Ancient Greek Paintings: The Few Images That Survived

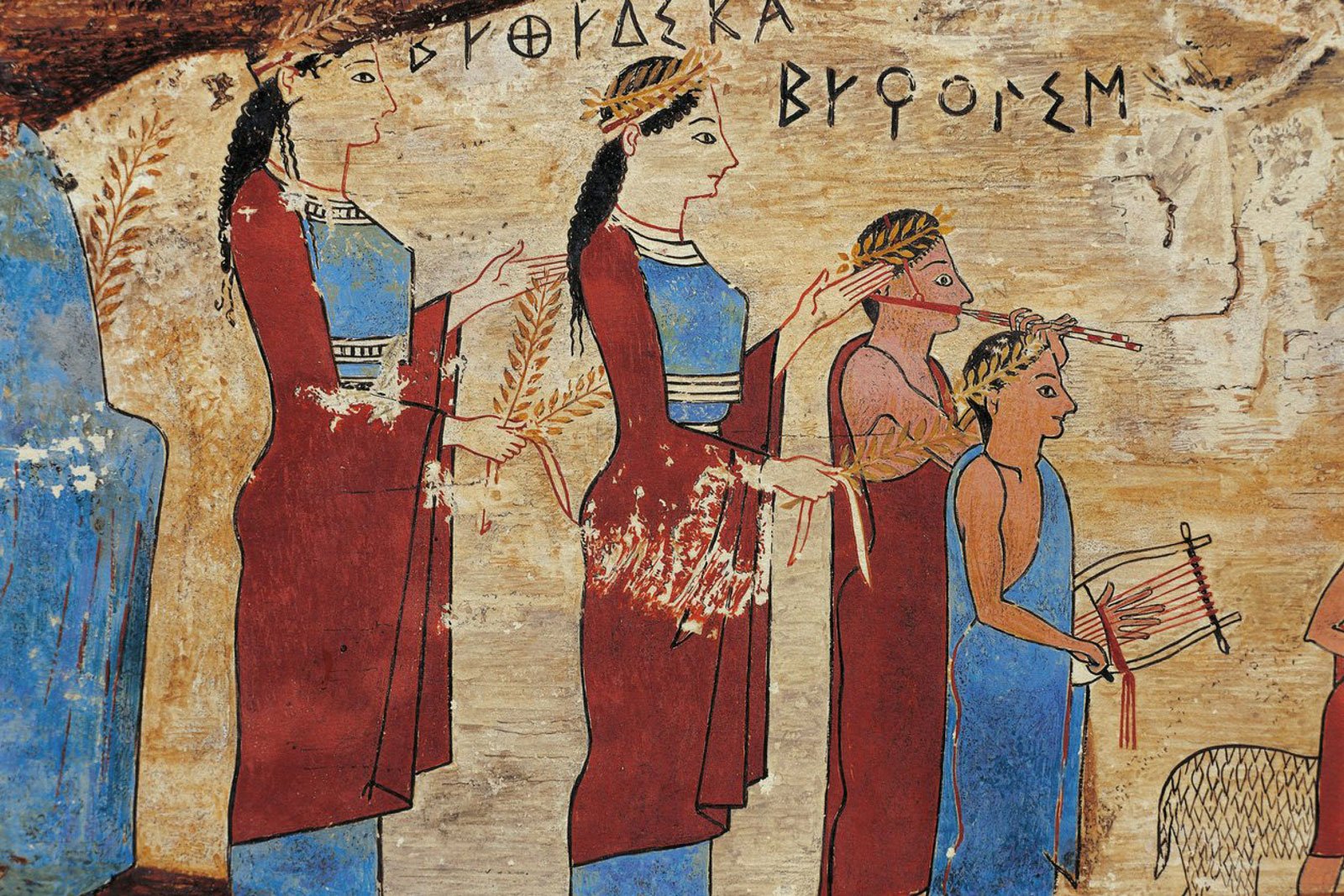

The painted Pitsa panel is a rare survival of Greek panel painting, capturing a rural festival with women, children and music in story-book color.

When we think of ancient Greek art, we usually think in stone: temples, statues, columns. But Greek writers were obsessed with painters. They praised illusionistic images, shimmering colours, even stories of birds pecking at painted grapes because they looked so real. The frustrating twist is that almost none of those paintings survive.

