How Minoan Palaces Worked: Knossos, Phaistos and the “Labyrinth” Idea

The reconstructed north entrance with its charging bull has become an icon of Knossos, but it also reminds us how modern restorations shape our image of the ancient past.

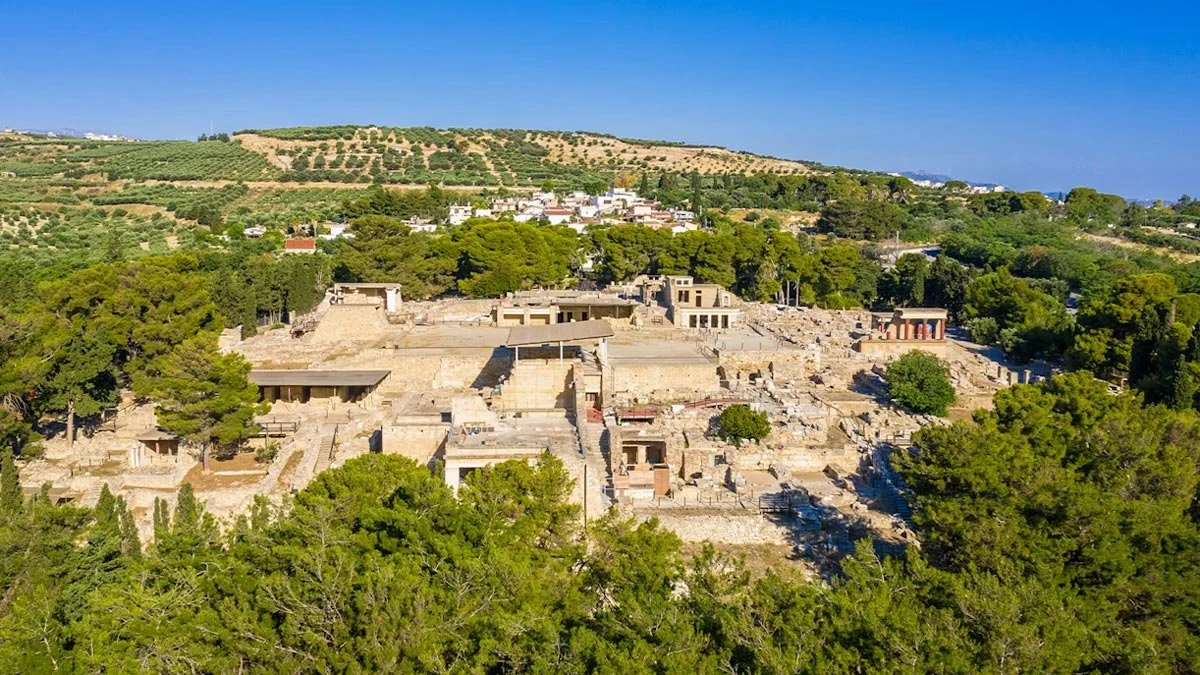

Imagine climbing a low hill on Crete and suddenly seeing it: a broad, flat complex of rooms and staircases, red columns and light wells, opening around a sunlit rectangular court. No single towering façade. No big keep. Just terraces, corridors and glimpses of colour. You step inside and very quickly lose your sense of direction.

This is what we mean when we talk about Minoan palaces. They are not castles in the medieval sense. They are administrative, ritual and residential machines built around space and movement. Later Greeks, trying to make sense of their ruins, turned that experience into the story of the Labyrinth.

In this explainer, we will walk through how these palaces were planned, how you would move through Knossos and Phaistos, and why their layouts helped feed the later “maze” idea. If you want the broader people-context around them, you can read our overview of Minoan civilization as a companion piece.

Minoan palaces are multi-purpose hubs, not just royal houses

The first thing to clear up is the word palace itself. In the Minoan context, a palace is not only where a ruler lives. It is a complex that combines storage, administration, ritual, craft and some residential space. It is closer to a town hall plus warehouse plus temple plus elite residence, all wrapped around a central courtyard.

