Types of Columns: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian for Beginners

Corinthian columns show Greek architecture at its most ornate, fluted shafts crowned by acanthus leaves that almost seem to burst into real foliage.

If you have ever stared at a temple photo thinking “nice columns, but which type is which?”, you are not alone. The big three orders — Doric, Ionic and Corinthian — are often thrown at us as if they were self-explanatory. In reality, they only become memorable when we slow down, put them side by side, and learn a few quick visual cues we can actually test in the wild.

In this guide, we treat column types like three characters in the same story. We will start from the ground up, look at bases, shafts and capitals in turn, and keep tying everything back to real buildings from our articles onGreek architecture,Greek temples and otherancient Greek structures. The goal is simple: by the end, you should be able to glance at a column and say “Doric”, “Ionic” or “Corinthian” with calm confidence.

Column types are a visual shortcut to reading Greek buildings

Learning the basic types of columns is not about passing an exam. It is about having a fast way to understand what kind of building you are looking at, when it was designed, and what mood it is aiming for. Ancient architects used Doric, Ionic and Corinthian like different voices: sturdy, elegant or lush.

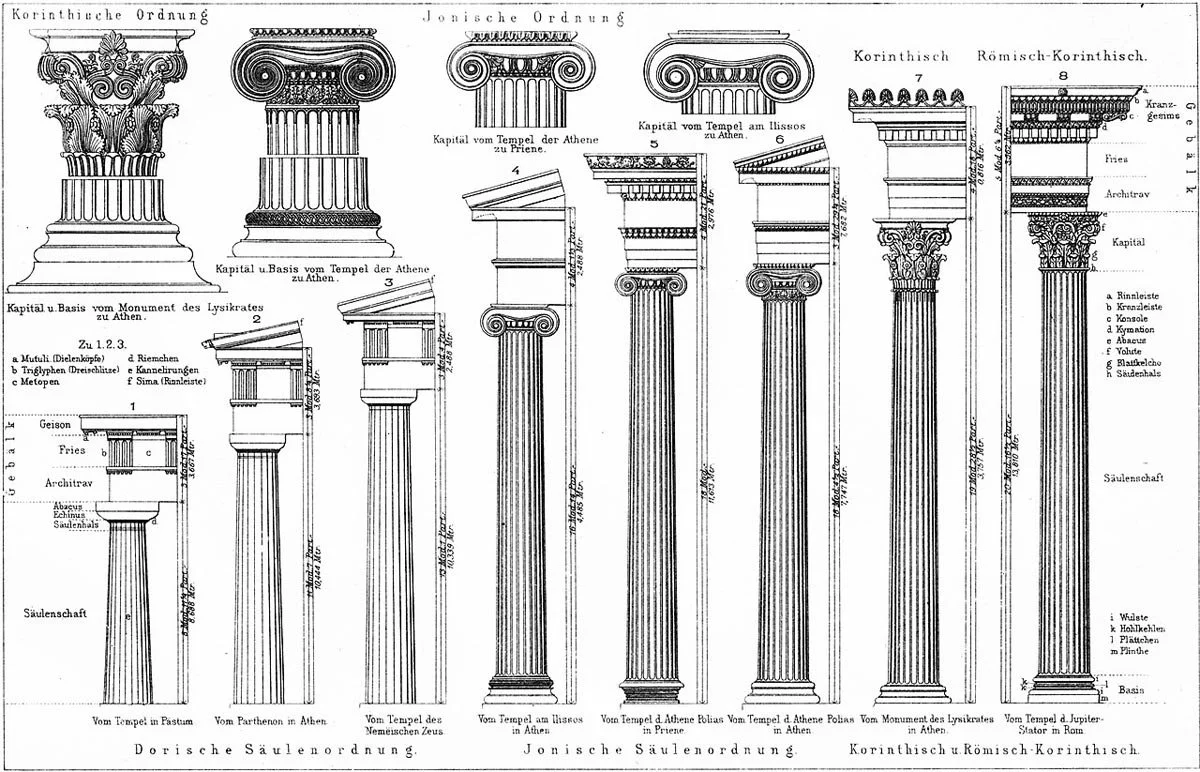

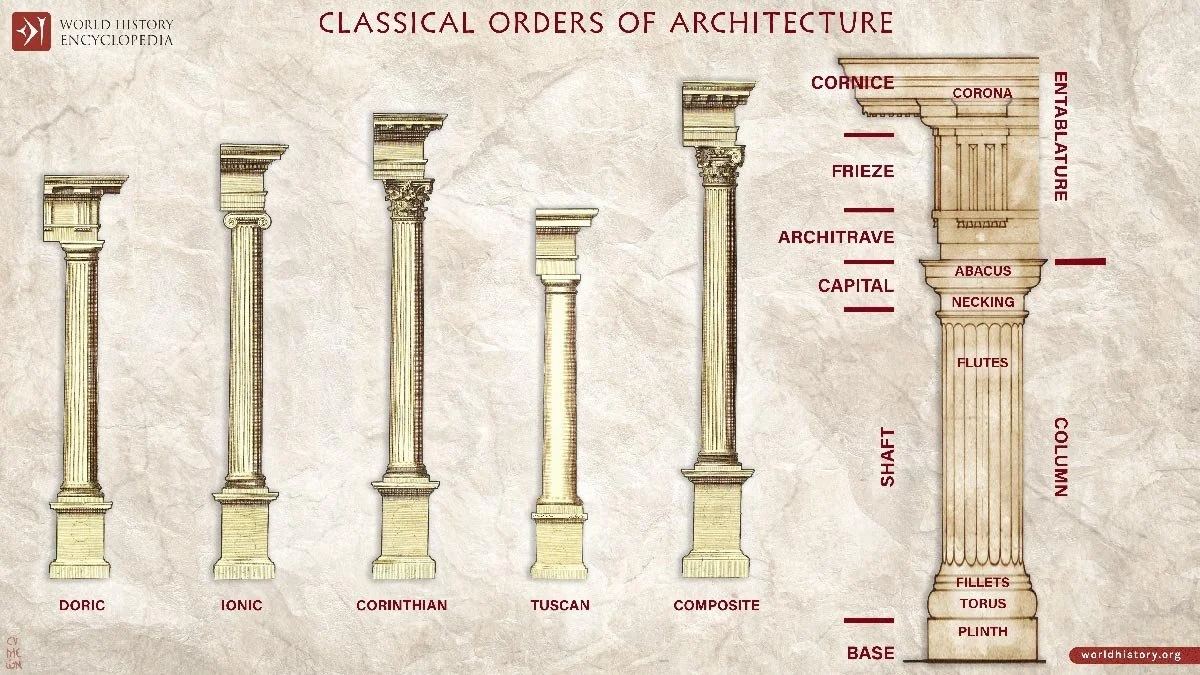

Each “order” is a full system, not just a capital style. It includes the column (base, shaft, capital) and the entablature (the horizontal beam on top). Doric, for example, usually comes without a base and has a frieze of alternating triglyphs and metopes above; Ionic sits on a moulded base, has a continuous sculpted frieze, and caps itself with scrolls. Corinthian keeps the Ionic base and general proportions, but switches in a leafy capital that looks almost like a carved bouquet.

In our broader overview of Greek architecture, these orders are the grammar behind façades. A Doric ring of columns around a temple tells you one kind of story; an Ionic colonnade wrapping an inner room tells another. Later, Romans will happily mix and multiply orders, but the core vocabulary is Greek. Once you can read it, even ruins feel less intimidating and more like a language you are slowly learning.

Mini-FAQ

Q: What are the three main Greek column types?

A: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian are the three classical Greek orders of columns.

Q: Which column is the most decorative?

A: The Corinthian order, with its leafy capital, is the most ornate of the three.

Engraving that lines up Doric, Ionic and Corinthian columns as a visual glossary of how bases, shafts and capitals differ between orders.

