Why Are Cycladic Idols So “Modern”? Minimalism Before Modern Art

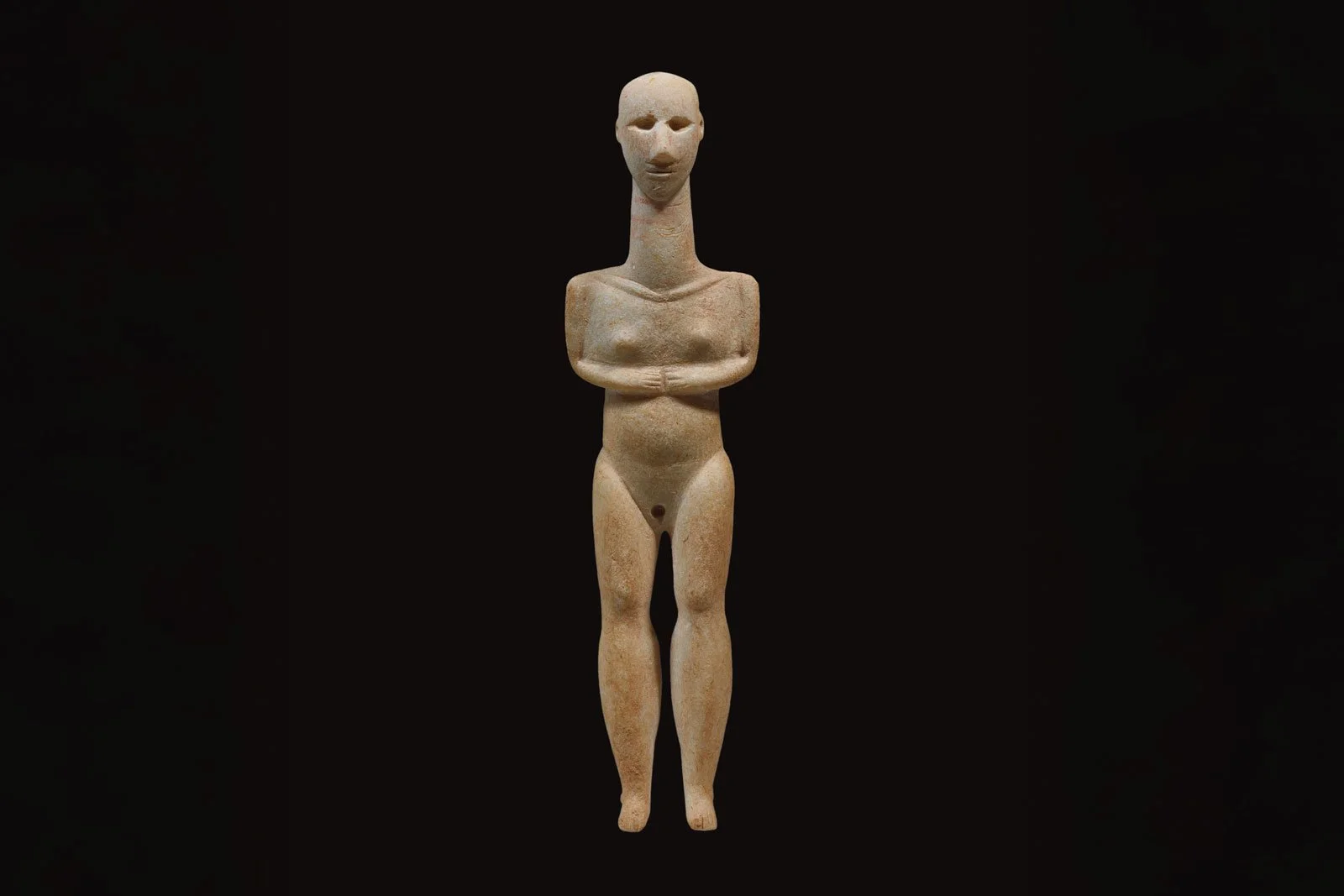

A rare Kapsala-type Cycladic figurine, with elongated proportions and an early sculptural vocabulary.

Put a classic Cycladic figure on a plinth in a white gallery. Then place a sculpture by Brancusi or a sleek design object next to it. Suddenly the 4,000-year gap shrinks. Same smooth white surface. Same stripped-down body. Same quiet pose.

So what is going on here. Why do Cycladic figures – small marble bodies from Bronze Age island graves – read like minimalist sculpture to our 21st-century eyes. And how do we talk about that without turning them into accidental modern art prototypes.

In this guide we will: define what these “idols” actually are, unpack why they feel so contemporary, and put that feeling back into their original island and grave context. If you need a broader foundation first, you can start with our explainer on Cycladic art or the overview of Aegean art, then come back here to zoom in.

Cycladic figures look “modern” because our eyes are trained by minimalism

The first piece of the puzzle is not ancient at all. It is us. Our eyes have been trained by minimalism, a twentieth century approach to art and design that strips forms down to simple shapes, flat planes and clean surfaces. Think of a single steel beam leaning in a gallery. A pure white ceramic vase. A phone designed as a rectangle with rounded corners.

