Greek God Statues: How the Gods Looked in Ancient Greek Art

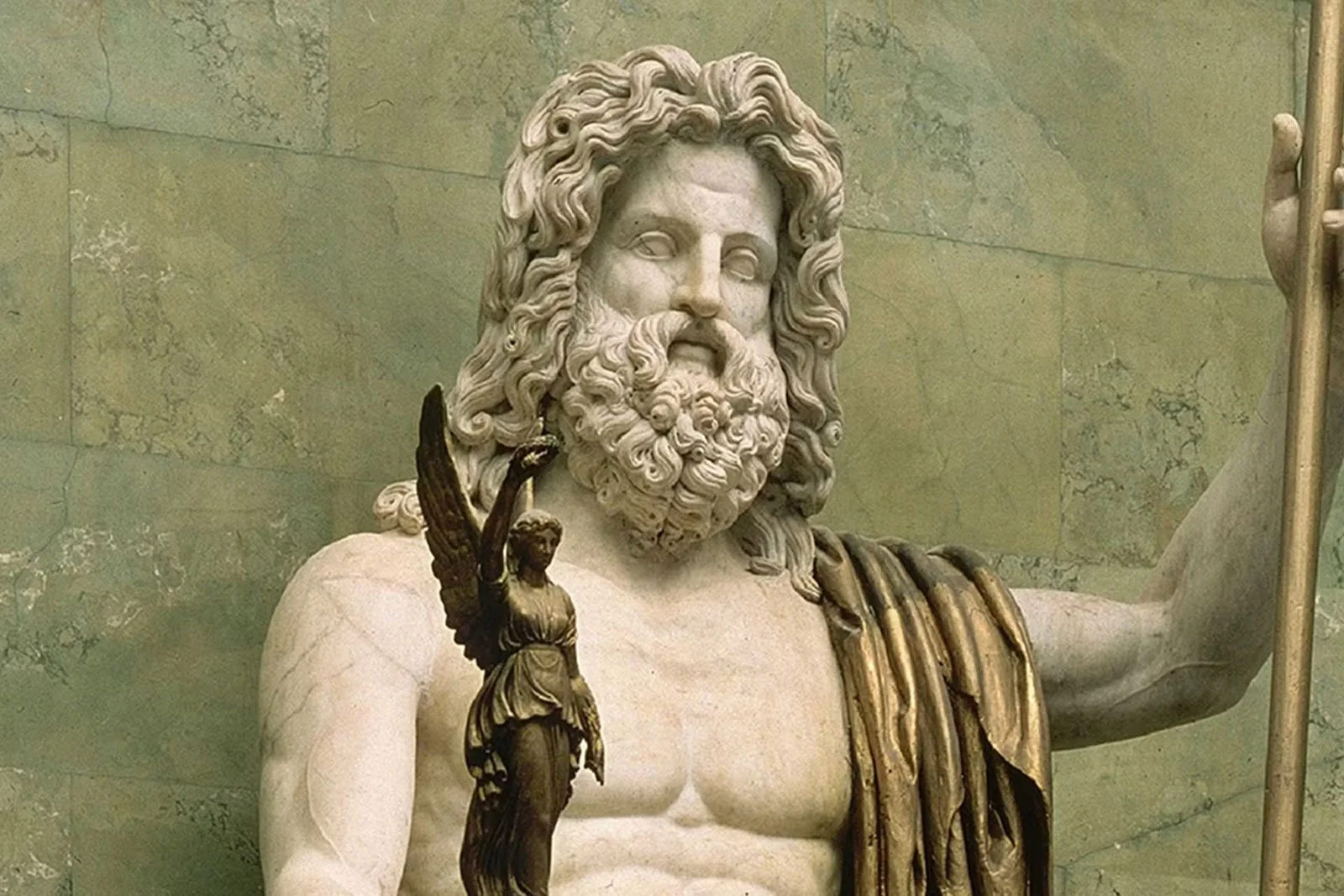

This Zeus shows how cult statues projected divine power into civic space, towering above worshippers as a perfected, unreachable image of authority.

