Mycenaean Architecture: Megaron, Citadel and Cyclopean Walls

The soaring corbelled vault of the so-called Treasury of Atreus shows how Mycenaean builders could create monumentally scaled interior space long before true arches.

Climb toward a Mycenaean hilltop and the building does something to you before you even reach it. The path narrows, the slope steepens, the walls rise on either side. Ahead, a stone gate closes the horizon, crowned with carved lions. Behind that gate, somewhere higher up, a smoky hall with a central hearth waits.

This is how Mycenaean architecture works. It is not just “old stone.” It is a deliberate way of turning hills into citadels, of wrapping power in walls and staging access to a ruler’s hall. In this explainer we will walk the basic kit: the citadel as a whole, the megaron hall at its core, and the famous Cyclopean walls that later Greeks thought only giants could build.

If you want a parallel view of the people living inside these spaces, you can pair this with our guide to who the Mycenaeans were, where we follow the society, graves and hero-myths behind the stone.

Mycenaean architecture turns hilltops into controlled citadels

A good starting point is the citadel at Mycenae itself. The site sits on a rocky hill with strong natural slopes on several sides. Mycenaean builders do not level it into a neat platform. Instead they wrap it in Cyclopean walls and use the uneven terrain. Ramps, terraces and gates guide anyone entering along specific paths.

Inside the walls, the citadel is not one clean rectangle. It is a cluster of spaces: the palace complex, storage areas, workshops, smaller houses, water access and, just outside or nearby, monumental tombs. The whole thing is a compact town plus palace, but with a clear internal hierarchy. The higher you climb, the closer you get to the main hall and to the people who control it.

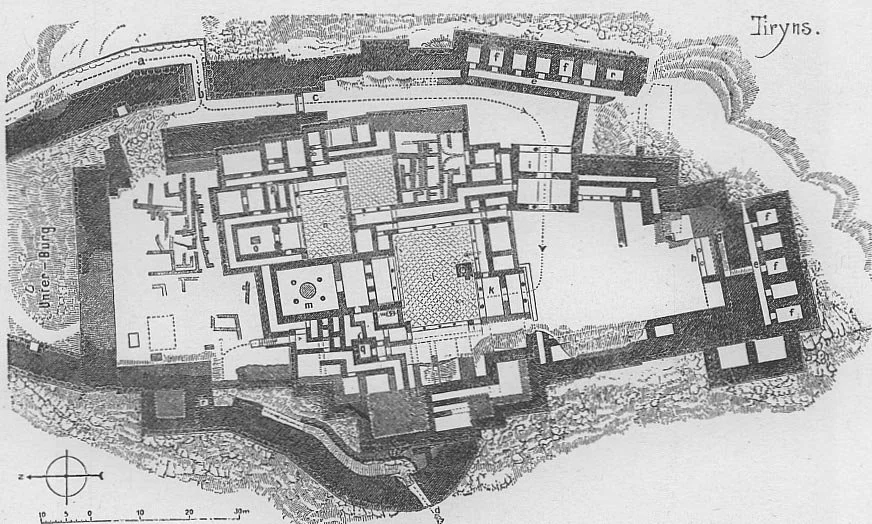

Other Mycenaean centres follow a similar pattern. At Tiryns, a lower hill near the Argolic Gulf, the Mycenaean ruins show massive encircling walls, an upper and lower citadel and a palace with its own megaron. At Pylos, on the west coast, the palace rises above coastal plains and harbours. The fortifications there are lighter than at Mycenae or Tiryns, but the idea is still the same: a controlled, elevated core that dominates its surroundings.

Seen from outside, Mycenaean architecture is known for its bulk. Seen from inside, it is about choreography. Ramps make you slow down. Narrow gates squeeze you. Courtyards and terraces open suddenly and let you breathe. The architecture is not neutral. It is constantly saying: “Here you stop. Here you wait. Here you look up.” That is part of how power feels, long before anyone speaks.

Only the stone foundations of the Mycenaean megaron survive, but its central hearth and axial layout became key models for later Greek temple design.

The megaron hall is a compact prototype for later Greek temples

At the heart of most palaces lies the Mycenaean megaron, a great hall that works like a control room for both ritual and politics. It is usually laid out as a sequence of spaces on a main axis: a porch with two columns, an anteroom, then the main hall with a central hearth and four columns around it. A throne stands along one side wall.

Architecturally, this is clever. The porch and anteroom create a kind of filter: you do not walk straight from the courtyard into the ruler’s presence. Each doorway narrows the group. The central hall then opens again around the hearth. Columns support the roof and may have framed a smoke hole above the fire. Wall paintings and decorated floors turn the space into a visual statement. At Pylos, for example, frescoes show griffins flanking the throne area, signalling that the person sitting there is not just a bureaucrat but someone touched by the divine.

If you want to go deep into this plan type, our separate explainer on what a megaron is breaks down entrances, columns, hearth and later influence. For this article, the key point is that the megaron is a spatial diagram of hierarchy. Few people reach it; those who do are immediately placed in a circle of light and heat, facing the throne.