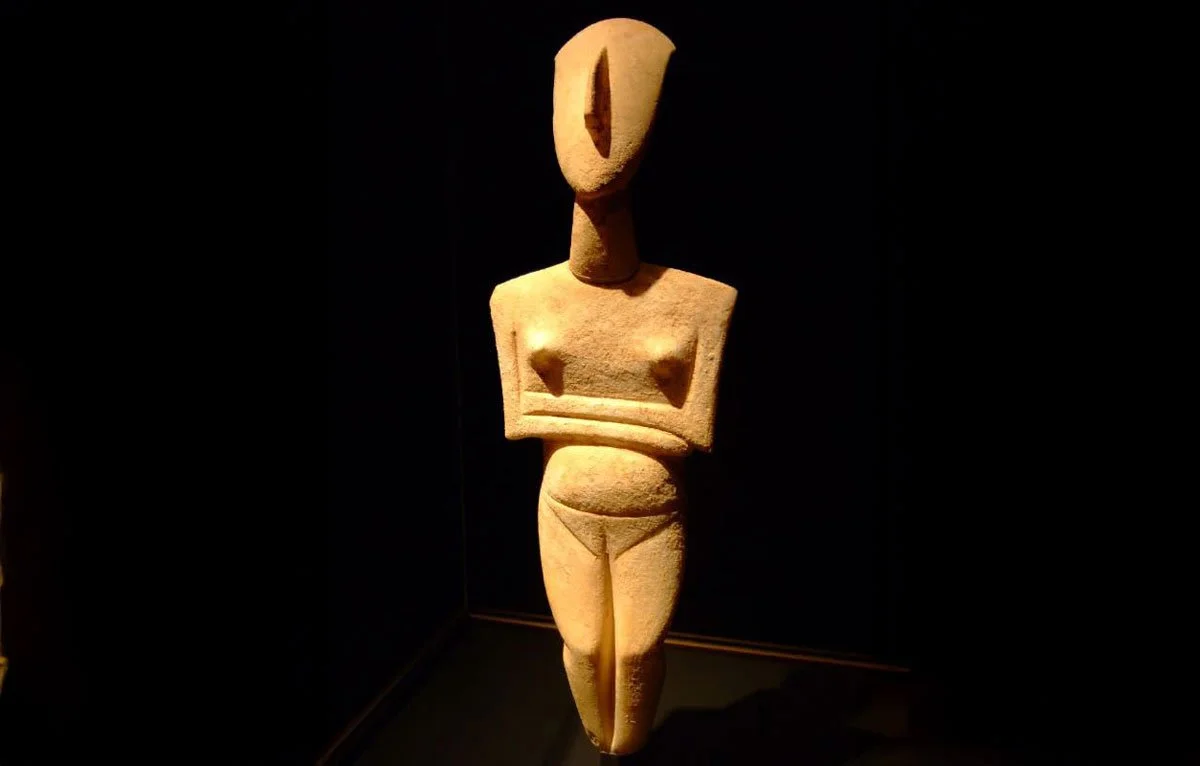

When we look at Cycladic idols, we see exactly the things minimalism has taught us to value. Bodies reduced to basic geometry. Faces without features. Marble polished into smooth planes. Arms and legs marked by fine incisions rather than fully separated volumes. The whole figure fits comfortably in the hand and in a simple outline. It feels intentional and “designed”.

That effect was already happening a century ago. In the early 1900s, European artists discovered Cycladic statuettes in private collections and museums. Sculptors like Constantin Brancusi and painters like Pablo Picasso were interested in non-classical ways of representing the human body. They saw in Cycladic art sculptures a precedent for their own experiments: a body that is recognisably human, yet highly abstract.

Museums then leaned into this connection. They placed Cycladic figures in minimal display cases, often against white or dark backgrounds, with lots of breathing space. Labels highlighted their “timeless” quality. Books on modern art reproduced them as inspirational images. All of that reinforces the idea that these are early examples of minimalist taste, that they “belong” in the same conversation as contemporary design objects.

So part of the answer is circular. Cycladic idols look modern to us because modern art and design partly learned to look from them, and because museums present them in ways that echo modern aesthetics. Our reaction is genuine, but it is also shaped by a century of curated comparisons.

A classic Cycladic marble figurine, defined by folded arms, abstracted anatomy, and clean geometric lines that shaped early Aegean visual language.

The ancient reality: Cycladic idols were made for graves and lived bodies

The second piece of the answer is older and less comfortable. In their own time, Cycladic statuettes were not design icons. They were objects that moved through real lives and deaths in the Cyclades, the ring of islands in the central Aegean Sea.

Most of the figures we know about come from graves dated roughly between 3200 and 2000 BCE. People buried their dead in stone-lined tombs and sometimes placed one or more marble figures beside the body, along with pottery and other objects. Some figurines show signs of wear, repairs or old breaks, which suggests they were handled, displayed or even passed down before burial. Others might have been made specifically for the funeral.

