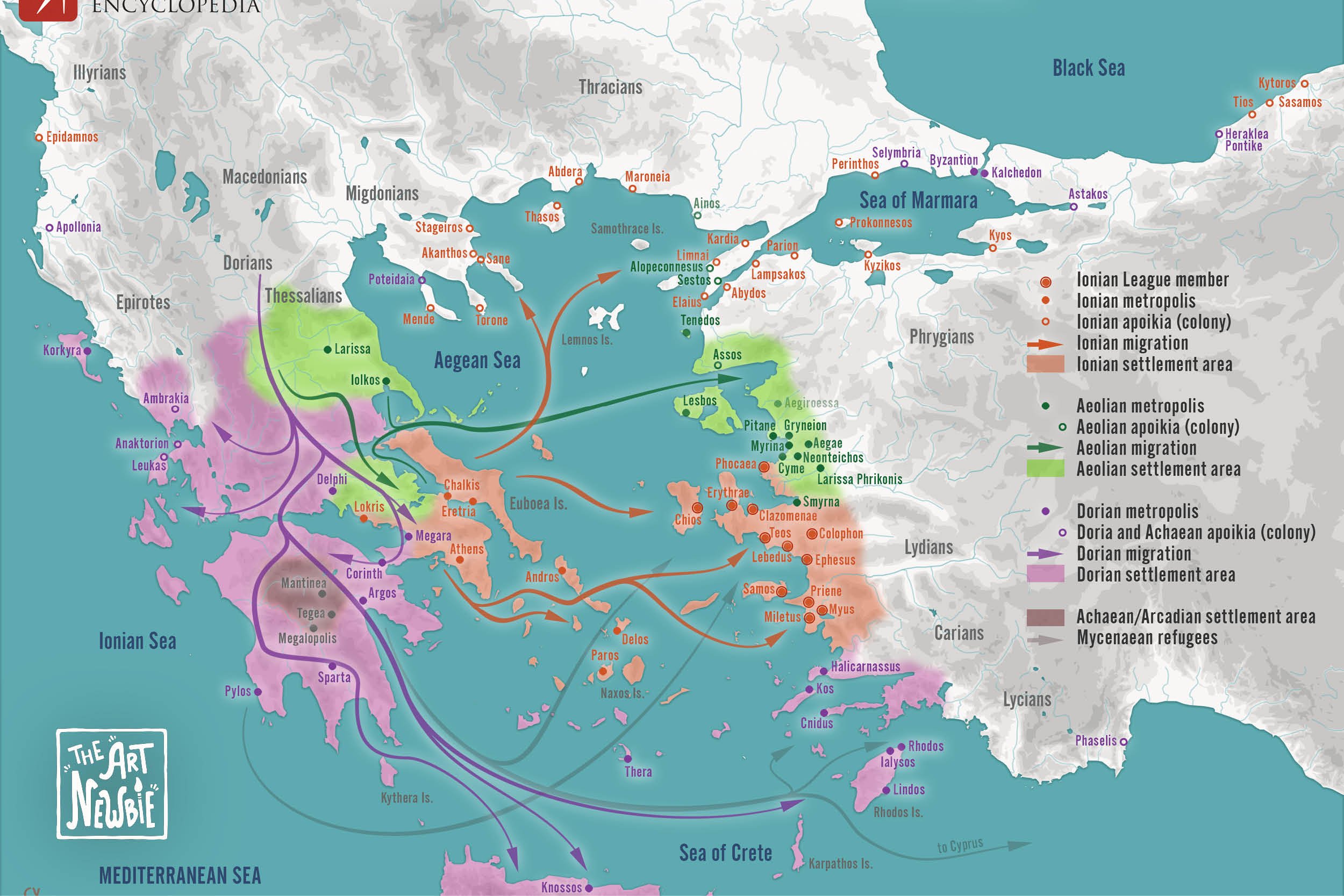

Greek migrations and colonies: how the Aegean world unfolded between 1100–600 BCE. Simeon Netchev, via World History Encyclopedia

How do we actually know all this?

Because we have no direct written histories from these cultures, our picture of Aegean art is always a reconstruction. Archaeology, science and a healthy dose of caution work together.

Excavations at sites like Akrotiri, Knossos, Mycenae and Pylos reveal buildings, wall paintings and objects in situ. Stratigraphy – the study of layers – helps date phases of construction and destruction. Pottery styles, which change over time in fairly regular ways, act as a clock for relative chronology.

Scientific methods add more detail. Radiocarbon dating can give absolute date ranges for organic materials. Isotope analysis on metals and bones reveals trade connections and migration patterns. Microscopic study of tool marks and pigments tells us how objects were made. All of this feeds into a bigger timeline that links Cycladic, Minoan and Mycenaean phases.

At the same time, there are limits. Linear A is still unread. Linear B, the Mycenaean script, mainly records inventories, offerings and administrative notes, not myths or art theory. Many objects were removed from sites decades ago without proper documentation. Some early restorations, especially at Knossos, reflect early 20th-century imagination as much as original remains.

For us as learners, the key is to keep two thoughts in mind at once. First, Aegean art is profoundly real, anchored in stones, pigments and bones. Second, every tidy diagram or textbook label is a model, not a final truth. As new digs and techniques appear, that model will shift.

Conclusion

Art historians sometimes call the Aegean the “prelude” to Greece, but that can sound like a warm-up act waiting for the main show. Walking through Cycladic graves, Minoan palaces and Mycenaean citadels, it feels more like we are already in a busy studio. Ideas about space, ritual, power and beauty are being tested in marble, pigments and stone long before the Parthenon.

If we zoom out, the Aegean in the Bronze Age becomes a laboratory for something bigger: how coastal communities turn limited resources and risky sea routes into complex visual cultures. From a tiny folded-arm figurine to a lion-guarded gate, every object is a local answer to a shared question: how do we make our world visible and memorable?

In the next steps of this journey, we will unpack each culture in more detail, and then cross the threshold into Archaic and Classical Greece. For now, if the Aegean feels less like a blank gap and more like a living workshop, this guide has done its job.