In this guide, we go treasure-hunting. We collect the few ancient Greek paintings that did make it through – on walls, on small panels, inside tombs – and ask what these scraps tell us about a vast “lost” tradition. Along the way, we keep linking back to the better preserved world of Greek pottery and Greek vases, because much of what we know about Greek painting now comes from these more durable surfaces.

Definition

Ancient Greek painting is figural or decorative imagery made with pigments on walls, panels, stone or pottery in Greek cultural contexts.

Most ancient Greek paintings are lost, so we learn from rare survivors

The blunt truth is that the Greeks’ favourite painting supports were perishable. Literary sources tell us that the most prestigious works were panel paintings on wood, often covered with a light ground and worked up with mineral pigments and binders. Wood, canvas and thin plaster layers do not love time, earthquakes or damp churches. As a result, almost none of the masterpieces praised by ancient authors are still around. Harvard Art Museums summarise this problem clearly: we have names, anecdotes and rivalry stories for Greek painters, but not a single secure wall or panel painting by them survives.

What we do have are protected exceptions. Paintings that happened to be sealed in tombs, covered by later building phases or executed on more durable stone backgrounds. A Met essay on Hellenistic painted funerary monuments points out that our understanding of Greek painting techniques now relies heavily on images preserved in unusual, sheltered conditions, like Macedonian chamber tombs or niche slabs from Alexandria.

Because of this, most modern overviews of ancient Greek art take a hybrid route. They combine:

Direct study of the few surviving wall and panel paintings.

Close reading of painted pottery, especially Greek black-figure pottery and later red-figure.

Literary descriptions of lost works.

Roman copies and adaptations, especially for later classical and Hellenistic styles.

For us as learners, that means accepting two things at once. First, we cannot point to a neat, continuous gallery of Greek painting in the way we can for sculpture or architecture. Second, the scattered pieces we do have are incredibly rich when we give them time and context.

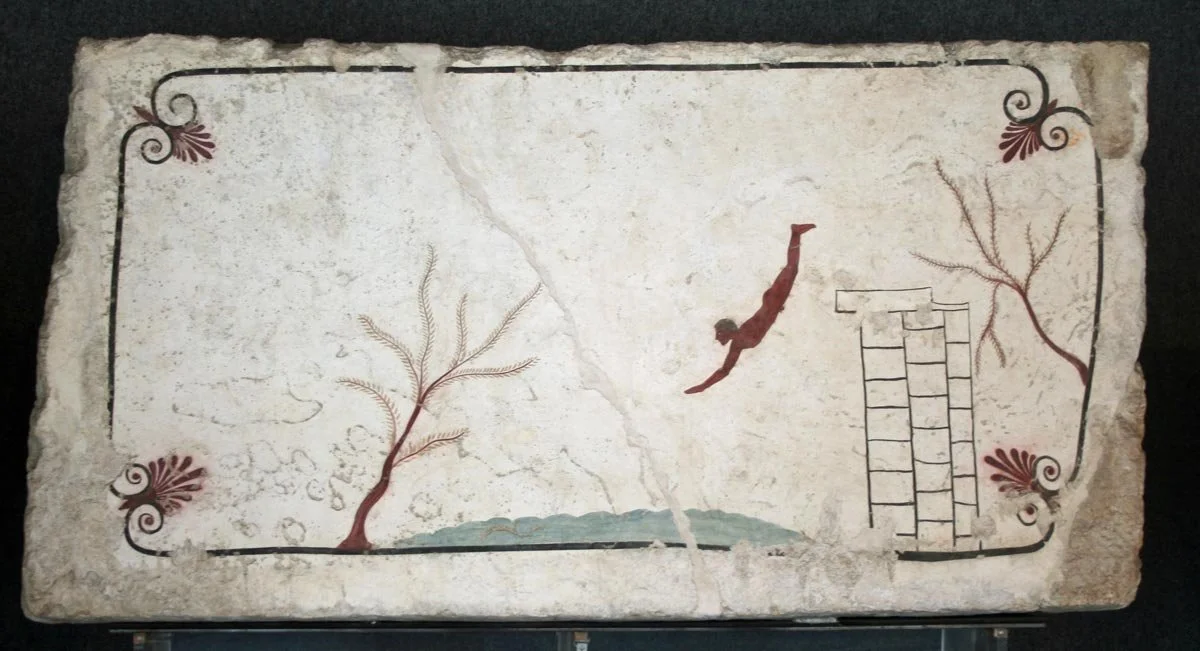

Frescoes from the Tomb of the Diver at Paestum, balancing a solitary plunge into water with lively banqueting scenes around the walls.