Imagine walking into a museum room full of marble bodies. Some sit on thrones, some stand, some almost glide forward. One holds a thunderbolt, another a small winged figure, another just gathers a cloak around her. No labels, no school group, just you and a crowd of silent gods.

This is where Greek god statues become more than “old sculpture.” They are the main way the Greeks made Zeus, Athena or Aphrodite visible, solid and present. In this guide, we walk through how these divine images worked: what made them “god-like,” how cult statues filled temples, and how attributes – a helmet here, a dove there – turned anonymous marble into a specific deity. Along the way, we link back to what you already know from ancient Greek sculpture, ancient Greek art and ancient Greek religion.

Greek gods were imagined as perfect, human-shaped bodies

A simple but important point first: Greek gods looked like humans made perfect. They were not animals, monsters or formless clouds. They were taller, stronger and impossibly beautiful versions of men and women, with bodies that seemed to never age.

In statues, you see this in two big choices: nudity and drapery. Male gods like Zeus, Poseidon or Apollo often appear nude or nearly nude, showing controlled muscles rather than brute bulk. The body is calm, symmetrical, balanced – a visual shorthand for divine power in harmony. Female goddesses like Athena or Hera are usually wrapped in layered garments, but the folds still hint at a strong body underneath. If you have looked closely at works like the Peplos Kore, you know how much Greek sculptors loved using cloth to suggest shape, movement and status.

This human-like appearance matters for religion too. In ancient Greek religion, gods interact with humans all the time – in myths, oracles, dreams, festivals. Making them look like ideal people made those interactions feel possible. When you stood in front of a statue, you were not looking at a symbol in our modern sense. You were looking at the kind of body a god might choose if they walked into your sanctuary.

Definition

A Greek god statue is a sculpted image – often marble, bronze or gold-and-ivory – that represents a specific deity for worship, display or dedication in a sanctuary.

Apollo’s marble body twists in a graceful contrapposto, cloak slipping from his shoulder, a model of ideal classical masculinity.

Cult statues made gods feel present inside temples

Not all statues of gods were equal. At the top of the hierarchy stood cult statues – the main image of a deity housed inside a temple’s inner room. These statues were the focus of rituals, dedications and processions. In some cases they were relatively modest stone figures. In others, they were spectacular constructions of gold and ivory built by famous sculptors.

Two lost works often used as textbook examples are Phidias’ cult statues of Zeus at Olympia and Athena in the Parthenon. Both were chryselephantine sculptures, built around a wooden core, with ivory for the flesh and gold for drapery and armour. The Zeus at Olympia sat on a richly decorated throne, holding a small Nike (Victory) in one hand and a sceptre topped with an eagle in the other. The Athena Parthenos stood fully armed, with spear, shield and helmet, towering almost up to the temple roof. Contemporary descriptions stress not only size and luxury, but also the feeling that the god truly filled the space.

Here, our earlier guides to ancient Greek sculpture and Greek temple design slot into place. The long cella of a temple framed the approach to the cult statue. Columns, steps and doorways controlled how much you could see at once. Oil, water basins and polished surfaces helped bounce light onto gold and ivory. The result was carefully staged: when you entered, the god did not just “appear.” The architecture and the statue together produced an encounter.

Even outside these showpiece works, many sanctuaries held large standing or seated god statues. Smaller bronzes, terracotta figurines and reliefs filled the surrounding spaces as dedications from worshippers. The big cult image anchored the site, but the whole sanctuary functioned as a landscape of divine presence.

Bronze figure of a Greek god, identified as Zeus or Poseidon, showing the idealized athletic body of an Olympian god.

Each god had a visual “signature” of poses and symbols

Once you start looking, you notice that every major deity has a visual signature – a mix of pose, clothing and attributes that keeps repeating. Artists and viewers shared this mental checklist, so even a fragment of a statue could be enough to signal a particular god.

A few quick examples you will bump into again and again:

Zeus: often bearded, powerful and mature, either seated on a throne or standing with a raised arm. He may hold a thunderbolt, a sceptre or a small Nike. The overall mood is controlled authority, not wild violence.

Athena: helmeted, armed and usually clothed in a long peplos or chiton. She carries a shield, spear and sometimes a small winged Nike on her hand. Snakes, owls and the gorgon head appear as recurring motifs. Our dedicated piece on Athena’s symbols dives deeper into these details.

