Archaic Period in Greek Art: Geometric Schemes and Full Figures

The lion mauling a bull captures the sharp energy and stylised anatomy typical of early Archaic Greek temple sculpture.

Walk into a room of Greek art that jumps from patterned vases to confident marble bodies and something feels missing in the middle. How do we get from zigzags and stick-figures to the poised athletes and calm goddesses of the Classical age? That “missing” middle is exactly what we call the Archaic period. It is the moment when geometry slowly stretches, bends and thickens into full human figures, and when wooden shrines turn into stone temples.

In this guide we treat the Archaic period like a bridge. We will pin down what years we are talking about, see how geometric schemes evolve on pottery and in sculpture, and watch temples become the new stage for carved stories. If you want to see where we are coming from, it helps to keep our explainer on geometric art in Greece open, and to know that this period leads directly into the world mapped in our overview of ancient Greek sculpture.

In art history, the Archaic period in Greek art is the phase between about 700 and 480 BCE when geometric designs give way to more naturalistic figures, stone temples and large-scale sculpture.

What Is the Archaic Period in Greek Art, Exactly?

The Archaic period is best understood as a transition zone. It sits between the patterned world of the Geometric era and the polished balance of Classical Greece. Chronologically, most scholars place it roughly from the late seventh century to the early fifth century BCE. It begins as geometric motifs loosen and figures grow more prominent, and it ends around the Persian Wars, when new political and artistic conditions in places like Athens set the stage for what we call Classical art.

The word “Archaic” is a later label, chosen by modern scholars. It can be misleading if we hear it as “primitive”. In reality, this was a period of intense experimentation. City-states were forming, trade routes widening, and artists were encountering ideas from Egypt, the Near East and older Aegean cultures. If you remember the charging acrobats from Minoan bull-leaping art, the Archaic period is when that kind of dynamic body finally returns to Greek art, this time in stone and on large painted surfaces.

Artistically, several big shifts happen at once. Potters move from pure pattern to more complex narrative scenes. Sculptors begin carving life-size stone figures, the kouroi and korai we explore in our article on Archaic Greek sculpture. Architects start translating wooden temple forms into lasting stone, laying the groundwork for the Doric and Ionic buildings you meet in our guide to the Greek temple.

Politically and socially, this is also the time when many poleis, or city-states, define themselves through shared sanctuaries, festivals and monumental building. Art is no longer just small-scale and local. It becomes a visible, durable way for communities to announce who they are and which gods they serve. When we talk about the Archaic period in Greek art, we are therefore talking about style and society together: new images for a rapidly changing world.

Mini-FAQ. What are the dates of the Archaic period in Greek art? Most surveys place it roughly between 700 and 480 BCE, with local variations and overlaps.

Terracotta roof ornament in the form of a roaring lion head, its patterned mane and faint color hinting at temple roofs.

How Do Geometric Schemes Turn Into Full Human Figures?