The context is important because it changes the emotional weight of the form. A figure with folded arms and closed legs, lying next to a person in a grave, is not just a clever abstraction of the human body. It is part of a ritual of farewell, protection or identity. It might represent a deity, an ancestor, an idealised person or something else entirely. We do not have texts from the Cyclades that explain the symbolism, so any interpretation stays a best guess. But the grave setting tells us they were not neutral decorations.

We also have to remember that what we see today is only part of the original appearance. Many Cycladic idols had painted details. Under strong light and with scientific analysis, archaeologists have found traces of red and blue pigments on faces and bodies. Eyes, hair, necklaces and patterns were once visible. Some figures even had painted “tattoos” or symbolic motifs. Their current blank faces are therefore a modern condition. For Bronze Age viewers, these figures were likely more personalised and animated.

In other words, the minimal look we love is a mix of original carving and later loss. The polished marble planes were always there. The silence of the face is not complete. Paint and context filled some of that silence with stories we can no longer fully read.

Myth vs Fact

Myth: Cycladic idols were created as early minimalist sculptures for display.

Fact: Cycladic figures were carved in the Early Bronze Age for island communities, used in life and death, and only later entered museums and modern art conversations.

The design logic: why these 4,000-year-old bodies resonate with us

Even when we respect the ancient context, there is still a design question to answer. Why do these specific proportions and shapes feel so powerful, both then and now.

If you trace the outline of a typical Cycladic figure, you get a clear, almost logo-like shape. Head, neck, shoulders, torso and legs flow into each other with very few interruptions. The widest point is often at the shoulders or hips, creating a gentle hourglass. The arms form a diagonal band across the chest, giving a subtle sense of movement inside an otherwise still pose. The feet taper to a point, which means the figure cannot stand on its own. It must lie down or be supported.

Within that basic pattern, Cycladic figures are surprisingly varied. Some are tall and slender, with long legs and narrow heads. Others are shorter or broader. Archaeologists group these types into families linked to particular islands and time periods. When you compare many examples side by side, you start to see something like a design language developing: small tweaks in angle, proportion or detail that signal different workshops and phases.

This is where the “modern” feeling becomes more than a coincidence. Cycladic sculptors worked out a set of rules for simplifying the body that is similar to what many later artists do when they move away from naturalism. They decide which lines carry the most information – the outline of the profile, the cut of the nose, the tilt of the head – and they invest their time in refining those. Everything else is reduced to a hint, a score in the marble, a shallow plane.

When modern viewers talk about these figures as “minimalist”, what they are really noticing is the confidence of that reduction. It takes skill to remove so much and still have a sculpture feel complete and human. Cycladic artists managed that centuries before anyone wrote about minimal art or industrial design.

If you want to explore the forms more closely, including high-quality images and side views, you can check our visual guide to Cycladic art figures, where we slow down and look at specific pieces one by one.

The Minoan Snake Goddess: ritual femininity and divine protection. Credits: Mark Cartwright, via World History Encyclopedia

How to enjoy Cycladic idols without time-travelling them into modern art

At this point we have two truths sitting together. Cycladic idols feel modern because they share a visual language with minimalism and modern design. They also belong to a very specific Bronze Age island world that is nothing like a twenty-first century gallery. The question is how we, as viewers and learners, hold both truths at once.

One useful move is to separate reaction from explanation. It is fine to feel that a Cycladic figure could stand next to a contemporary sculpture and still hold its own. That emotional recognition is real. The mistake comes when we flip it and say the figure is “ahead of its time” or “already modern”. Time does not work like that. What we can say instead is that both Cycladic sculptors and modern artists discovered similar solutions to simplifying the human body, under very different conditions.

Another move is to keep context in the frame. When you see a Cycladic idol in a museum, try to imagine it in its original environment. An island grave cut into rock. A small community that sees the same hills and sea every day. A funeral where someone chooses this figure, with this size and this level of polish, to accompany a specific person. The more we fill in that world, the less the object collapses into a generic symbol of “timeless minimalism”.

Finally, it helps to place these figures back into the larger story of Aegean art. Cycladic islands are one part of a wider Bronze Age world that includes palaces on Crete and citadels on the mainland. When we look at how Minoans paint walls or how Mycenaeans build gates, the Cycladic taste for compact, charged forms feels like one starting point among many, not a lonely miracle. Our broader guide to Aegean art draws those connections across the whole region.

Conclusion

Cycladic idols are easy to like and hard to pin down. Their smooth marble and folded arms offer us calm, while their missing explanations keep questions open. They stand in that interesting place where ancient craft and modern taste accidentally overlap.

For me, that is part of their charm. They remind us that certain visual choices – a tilted head, a simplified outline, a quiet pose – can speak across thousands of years, even when language and belief systems have disappeared. At the same time, they ask us to stay humble. We can borrow inspiration from their forms, but we will probably never fully recover the prayers, fears and stories that once surrounded them.

As we move deeper into Bronze Age art and then into the temples and statues of later Greece, Cycladic figures can travel with us as a small compass. They keep asking a simple, hard question: how little can you carve and still say “this is a person”. Every time we meet that question again in later periods, we will know that someone on a rocky Aegean island was already thinking about it many centuries before.