Daily Life in the Cyclades: Homes, Graves and Sea Routes

A detailed Minoan house model revealing multi-storey architecture and open-air spaces.

Picture a small Cycladic island at dawn. Low stone houses step down a slope. A goat bleats somewhere above the village. Down by the shore, a narrow boat is already sliding into the water, loaded with jars and a few passengers. Up on the ridge behind, a line of rock-cut graves looks out toward the sea.

This is Cycladic civilization in its everyday version. Not just the marble figurines we love, but the houses people slept in, the tombs they prepared, the sea routes they sailed again and again. It is an Early Bronze Age island world that feels tiny on the map and strangely big once you look at the evidence.

In this explainer, we will rebuild daily life as honestly as we can: where people lived and worked, how they buried their dead, and how the sea shaped everything from trade to risk. If you want a first overview of the objects themselves, you can pair this with our guide to Cycladic art and our close reading of Cycladic art figures. Here, our focus is on the people behind them.

Cycladic civilization is an Early Bronze Age island society

When we talk about Early Cycladic civilization, we mean the communities that lived on the Cycladic islands in the central Aegean Sea roughly between 3200 and 2000 BCE. These islands form a ring around Delos. They range from small rocky outcrops to larger places like Naxos and Paros. The geography matters immediately: short sea crossings, steep hills, limited farmland, and easy access to stone and harbours.

Archaeology suggests that people were already visiting some Cycladic islands for obsidian in the Neolithic, but it is in the third millennium BCE that we see a distinctive Cycladic culture take shape. Settlements appear on slopes near the coast or on naturally defensible headlands. Houses cluster in small groups rather than in huge cities. Pottery styles, marble vessels and figurines show a shared visual language across islands, even as each community keeps local quirks.

We often imagine Bronze Age Greece through big names like Knossos or Mycenae. Cycladic settlements are smaller, but they are not primitive. Excavations show stone foundations, planned clusters of rooms, storage areas and sometimes paved lanes. On Santorini (Thera), the later town at Akrotiri, with its multi-storey houses and drainage system, grows out of earlier Cycladic architecture traditions on the island.

The important thing is to hold two scales at once. On the ground, Cycladic civilization is made of small communities managing terraces, animals and local quarries. On the map, those same communities are nodes in a wider Aegean network that we usually group under Aegean art and Bronze Age culture. From their point of view, the sea is not a distant horizon. It is the road that connects home to everything else.

Definition: Cycladic civilization is the Early Bronze Age island society that flourished in the Cyclades from about 3200 to 2000 BCE, known for stone houses, rock-cut graves and distinctive marble figurines.

This restored house model highlights Minoan architectural complexity long before classical Greek architecture.

Homes and graves show how Cycladic communities organised life

If we want to feel daily life, houses and graves are our best entry points. They are the two spaces where people invested in structure: one for the living, one for the dead.

Cycladic houses are usually built from local stone, with mud mortar and flat roofs. Rooms tend to be small and rectangular, often grouped around a shared courtyard or lane. Many houses combine domestic space and work space, so cooking, weaving, storage and small-scale craft can happen in the same cluster. Finds of grinding stones, loom weights and pottery kilns suggest a busy, multitasking environment rather than a strict separation between home and workshop.

Food would have come from a mix of sources: barley and wheat on terraced fields, olives and vines where possible, sheep and goats on the hills, and fish or shellfish from the surrounding sea. Clay ovens and hearths inside houses leave traces of meals cooked and shared. Tools in metal and stone show how people repaired boats, made nets and handled daily tasks. This is not an isolated peasant world. It is a flexible economy that leans on both land and water.

Graves, often cut into rock or built with stone slabs, give us a different angle on Cycladic values. People were buried uncremated, usually in a contracted or slightly curled position. They were often accompanied by objects used in daily life, like vases, tools and jewellery, along with pieces that might have been made specially for burial. This is where the marble figurines we now call Cycladic art figures appear in large numbers: lying beside the dead, sometimes more than one per grave.