Doric: thick, no base, simple capital, strong rhythm

Doric is the sturdy, no-nonsense order. If you want a mental image, think of the Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis: wide columns, no separate bases, simple round-plus-square capitals, and a very clear rhythm of vertical shafts and horizontal beams.

Structurally, a Doric column usually stands directly on the stylobate (the upper step of the platform) with no moulded base in between. The shaft is relatively short and thick, often with twenty shallow flutes that meet in sharp edges. The capital is made of two parts: a cushion-like echinus (a simple, rounded element) and a flat square abacus on top. Above, the entablature carries a frieze with triglyphs (blocks with three vertical grooves) and metopes (square panels that can be plain or sculpted). That triglyph-metope pattern is one of your fastest Doric clues.

Mood wise, Doric feels solid, weighty and slightly conservative. It appears early, especially in mainland Greece and Magna Graecia, and suits temples that want to project strength and clarity. Our dedicated piece on the Doric column will go deeper into proportions and regional quirks, but for now you can think: no base, chunky shaft, simple capital, triglyph frieze. If those four boxes are all ticked, you are almost certainly in Doric territory.

Doric also has a strong connection to geometry and structure, which links nicely back to earlier building types like the megaron. It is as if Greek architects took the basic rectangular hall and wrapped it in a rigorous colonnade that makes the load-bearing system visible. Once you see that, Doric stops being a style label and becomes a way of thinking about weight, support and rhythm.

Doric column and capital at Paestum. Its squat, cushion form mirrors the simple stone supports of early Greek houses.

Ionic: slim, with a base and elegant scrolls

If Doric is the strong voice, Ionic is the more lyrical one. Its columns are slimmer, stand on moulded bases, and carry capitals that curl into characteristic volutes, the scroll shapes you have probably seen a hundred times without naming them.

Start again from the ground. An Ionic column normally rests on a base of stacked mouldings rather than directly on the stylobate. The shaft is taller and more slender than Doric, often with more and deeper flutes that create a finer play of light and shadow. At the top, the capital has two large volutes, like spirals or rolled-up scrolls, often sitting above a band of carved leaves or egg-and-dart pattern. Above, the entablature typically carries a continuous frieze, a long sculpted band rather than the broken rhythm of triglyphs and metopes.

