The Labyrinth and the Minotaur: From Knossos to Later Greek Art

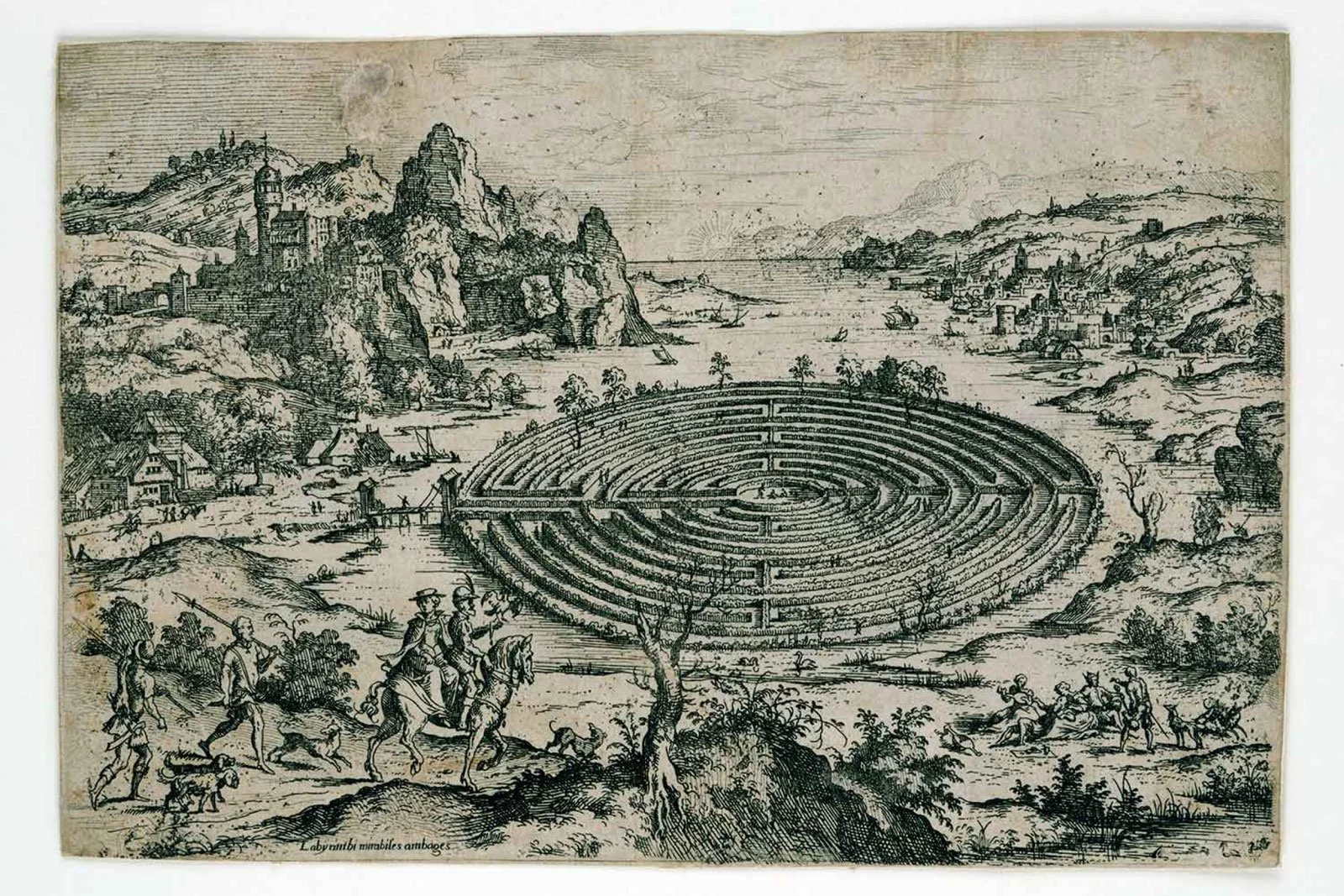

This 16th-century engraving shows how the mythic Cretan Labyrinth was reimagined as a formal garden, turning an ancient story into a device for landscape design.

A dark stone corridor, a smell of damp earth, heavy breathing in the dark. Somewhere ahead, hooves scrape against the floor. You are holding a sword in one hand and a thread in the other. If you lose either, you do not get out.

This is the atmosphere behind the myth of the Minotaur and the labyrinth. It starts in stories about Crete and King Minos, but very quickly spills into vase painting, temple sculpture and, much later, modern illustration and film. The monster and his maze are almost like a reusable template: every era redraws them to express its own fears about power, violence and getting lost.