The pattern is consistent enough to draw a simple conclusion. Cycladic communities did not see a sharp break between life and death. They chose to send certain everyday objects and symbolic pieces into the ground with their dead. Graves look like compressed versions of life: a body, a few possessions, and one or more carefully made images. If houses show how Cycladic people organised space for the living, graves show how they compressed identity and memory for the long term.

Mini-FAQ

Did every Cycladic person get a marble figurine in their grave?

No. Figurines appear regularly, but not in every burial, which suggests differences in access, status or family tradition.

Were Cycladic graves separate from settlements?

Often they are on slopes or low ridges near villages, sometimes in clusters, so the living and the dead share the same broader landscape rather than being completely separated.

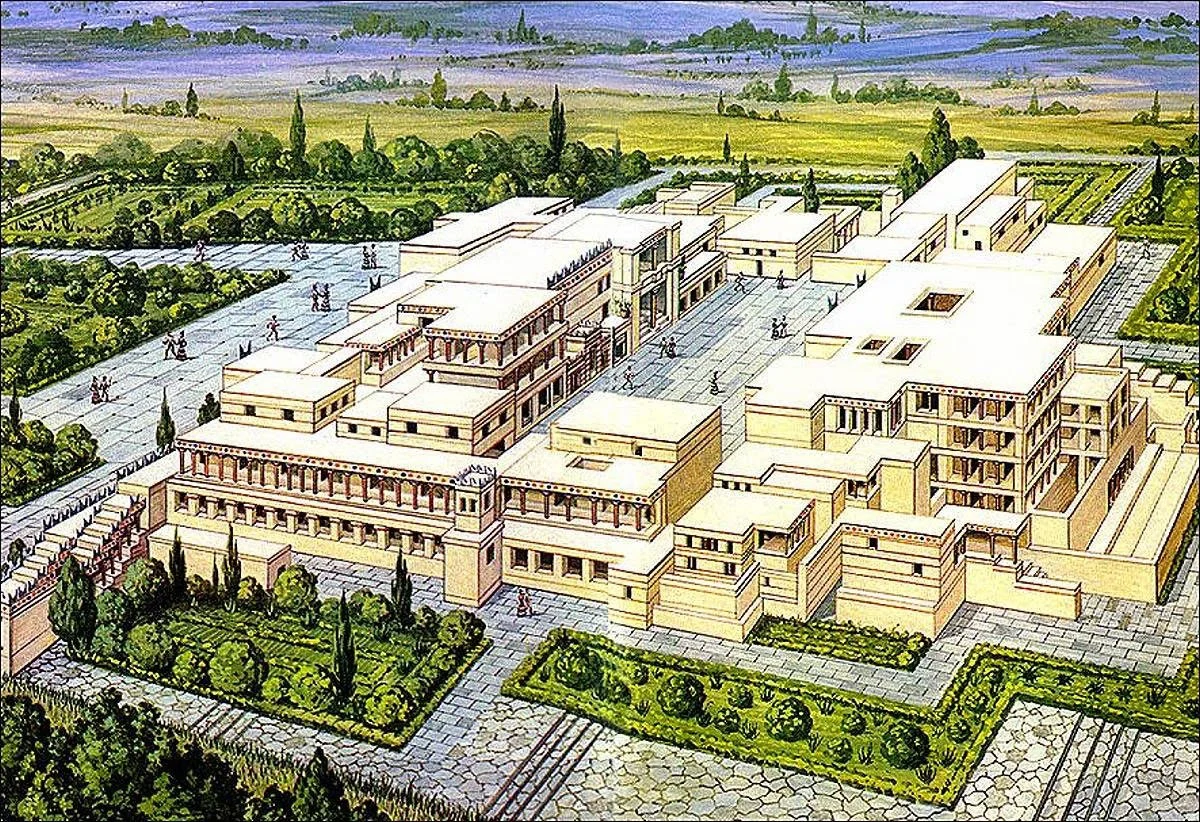

A modern reconstruction of the Palace of Knossos, imagining its vibrant gardens and sprawling courtyards.