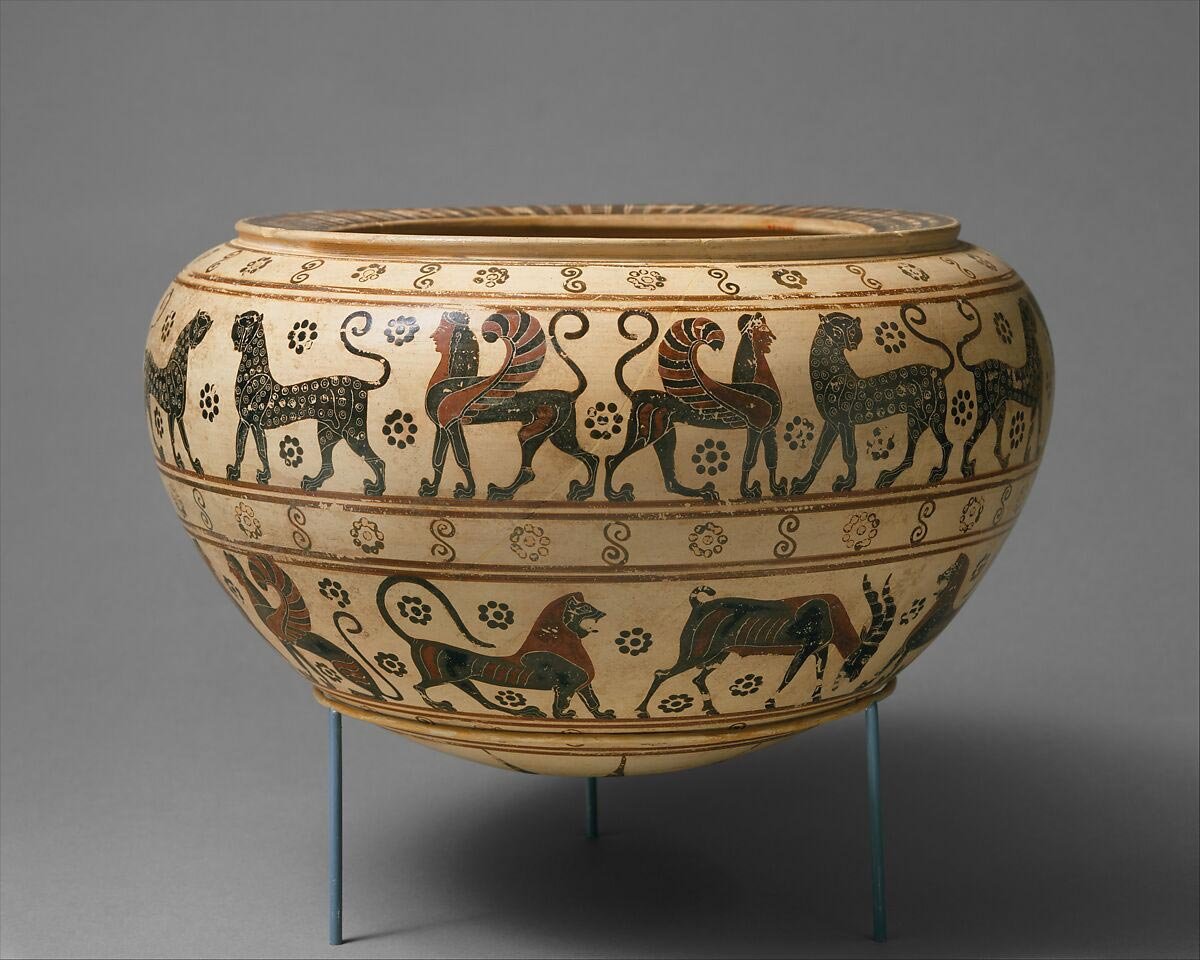

To see the Archaic period at work, it helps to start on clay. Early on, potters still love geometric order. Vases are wrapped in horizontal bands filled with meanders, triangles and other repeated motifs, just as in the Geometric period. The difference is that figures begin to claim more space. Humans and animals grow larger, more detailed and more central.

On late eighth and seventh century vases, warriors, chariots and processions push into the geometric frame. Shields get more convincing profiles, horses gain more volume, and bodies start to twist rather than stand stiffly in profile. By the time black-figure technique develops, which we explore separately in our guide to Greek black-figure pottery, the pot’s main zone becomes a stage for myth, not just pattern. Geometric schemes are still present, but they act as borders and spacers around scenes that are becoming increasingly narrative.

The same story plays out in three dimensions. Archaic sculptors inherit a love of clear structure from geometric art. You can feel it in the strict frontality and symmetry of early kouroi and korai. Bodies stand straight, limbs align with invisible axes, and the whole figure can be broken down into simple volumes. Yet within that grid, artists slowly add softness and complexity. Muscles round out, knees and hips are more believable, and drapery on korai starts to follow the body rather than just hanging as a flat curtain. We follow this journey more closely in our deep dive on Archaic Greek sculpture, from kouroi to korai.

In both pottery and sculpture, the key is that geometry does not disappear. It becomes a framework for living forms. The meander border still marches along the rim of a vase, but now it frames a wrestling match or a god’s arrival. The strict pose of a kouros still obeys a geometric scheme, but the flesh within that scheme is fuller, more responsive to gravity and movement. The Archaic period is therefore not an abrupt break from geometric art; it is geometric art learning how to host full bodies and complex stories.

Orientalizing cauldron where lions, sphinxes and grazing beasts parade in bands, mixing Greek clay with Near Eastern motifs.

How Do Temples and Architecture Change in the Archaic Period?

One of the most visible achievements of the Archaic period is the rise of stone temples. Earlier shrines built in mudbrick and wood are gradually replaced or upgraded with cut stone walls, terracotta roofs and full colonnades. This architectural shift matters because it gives sculptors and painters large, permanent surfaces to work with.