Geographically, Ionic has strong ties to the eastern Greek world, especially Ionia on the coast of modern Turkey, before it spreads widely. In our explainer on Ionic columns, you will see how this order often appears in more delicate contexts: smaller temples, inner rooms, stoas, and combinations with Doric on the same building. The Parthenon itself is a famous hybrid, with a mostly Doric exterior but an Ionic frieze wrapped around its inner cella.

Visually, it helps to remember Ionic as base + scrolls. If you spot a clear base under the shaft and scroll capitals at the top, you are almost certainly dealing with Ionic, especially if the frieze above is one long, carved strip. That combination gives many buildings a lighter, more elegant profile, which Greek and later Roman architects used when they wanted something less heavy than Doric but not as flamboyant as Corinthian.

Section of a gigantic Ionic column from the Temple of Artemis at Sardis, displayed at the Met to evoke the scale of Hellenistic temples. Credits: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Corinthian: leafy, late and often used for show

Corinthian is the show-off of the three. It arrives later, is used more sparingly in Greek architecture, and becomes a favourite in the Roman world precisely because of its lush, detailed capital. If Doric is about strength and Ionic about elegance, Corinthian is about ornamental richness.

Technically, a Corinthian column shares much with Ionic: it usually stands on a similar base and has a comparable slender shaft. The real difference sits in the capital. Instead of scrolls as the main feature, Corinthian capitals are built from layers of carved acanthus leaves, often rising in two or three tiers, with small volutes or tendrils curling out near the top. The whole thing looks almost like a stylised plant sprouting from the top of the column.

Ancient writers linked the order to the city of Corinth and to a legendary sculptor who supposedly took inspiration from leaves growing around a basket. Whether or not that story is true, the key point is that Corinthian feels more luxurious and decorative. In the Greek world, it appears first in certain interiors and smaller monuments, then becomes more common in Hellenistic contexts. The Romans later adopt and multiply it, combining it with their own patterns so enthusiastically that we sometimes forget its Greek roots.

For a beginner, the rule of thumb is simple: if the capital looks like a carved bouquet with layered leaves and small scrolls, it is Corinthian. Our articles on Greek temple design and ancient Greek structures will show where it appears in relation to Doric and Ionic, and how its visual complexity plays against simpler wall surfaces and mouldings.

Corinthian capital from a grand sanctuary. Its leafy design later influenced columned courts in upscale Greek houses.

How to actually recognise Doric, Ionic and Corinthian in the wild

Knowing the textbook definitions is one thing; being able to spot orders on a ruin, a museum model or even a neoclassical building in your city is another. Here are a few small habits that make the types of columns stick.

First, start from the bottom. Ask: is there a clear, moulded base under the shaft, or does the column seem to sit directly on the platform? No base usually means Doric. A noticeable base, especially with stacked rings, points to Ionic or Corinthian.

Second, scan the capital. Is it a simple rounded cushion plus square slab? That is Doric. Are there two big scrolls curling out to the sides? That is Ionic. Is the whole capital a thicket of carved leaves, sometimes with tiny scrolls peeking out at the top? That is Corinthian. This three-step check takes seconds once you get used to it.

Third, look at the frieze and patterns above. Triglyphs and metopes mean Doric; a continuous sculpted band hints at Ionic or Corinthian. As you train your eye, you will also start noticing smaller decorative motifs that echo the orders, like the key patterns and other borders we explore in our guide to Greek patterns.

Finally, remember that not every building is a pure textbook case. Hybrids exist, especially in complex sanctuaries and in later periods. That is part of the fun. The orders are a toolkit, not a rigid law. When you already know the basic Doric–Ionic–Corinthian trio, you are better equipped to notice when a building bends the rules on purpose and to ask why.

Teaching graphic summarising Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, Tuscan and Composite orders, naming the main elements of column and entablature. Credits: World History Encyclopedia

Conclusion

Learning the types of columns is a bit like learning to read musical notation. At first, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian feel like abstract names. After a while, they become practical shortcuts that let you read buildings quickly and ask better questions. We have seen how Doric gives weight and clarity, how Ionic adds bases and scrolls for a more graceful profile, and how Corinthian crowns columns with carved leaves when a design needs overt richness.

For me, the best part is realising that column types are not just about style; they are about choices made on specific sites, in specific cities, by architects and patrons who wanted their temples and stoas to speak a certain way. If you pair this article with our broader map of Greek architecture and earlier explorations of building forms from the megaron to full Greek temples, you will start seeing the orders as part of a longer story about how people in the ancient world organised space, structure and meaning.

Next time you pass a row of columns, ancient or modern, try a quick scan: base or no base, simple or scroll or leafy, triglyphs or continuous band. Even if the building is a 19th-century bank rather than a temple, you are reading a visual quote from Greece. And that, quietly, is exactly the kind of fluency we are building together.