Sea routes connect Cycladic islands to a wider Aegean world

If Cycladic houses and graves tell us about the inside of the society, sea routes tell us about the outside. The Cyclades sit right in the middle of the Aegean, so almost any journey between mainland Greece, Crete and Asia Minor passes near them. That position is not an accident of our map view. It is a major reason Cycladic civilization develops the way it does.

Archaeologists find foreign pottery and materials at Cycladic sites, including pieces from the Greek mainland, Crete and western Anatolia. Cycladic marble figurines and vessels travel in the opposite direction. They appear in Cretan and mainland contexts, sometimes as imports, sometimes as local imitations. Obsidian from Melos, a volcanic glass ideal for blades, turns up widely, proving that people are moving goods by sea in a regular way.

Some islands become especially important in this maritime network. Keros and the nearby islet of Dhaskalio, for instance, seem to form an early maritime sanctuary and settlement centre. Archaeological work there shows terraced constructions, imported materials and evidence of ritual activity involving broken figurines and pottery. The so-called Keros-Syros culture, one phase of Early Cycladic history, is even named after this area, which hints at its regional significance.

Further south, Akrotiri on Thera grows from a small settlement into a sophisticated port town, plugged into routes that connect Crete, Cyprus and the eastern Mediterranean. Its later destruction by the Theran eruption in the 16th century BCE froze a moment of Cycladic-Minoan contact under volcanic ash. Even before that, however, Akrotiri and similar ports show us that Cycladic islands are not remote edges. They are stopovers, meeting points and hubs.

For Early Cycladic communities, the sea is both barrier and bridge. It protects them from easy land invasion but exposes them to storms, shipwrecks and dependence on trade for certain metals and goods. One modern archaeologist described it neatly: the sea plays a double role as obstacle for land people and highway for seafarers. That double nature shaped everything from settlement choices to the kinds of stories people might have told about risk and luck.

The so-called Throne Room at Knossos, with its vivid red walls, benches, and basin, shows how architecture and painting framed elite ceremonial spaces in Minoan palaces.

Conclusion: Why Cycladic civilization still matters for us

It is easy to meet Cycladic civilization only in the museum, in the form of a single marble figure on a clean plinth. Once we zoom out to houses, graves and sea routes, the picture changes. Those figurines go back to being what they really were: one piece of a broader island society that handled stone, sea and memory with a lot of quiet skill.

For me, the main takeaway is that small places can have big histories. Cycladic communities never build vast palaces or empires, but they help shape the early Bronze Age Aegean anyway. Their boats move raw materials, their workshops test ideas about form, and their burial customs give us a rare look at how early islanders faced death. When later cultures in Greece and Crete rise, they inherit a seascape already mapped by Cycladic routes and experiences.

If you carry this view forward into the rest of Aegean and Greek art, it changes the feeling a little. The story of the region stops being a straight line from “primitive islands” to “advanced mainland” and becomes a network of experiments, where even small rock outcrops contribute to the shared visual and social toolkit. Cycladic civilization is not a footnote. It is an early chapter in how communities around this sea learned to live with limited land, abundant stone and a demanding but generous horizon.

Sources and Further Reading

Museum of Cycladic Art — “The Archaeology of the Cyclades in the Early Bronze Age” (n.d.) (Cycladic)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art — “Early Cycladic Art and Culture” (2004) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Smarthistory — “Cycladic art, an introduction” (2020) (Smarthistory)

Greece Is — “Unraveling the Mysteries of Early Cycladic Culture” (2024) (Greece Is)

Greek News Agenda — “Keros Project: Uncovering the Mysteries of Cycladic Civilization” (2024) (Greek News Agenda)

Latsis Foundation — Prehistoric Thera (n.d., PDF) (Κοινωφελές Ίδρυμα Ιωάννη Σ. Λάτση)

Smarthistory — “Cycladic” culture overview (n.d.) (Smarthistory)