The basic temple form stabilizes: a rectangular cella for the cult statue, surrounded by columns and wrapped in an entablature with a sculpted frieze and pediments. In our dedicated guide to the Greek temple and its parts, we walk through that plan step by step. In the Archaic period, these elements are already present, though often in heavier, more experimental versions. Columns tend to be shorter and thicker. Capitals are sometimes wider. Entablatures can feel massive compared to the more refined Classical examples.

At the same time, the architectural orders we associate with later Greek buildings are taking shape. The Doric order develops in the mainland and western colonies, with its plain capitals and triglyph-metope friezes. The Ionic order grows in the eastern Aegean and Asia Minor, with its volute capitals and continuous friezes. These systems are not yet frozen rules; they are living experiments, adjusted from site to site. If you zoom out with our overview of Greek architecture across the Archaic and Classical periods, you can see how this early trial-and-error gradually stabilizes into models that later architects treat almost like sacred formulas.

Crucially, temple architecture brings sculpture and painting into a new relationship with space. Pediments and metopes demand large, clear scenes. Artists respond by arranging gods, heroes and monsters inside strict triangular and rectangular frames. The bodies they carve here are cousins of the kouroi and korai, but now they must twist, lean or crouch to fit the architecture. In this way, Archaic temples become laboratories for composing figures in complex poses, a skill that pays off dramatically in Classical building sculpture.

So when we think of the Archaic period in terms of architecture, we are really watching geometry harden into stone. The same love of proportion and pattern that once wrapped vases now organizes entire sacred precincts. Columns, steps and pediments become the large-scale equivalents of bands, lines and borders in earlier art.

Battle scene in low relief: muscular warriors grapple at close range, armor and shield packed tight into the stone field.

Why Do Smiles and Stiff Poses Matter So Much Here?

If there is one detail many visitors remember from Archaic sculpture, it is the archaic smile. Many kouroi and korai wear a small, fixed upward curve at the corners of their mouths. Combined with their frontal, almost rigid pose, this smile can look eerie or oddly charming. It also tells us a lot about what Archaic artists were trying to do.

The stiffness in these figures is not simply clumsiness. It reflects a deliberate choice to show the body in a stable, idealized way. Standing frontally with one leg forward and arms at the sides creates a clear, legible silhouette that can be recognized from a distance, whether the statue stands in a sanctuary or marks a grave. Inside that fixed scheme, sculptors slowly introduce more realistic details: a slight shift in the hips, more accurate muscle groups, a better sense of how weight rests on the legs. We are catching them mid-process, still loyal to a geometric ideal, but increasingly hungry for naturalism.

The smile itself probably does not mean “happiness” in our modern sense. Many scholars read it as a sign of vitality and blessed status, marking the figure as alive, favored or close to the divine. Technically, it is also a clever way to animate the face. A curved mouth lets the sculptor carve deeper transitions around the cheeks and chin, creating shadows and highlights that make the head feel more three-dimensional. If you are curious about how interpretations of this smile have changed, we unpack them more fully in our focused explainer on the so-called archaic smile.

Myth vs Fact

Myth: Archaic art is just stiff and “wrong” compared to Classical art.

Fact: Archaic works show a deliberate blend of geometric order and growing naturalism, and many technical solutions developed here are essential for later Classical masterpieces.

Seen this way, Archaic smiles and stiff poses stop being signs of failure. They become signatures of a moment in progress, when Greek artists are testing how far they can push stone and clay toward life without abandoning clarity and order.

Conclusion

The Archaic period in Greek art is not just a gap-filler between “before” and “after”. It is the place where we can watch Greek visual culture learn new tricks in slow motion. Patterns from geometric art do not vanish; they stretch to frame funerals and myths on vases. Simple volumes in early figures do not disappear; they fill out into kouroi and korai that stand at the threshold of full naturalism. Wooden shrines do not simply get bigger; they crystallize into stone temples that coordinate architecture, sculpture and ritual space.

If we follow that path carefully, the Archaic period starts to feel less “archaic” and more experimental, even modern in its problem-solving. Artists are working under real constraints: hard stone, limited tools, traditional expectations. Within those limits they test proportions, refine faces and try out new narrative arrangements. Later Classical works often get the spotlight, but they build directly on this century or so of trial and error. Without Archaic schemes and figures, there is no Classical perfection.

Next time you stand in front of an Archaic statue or temple fragment, try to imagine both directions at once. Look backward, and you can still sense the ghost of geometric bands and earlier Aegean bodies. Look forward, and you can almost see contrapposto and Classical calm waiting just a few small adjustments away. In that double vision, the Archaic period reveals itself for what it really is: a bridge where geometry and full human presence finally meet.