These complexes appear on Crete around 1900 BCE, at the beginning of what archaeologists call the Old Palace or Protopalatial period. Knossos, on the north coast, is the largest and best known. Phaistos, on a terrace above the fertile Mesara plain, and Malia, near the northern shore, are equally important for understanding the pattern. Smaller palatial sites exist too, but these three give us the clearest plans.

Most palaces share a few key features. At the centre there is a rectangular court, open to the sky and large enough for gatherings, processions or performances. Around the court, wings of buildings spread out, usually two or three storeys high in their prime. Long rows of storage rooms, or magazines, hold massive jars of grain, oil and wine. Staircases climb to upper halls and balconies. Light wells bring air and daylight deep into the interior. Certain rooms repeat from palace to palace: sunken lustral basins, pillar crypts, small shrines, and suites that look like reception or residential areas.

All of this is built in local stone and mudbrick, with wooden elements and plastered surfaces. Floors in important areas are carefully paved. Columned porticoes and broad outside platforms connect the palace to its surroundings. When we look at Minoan palace architecture as a whole, what stands out is not height or mass, but complexity of circulation. The buildings are designed to guide, slow and frame movement. That is exactly what makes them feel “labyrinthine” to later visitors.

The open terraces of Phaistos, set against the Mesara plain, help us see Minoan palaces as a network of powerful centres rather than a single “capital.”

Walking Knossos: courts, corridors and controlled viewpoints

If we pick one site to experience this, it has to be Knossos. Even with modern paths and railings, walking the ruins can feel like being inside a three-dimensional diagram. The more you move, the more your sense of the whole shifts.

A typical approach in the Bronze Age likely brought you through a west court, an open paved area beside the main complex. From there, you would pass into the palace proper and head toward the central court. On the way, you might pass storage magazines on your left, with their enormous pithoi sunk into the floor, and glimpses of painted walls and columns ahead. The transition from outer to inner space is gradual. Each corridor turn, each doorway, narrows your options and focuses your attention.

Once you reach the central court, everything opens again. On one side are the formal reception and ceremonial rooms, including the so-called Throne Room with its gypsum chair and benches. On another, stairs climb toward upper halls that once had pillars, wooden ceilings and perhaps open balconies. Elsewhere, narrow passages drop down or bend out of sight. Even with a plan in hand, it is surprisingly easy to lose track of which side you came in from.

Vertical movement matters as much as horizontal. Knossos has grand staircases that connect floors in stages, encouraging you to pause on landings and look back toward the court or out to the landscape. Light wells pull sunlight deep into the interior, so you are constantly moving between brighter and darker zones. This is not accidental. It is an architecture that stages experience: controlling what you see, when you see it, and how many people can fit into each space.

Add painted walls to this, and the effect intensifies. Corridors decorated with processional scenes, dolphin friezes or patterned borders would have set a mood and a pace. Our explainer on Minoan frescoes looks closely at those images, but even at the level of plan they matter. A plain corridor guides you differently from one lined with figures carrying offerings. Knossos is, in that sense, a building you read as much as you walk.

Phaistos and Malia: same palace idea, different landscapes

Knossos is not the only palace on Crete, and that helps us see which features belong to the general Minoan palaces pattern, and which are site-specific. Phaistos and Malia are two good comparison points.

The Minoan palace of Phaistos sits above the wide Mesara plain in southern Crete. Its central court, like Knossos, is rectangular and flanked by long wings of rooms. But the approach is different. Visitors arrive via broad external steps and terraces that look out over the plain. This emphasises the link between palace and farmland. The impression is less about internal maze and more about a staged connection between interior power and the surrounding landscape. Storage magazines, ceremonial rooms and possible residential suites still exist, but the transitions from outside to inside feel clearer and more axial.

The Malia Minoan palace lies closer to the north coast, in a flatter setting. Its central court is again the anchor point, with wings around it. Here too we find magazines, workshops and special rooms that match the broader Minoan kit. At Malia, archaeologists have identified areas for metalworking and other crafts alongside more formal spaces. That mix reinforces the idea that palaces are production and redistribution centres as much as ritual stages. Goods come in from surrounding fields and harbours, are stored, processed, recorded and sent out again.