In this piece, we will do three things together. First, retell the core myth of Theseus, Ariadne and the labyrinth. Second, place that story next to the real Minoan palaces at Knossos and Phaistos, which likely helped inspire it. Third, follow the Minotaur across Greek vases, Roman mosaics and later art to see how the image keeps changing. If you want the architectural side in more detail, you can pair this with our guide to Minoan palaces and the broader overview of Minoan civilization.

The core story: Theseus, Ariadne and the Cretan maze

At the heart of the Greek labyrinth myth is a triangle: Minos, Theseus and the Minotaur. The details shift a bit from source to source, but the main arc is stable enough to follow.

King Minos rules Crete. In one version, he asks Poseidon for a sign of divine support and receives a magnificent white bull from the sea. Instead of sacrificing it back, he keeps the bull, and the god punishes him. Minos’ wife, Pasiphae, is made to fall in love with the animal and later gives birth to a hybrid child: the Minotaur, a creature with a bull’s head and human body. Ashamed but unable to kill it, Minos orders the craftsman Daedalus to build a structure so complex that the monster can never escape. This is the labyrinth, usually placed at Knossos.

At the same time, Athens is forced to send regular tributes of youths and maidens to Crete, who are thrown into the labyrinth as food for the Minotaur. Theseus, a prince of Athens, volunteers to go with one of these groups. When he arrives in Crete, Minos’ daughter Ariadne falls in love with him and decides to help. She gives him a ball of wool, the famous Ariadne’s thread. Theseus ties the end at the entrance, goes in, kills the Minotaur and then follows the thread back out, bringing the other youths with him.

The story already compresses several ideas into one narrative. There is a political element (Athens freed from Cretan control), a coming-of-age story (Theseus proving himself), and a first sketch of the labyrinth as something that is not only physical but also mental: a place where you lose orientation and need a strategy to escape. Later retellings add moral tones, love triangles and tragic endings, but the essential image remains the same. A confusing structure, a monster at the centre, a hero navigating both.

Definition: In Greek mythology, the Labyrinth is a complex structure built by Daedalus for King Minos of Crete, designed to hold the Minotaur until Theseus kills it and escapes with Ariadne’s help.

This detailed view of a circular labyrinth shows how early modern artists imagined the Cretan maze as a walkable garden woven into a real landscape.

Knossos and the “real” labyrinth: palaces that feel like mazes

So where does this story touch actual Bronze Age Crete. Here we step from myth into archaeology. At Knossos, Phaistos and other sites, excavations have uncovered sprawling Minoan palaces with hundreds of rooms, storage magazines, staircases and corridors. Walking through Knossos, even as a modern visitor with a plan, you can understand why later Greeks might imagine a maze.

We know that Knossos was a major centre of Minoan civilization from around 1900 BCE onward. Its central court is surrounded by multi-level wings filled with storerooms, small shrines, halls and workspaces. Light wells punch daylight deep into the interior. Stairs connect floors in indirect ways. From inside the building, your view keeps changing: now a glimpse of the court, now a narrow corridor, now a recessed chamber. There is no single straight axis that shows you the whole structure at once.

Later Greek visitors would not have seen the palace exactly as we reconstruct it now, but they would have encountered ruins with enough complexity to feel uncanny. Stone foundations, bits of painted plaster, pieces of bull-horn symbols and large jars all hint at a powerful earlier culture. Add oral memories and local stories about a great king and his sea power, and the idea of a labyrinth at Minos’ court feels like a natural narrative reaction, not a random invention.

Bull imagery strengthens the link. Minoan art is full of bulls: bull-head drinking vessels, horn motifs on palace roofs, and dynamic scenes of bull-leaping, where acrobats vault over animals in front of an audience. In our dedicated guide to Minoan bull-leaping, we look closely at how these images work. For a later Greek mind, this intense bull symbolism, plus confusing architecture, plus stories of Cretan power over the sea, could easily crystallise into the figure of a bull-man trapped in a maze.

Myth vs Fact

Myth: There was a literal underground stone maze beneath Knossos where the Minotaur lived.

Fact: Archaeology shows no such underground maze; the “labyrinth” idea probably grew from the complex multi-level plans of Minoan palaces and later Greek attempts to explain them.

Theseus and the Minotaur on Greek vases: from horror scene to civic icon

Once we move into historical Greece, the Theseus and the labyrinth story appears everywhere. Vase painters love it, because it gives them a clear, dynamic pairing: hero and monster, in close combat, framed by architecture.

On Archaic black-figure vases, the Minotaur is often shown kneeling or half-collapsing, with a human body and bull’s head, while Theseus drives a sword into his chest or neck. One black-figure neck amphora in the British Museum shows Theseus seizing the Minotaur by the horn with one hand and stabbing with the other, blood streaming from the wound. The monster sometimes holds a stone, as if about to fight back, but the outcome is never in doubt.