This layout matters for later Greek architecture. Many scholars see the megaron as one of the ancestors of the Greek temple cella: a rectangular, fronted room with a strong axial approach. Later temples will rotate the focus from a human ruler on a throne to a cult statue of a god, and add colonnades all around, but the basic move – front porch, inner room, central focal point – is already here. Mycenaean architecture is not just an end; it is a starting sketch for what classical Greek stone temples will do.

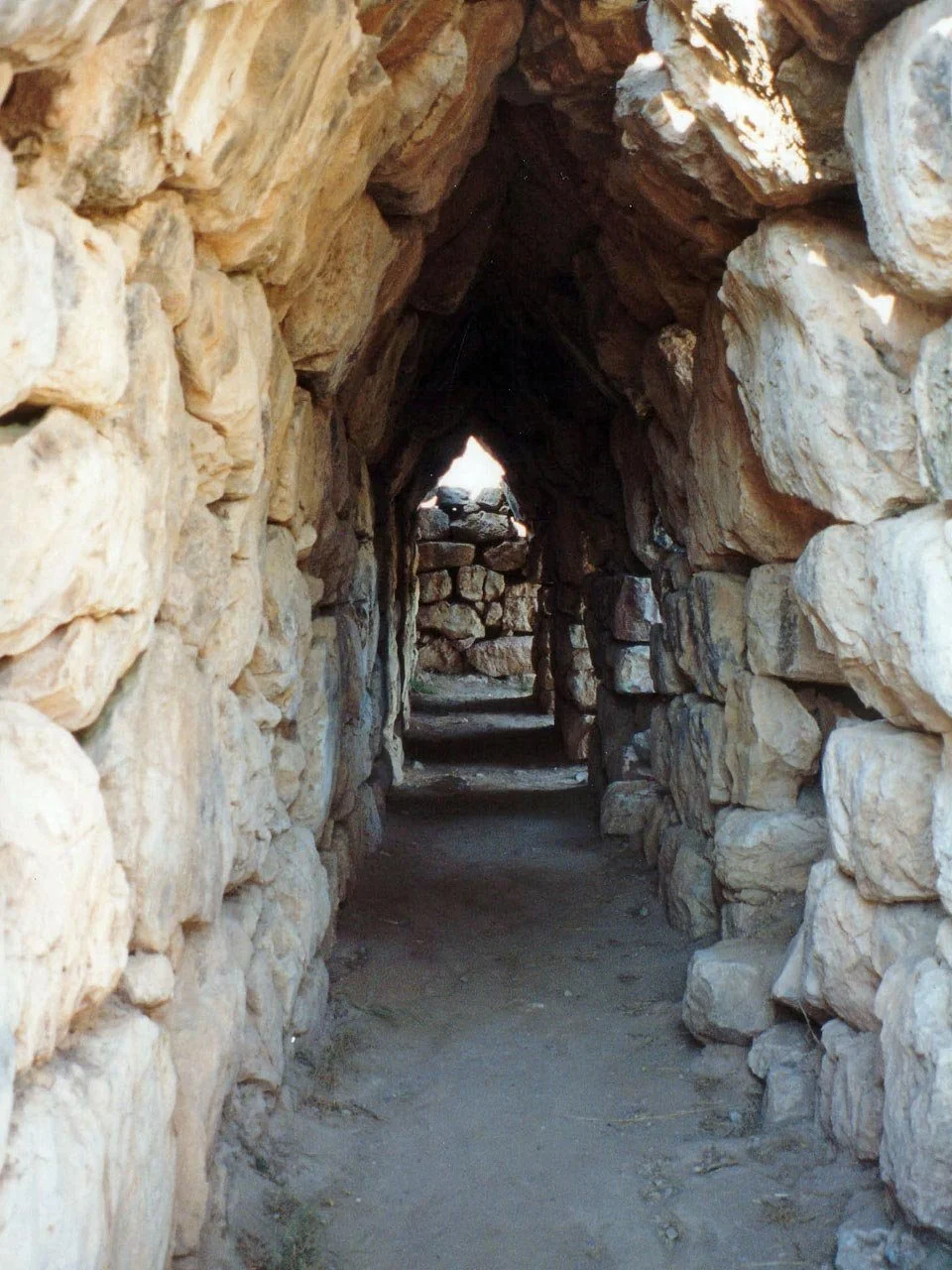

These narrow galleries, hidden within Tiryns’ massive walls, show how Mycenaean engineers thickened their defences while creating protected circulation routes.

Cyclopean walls and gates project power, fear and stories

If you ask a visitor what they remember most from a Mycenaean site, they will often say “those giant stones.” Cyclopean walls are made from huge, irregular limestone blocks, roughly fitted, with smaller stones packing the gaps. There is no visible mortar. At Mycenae and Tiryns, these walls can be several metres thick and rise up to around 10–13 metres in places. Ancient Greeks later called them “Cyclopean” because they believed only the Cyclopes, mythical one-eyed giants, could have moved such masses.