If we sketch these palaces side by side, the shared logic becomes clear. Each has:

a central court for gatherings and performances

surrounding wings with repeated room types

storage zones, likely tied to agricultural surplus and trade

circulation routes that separate public, semi-public and restricted areas

The differences lie in orientation, landscape, and how sharply movement is channelled. Knossos feels more like a sprawling organism, Phaistos like a terraced stage, Malia like a compact hub. Together, they show that Minoan palace architecture is a flexible system, adjusted to each site, not a rigid template copied without thought.

Walking through Knossos today, we experience the site as a maze of courts, stairs, and rooms that hints at how complex palace life must once have been.

From complex plans to labyrinth myth: how later Greeks reimagined these palaces

So how do we move from all of this to the “Labyrinth” idea and the Minotaur story. The short version is that classical Greeks encountered the ruins of these palaces centuries later and tried to make sense of them in their own narrative language.

By the time writers like Herodotus and later mythographers talk about Minos and the Labyrinth, the palaces of Knossos and Phaistos are long out of use. What remains are confusing foundations, fragments of painted walls and local traditions about a powerful Bronze Age past. To someone walking through the ruins, especially at Knossos, the tangle of corridors and rooms could easily feel like a maze built to contain something dangerous.

Add in bull imagery, which is everywhere in Minoan art, and the leap to a bull-monster in a maze is not so far. Frescoes of bull leaping, rhyta shaped like bull heads, and horn symbols on palace roofs all show that bulls had serious ritual importance on Crete. When later Greeks weave that into their own heroic tales, they create the Minotaur myth: a half-bull creature shut away in a complex structure, visited by a hero from the mainland. Our article on the Minotaur and the Labyrinth follows that thread in more detail.

There might also be a quieter bureaucratic side to the myth. Minoan palaces used writing, in the form of Linear A, for administration. Under later Mycenaean control, Knossos uses Linear B, an early form of Greek, to record offerings and goods. For an outsider, the combination of confusing architecture and a writing system they could not read could feel like entering a world of hidden rules and secret lists. In our explainer on Linear A and Linear B we follow how these scripts work and where they appear.

Myth vs Fact

Myth: The Labyrinth was a single underground maze designed only to imprison the Minotaur.

Fact: The “Labyrinth” idea likely grew from the complex multi-level plans of Minoan palaces, especially Knossos, and from later Greek attempts to mythologise a powerful but already ruined Bronze Age world.

Conclusion

Standing in a Minoan palace today, even as a tourist with a site map, you can feel why the word “labyrinth” stuck. Your route twists, rises, dips and opens unexpectedly. Storage rows, light wells, staircases and courts keep switching focus between goods, sky, people and landscape. It is not just a ruin; it is a kind of three-dimensional script that we are still learning to read.

For our wider journey through ancient art and architecture, Minoan palaces are useful training grounds. They show how a building can be more than shelter. It can coordinate economy, ritual and politics, simply by deciding who moves where and when. They also remind us that myth and architecture often travel together. Later stories about Minos and the Labyrinth are not random fantasies placed on a blank stage. They are one culture’s response to the impressive leftovers of another.

If this explainer has helped you picture yourself walking through Knossos or Phaistos, not just looking at plans from above, then it has done its job. From here, you might zoom in on a single staircase, a painted corridor, or a set of storerooms, and ask the same slow questions: what happens to a person’s experience when they pass this point. That is how these palaces start to feel less like puzzles on paper and more like lived spaces in a real Bronze Age world.

Sources and Further Reading

The Metropolitan Museum of Art — “Minoan Crete” (2002) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Smarthistory — “Minoan art, an introduction” (2020) (Smarthistory)

Khan Academy — “Minoan art, an introduction” (n.d.) (Khan Academy)

LibreTexts / Smarthistory — “Ancient Aegean” (section on Minoan palaces) (2021) (Humanities LibreTexts)

CWI Pressbooks — “Chapter 4: The Ancient Aegean” (Minoan palaces) (2024) (CWI Pressbooks)

Encyclopaedia Britannica — “Knossos” (revised ed.) (Encyclopedia Britannica)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin — “Art of the Aegean Bronze Age” (2012) (resources.metmuseum.org)