By the Classical period, red-figure painters refine the scene. On an Attic kylix attributed to the Codrus Painter, Theseus drags the Minotaur’s body out of a building, hinting at the exit from the labyrinth. The composition is tight and theatrical. The building stands in for the maze; the doorway is the threshold between danger and safety. The labyrinth itself is not a complex plan here, just a solid architectural block that signals “inside” versus “outside”.

What is striking is how often Theseus looks almost relaxed. He is the ideal ephebos, the young citizen-in-training, well proportioned and lightly armed. Athens, which promotes Theseus as a founding hero, uses these images to say something about itself. The city is brave enough to face foreign monsters, clever enough to escape complex traps, and generous enough to free others from tribute. In that sense, the Minotaur labyrinth motif becomes a political logo. It frames Athens as the opposite of the dark, oppressive maze.

The story also moves into coinage and public art. Knossos itself later mints coins with labyrinth patterns and Minotaur heads, while Athenian and other Greek workshops repeat the theme in relief and small sculpture. Already in antiquity, then, the myth is doing double duty: it entertains and it brands.

The tondo of this drinking cup turns the Minotaur into a bold graphic silhouette, reminding us how Greek myth travelled on everyday objects as well as in epic poetry.

Labyrinths after Greece: mosaics, cathedrals and modern psychology

The labyrinth does not stay in Crete. Once the myth is in circulation, its central image, a winding path with a centre, keeps reappearing in new contexts. The labyrinth Greek mythology story becomes a template for thinking about complexity, sin and the self.

In Roman times, mosaic floors sometimes show maze patterns with Theseus and the Minotaur at the centre. The labyrinth is both a visual puzzle and a narrative stage: you literally walk on top of the story as you cross the room. In Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the Minotaur often disappears, but the maze remains. Cathedrals such as Chartres and Lucca include stone or inlaid labyrinths on floors or walls. In Lucca, an inscription explicitly refers back to the Cretan labyrinth and Theseus, turning the pattern into an allegory of the soul’s journey through sin.

Later art and literature pull the myth in yet more directions. Nineteenth and twentieth century artists depict the Minotaur as a tragic outsider, a victim of other people’s choices. Modern writers and filmmakers turn the labyrinth into a metaphor for the unconscious, for bureaucracy, for modern cities. The monster is sometimes less frightening than the structure itself. The key switch is that the labyrinth stops being only a building and becomes a mental or social condition.

At the same time, very contemporary visual culture keeps returning to the classical version. Graphic novels, fantasy films, video games and even tourist logos reuse the bull-headed creature and the twisting corridors of an underground maze. The story survives because it is flexible. You can make the monster stand for anything: foreign threat, internal rage, trauma, oppressive systems, or just a good old-fashioned boss fight at the end of a level.

Conclusion

The Minotaur and his labyrinth are a good reminder that myths are not fixed texts. They are processes. They start close to real places and practices, like Minoan palace architecture and bull rituals on Crete, and then they keep drifting, picking up new meanings as they pass through Athens, Rome, medieval cathedrals and modern studios.

For us, as learners, the interesting part is how story, building and image keep talking to each other. Once you have walked, even in your imagination, through the ruins of Knossos in our article on Minoan palaces, the labyrinth myth stops feeling like pure fantasy. Once you have looked closely at Greek vases and later artworks, the monster stops being only a scare figure and starts to look like a mirror for whatever the artist’s world is worried about.

If this guide leaves you with a clearer picture of how the Minotaur labyrinth myth grows out of Crete and then spreads across art history, you already have a strong base for exploring related stories. From here, you might zoom in on Theseus himself in our dedicated piece on Theseus and the labyrinth, or on the real bull-leaping performances behind the images in Minoan bull-leaping. The thread is in your hand now; you decide where to go next.

Sources and Further Reading

Labyrinth — “In Greek mythology, the Labyrinth is an elaborate, confusing structure built for King Minos of Crete” (n.d.) (Wikipedia)

Knossos — “Bronze Age archaeological site and centre of Minoan civilization” (n.d.) (Wikipedia)

British Museum — “Black-figured neck-amphora: Theseus slaying the Minotaur” (G 1843,1103.21) (British Museum)

British Museum — “Attic red-figured kylix: Theseus and the Minotaur” (G 1850,0302.3) (British Museum)

National Archaeological Museum of Athens — “The face of the beast: Asterion, the Minotaur” (n.d.) (Eθνικό Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο)

Finestre sull’Arte — “The labyrinth of Lucca Cathedral: a sacred symbol linked to Greek myth” (2024) (Finestre sull'Arte)

Hellenic Museum — “Theseus and the Minotaur: the man, the myth and the science” (2020) (hellenic.org.au)