Aphrodite: often shown in a softer, more sensual way. In later periods, she can be partially or fully nude, adjusting her garment or stepping out of a bath. Doves, mirrors and shells may appear as props.

Apollo: youthful, often nude or lightly draped, sometimes with a lyre or bow. His statues balance athletic ideal with a slightly distant, refined calm.

Dionysos: can be bearded or youthful, but tends to appear with a drinking cup, ivy wreath, panther or satyr. His body language is looser, less rigid than other gods, especially in Hellenistic works.

When you read myths or works like those discussed in ancient Greek art, these visual codes keep popping up. A viewer in antiquity did not have to guess who a statue showed. They could “read” attributes just like we read traffic signs.

The same is true on a smaller scale in statues that blur the divine and the human. The Anavysos Kouros is a grave marker, not a specific god, but his idealised body and serene face echo how gods were imagined. The Peplos Kore might represent a mortal girl, a generic worshipper or a goddess herself. That ambiguity is part of the point: the closer a human statue moves toward the “god look,” the more it hints at status, virtue and divine favour.

Marble Diana strides forward, hand reaching for an arrow, a Roman copy that shows how Greek goddesses were imagined in action.

From archaic smiles to classical calm in divine faces

If you line up Greek god statues across time, another pattern appears: the style of divinity shifts. In the Archaic period, statues of gods and humans share the same frontal stance, patterned hair and characteristic archaic smile. The faces are not smiling because the gods are happy. The tight, upturned lips probably helped carve the mouth and suggested a kind of life force.

By the early Classical period, that expression fades. Faces become quieter; eyes and lips relax. Bodies twist slightly, weight rests on one leg, shoulders tilt. This famous contrapposto stance shows up in mortal athletes and in divine figures alike. For gods, this new style suggests a different kind of power. Instead of rigid frontality, you get calm control: a sense that the god could move, speak or act at any moment, but is choosing stillness.

Later, in Hellenistic works, gods can become more emotional or theatrical. Think of dramatic Zeus-like figures hurling thunderbolts, or sensual Aphrodites stepping out of the sea. Sculptors experiment with age, movement and mood. Yet even here, earlier choices still echo in the background. A bearded, muscular thunderbolt-wielder remains Zeus; a draped, armed woman with helmet remains Athena. The iconography holds, even as the style shifts.

If you keep ancient Greek sculpture in mind as a whole, god statues become a kind of spine running through it. They absorb stylistic change, stabilise religious expectations and offer artists the ultimate challenge: how to make an invisible, powerful being feel convincingly present in stone or bronze.

Conclusion

Greek god statues sit at the crossroads of story, ritual and design. On the surface, they are beautiful bodies in marble and bronze. Underneath, they are the main way Greeks pictured their gods at human scale. Cult statues turned temples into meeting points with divinity. Attributes and poses gave each deity a visual signature. Shifts from archaic smiles to classical calm, and then to Hellenistic drama, show changing ideas about what divine presence should feel like.

For us, learning to read these figures is a slow but rewarding skill. Every time you recognise Zeus’ raised arm, Athena’s shield or Aphrodite’s half-adjusted drapery, you are stepping a little closer to how ancient viewers moved through sanctuaries and city streets. From here, you can loop back into ancient Greek religion for the rituals, or into ancient Greek sculpture for the techniques and workshops behind these works. The gods may no longer be worshipped, but their statues still quietly train our eyes.

Sources and Further Reading

Metropolitan Museum of Art — “Greek Gods and Religious Practices” (2003)

Metropolitan Museum of Art — “Greek Art in the Archaic Period” (2003)

World History Encyclopedia — “Statue of Zeus at Olympia” (2018)

World History Encyclopedia — “Athena Parthenos by Phidias” (2015)

Wikipedia — “Chryselephantine sculpture” (overview of gold-and-ivory cult statues)

Metropolitan Museum of Art — “Art of the Hellenistic Age and the Hellenistic Tradition” (2007)

Museo del Prado — “Athena Parthenos” (Roman copy of the cult statue)