From a practical point of view, these walls are serious fortifications. They protect only the citadel, not the whole surrounding settlement, which suggests that in times of danger the population could retreat into the core. At Tiryns, corbelled tunnels run within the thickness of the walls, perhaps as storage or protected passage. At Mycenae, the wall bends to create flanking positions and to integrate earlier graves into the protected area.

The gates are points where architecture and image fuse. The Lion Gate at Mycenae is the most famous. It combines a narrow stone passage with a relieving triangle above the lintel, filled by a carved panel: two lion bodies facing a central column, their paws resting on an altar-like base. The composition sets up a visual equation: lions, column and gate belong together as symbols of strength and protection. Anyone entering passes under their gaze.

Other entrances use similar tricks without sculpture. Long ramps with high walls create “kill zones” where attackers would be exposed from above. Side postern gates offer hidden exits or flanking routes. Together, walls and gates broadcast a message both to locals and outsiders: this community can mobilise labour and defend itself. Even if there were long periods of peace, the stone keeps the idea of war readiness constantly visible.

Myth vs Fact

Myth: Mycenaean Cyclopean walls were literally built by giants from myth.

Fact: The walls were constructed by human engineers using massive limestone blocks; later Greeks invented the Cyclops story to explain their extraordinary scale.

The plan of Tiryns reveals a compact palatial core wrapped in heavy defences, helping us visualise how architecture, power, and security were tightly linked.

Mycenaean ruins as a blueprint and a warning for later Greece

So what happens to this architectural system after the palaces fall. When the Mycenaean world collapses around 1200–1100 BCE, many citadels are damaged, abandoned or reused at a smaller scale. Writing disappears for a time. Large central halls are no longer rebuilt in the same way. Yet the Mycenaean ruins stay on the landscape.

By the time of classical Greece, people can still see the Cyclopean walls and the outlines of citadels. They weave them into stories. Mycenae becomes the home of Agamemnon in epic. Tiryns belongs to Heracles. The sheer presence of the architecture demands explanation. The idea that “our ancestors” or semi-divine heroes built in a bigger, rougher style becomes part of how Greeks think about their own past.

At the same time, some architectural ideas quietly survive. Smaller megaron-type halls exist in early Iron Age sites. Temple builders of the Archaic period use stone to formalise certain relationships already present in Mycenaean plans: front porches, axial approaches, emphasis on the long rectangle as a sacred or civic space. You can see the citadel hill as a distant cousin of the later acropolis, and the megaron as a cousin of the temple naos.

When you next look at a reconstruction of the citadel at Mycenae, it is worth keeping both scales in mind. On one hand, this is a specific Late Bronze Age fortress, with its own politics, economy and local landscape. On the other, it is one of the early experiments in using architecture to create a multi-level, symbol-heavy centre that later Greek cities will echo, simplify or react against.

Conclusion

My favourite way to think about Mycenaean architecture is to imagine walking it twice. The first time, you experience it like a Late Bronze Age visitor: climbing ramps, passing the Lion Gate, entering the megaron with its hearth and painted walls, feeling the weight of stone and ceremony pressing in. The second time, you trace the same path with a floor plan and a pencil, noticing how each turn, each narrowing and each opening helps build a hierarchy of spaces.

What we have seen is that Mycenaean builders are not just stacking big stones because they can. They are using citadels, megaron halls and Cyclopean walls to do three things at once: defend, impress and organise. Hilltops become citadels, citadels frame megaron halls, and walls tell stories even to people who never enter the palace. Later Greek architecture will remember some of these tricks and forget others, but the basic idea – that architecture can stage power long before a word is spoken – is already here.

For our wider journey through the Aegean, this topic is a good hinge. On one side, softer Minoan palaces; on the other, the regular temples and civic buildings of classical Greece. In between, these steep, rough citadels that feel half-ruin, half-prototype. If this guide helps you see Mycenaean architecture as more than “old stone,” and instead as a thought-out system of space, fear and prestige, then you are ready to zoom in further on single elements like the megaron, the gate, or the citadel as a whole. Each one is a chapter in how built space becomes political.

Sources and Further Reading

UNESCO World Heritage Centre — “Archaeological Sites of Mycenae and Tiryns” (1999) (Centro Patrimonio Mondiale dell'UNESCO)

Greek UNESCO Monuments — “Archaeological Sites of Mycenae and Tiryns” (n.d.) (Greek Unesco Monuments)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art — “Mycenaean Civilization” (Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, 2003) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Smarthistory — “Mycenaean art, an introduction” (2020) (Smarthistory)

Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports — “Mycenae Archaeological Site” (n.d.) (odysseus.culture.gr)

Pressbooks (Art and Visual Culture: Prehistory to Renaissance) — “Mycenaean Art Lesson” (2019) (pressbooks.bccampus.ca)