Pitsa panels and the Tomb of the Diver: tiny windows into Greek colour

A good way into surviving Greek paintings is to start with two famous cases: the Pitsa panels and the Tomb of the Diver. They are small and unusual, but they carry important clues about colour, line and subject matter.

The Pitsa panels are a group of wooden tablets from near Corinth, dated to the later 6th century BCE. They are coated in a light plaster and painted with mineral pigments in bright, flat areas of blue, red, yellow, green, white and black. Art historians call them the oldest surviving Greek panel paintings. Technical and stylistic studies show that outlines were probably laid in first, then filled with solid colour, with almost no shading. The scenes seem to show processions and sacrifices to nymphs, so religious rituals rather than myths or portraits.

The Tomb of the Diver at Paestum, in southern Italy, is a small stone burial chamber dated around 470 BCE. Its interior slabs are covered with frescoes: symposion scenes on the walls and, on the ceiling, the famous diver leaping into a band of water between two stylised trees. Scholars describe it as the only fully preserved Greek figured wall painting from the Archaic or early Classical periods.

In both cases, what strikes many visitors first is the colour. We are so used to seeing Greek art in bare stone that these panels and tomb walls feel almost shocking: flat blues and reds, dark outlines, patterned borders. They sit surprisingly close to the colour logic of Aegean works like Minoan bull-leaping, even though centuries separate them. Technical analyses of the Paestum tombs show rich, layered use of lime-based plasters and mineral pigments, confirming that Greek painters had solid control over fresco-like methods.

If we link these fragments back to the painted surfaces of Greek pottery, a picture begins to form. Strong outlines, flat but carefully chosen colours, and patterned edges seem to be shared habits, adapted differently for clay, stone and wood.

Mini-FAQ

Q: What are the most important surviving Greek paintings?

A: Key examples include the Pitsa panel tablets, the frescoes of the Tomb of the Diver at Paestum, and painted funerary monuments from Macedonian and Hellenistic tombs.

Wall painting in tombs and sanctuaries: what Hellenistic examples add

Moving forward in time, more Greek wall paintings survive from the late Classical and Hellenistic periods, especially in Macedonia, Alexandria and South Italy. They are still a small sample, but they let us see more ambitious compositions and technical tricks.

Macedonian tombs near Vergina and elsewhere preserve frescoes of hunts, chariot scenes and large, almost life size figures. Their colours are more nuanced, with attempts at shading and modelling. Hellenistic Alexandria gives us painted funerary stelae: upright slabs with recessed painted panels showing the deceased in domestic or civic poses, sometimes with horses or servants. The Met’s essay on these monuments stresses how such images project social status and identity into the afterlife, blending painting with the language of sculpture and inscription.

In South Italy, Paestum again offers a cluster of painted tombs beyond the Tomb of the Diver, with banquet and procession scenes. Recent archaeometric work compares pigments and techniques across these tombs, highlighting shared workshop practices and specific choices for backgrounds, outlines and garment colours.

These wall paintings matter for two big reasons:

Space and depth. They show Greek artists experimenting with architectural backdrops, landscape elements and overlapping figures, not just flat friezes. Even if full linear perspective is not in play yet, there is a clear interest in building pictorial space.

Interaction with religion and ritual. Most surviving examples are funerary, which ties them closely to ancient Greek religion. Scenes of banquets, farewells or heroised dead suggest that painting played a role in visualising the afterlife, family memory and the status of the deceased.

If we place these works next to earlier Aegean wall programs in spaces like the megaron, and later Roman house paintings, we can start to sketch a long, if broken, history of Mediterranean mural traditions. Greek painting sits right in the middle of that chain, even if its examples are rare.

Slab from the Tomb of the Diver at Paestum, where a single diver plunges into water as a metaphor for crossing worlds.

Using vases and texts to imagine the painting tradition we lost

Because the record for ancient Greek wall painting and panel work is so thin, historians lean heavily on two other bodies of evidence: painted vases and ancient texts.

First, pottery. As we saw in Greek black-figure pottery and Greek vases, ceramic painters spent centuries solving problems of bodies in motion, overlapping figures, foreshortening and narrative structure on curved surfaces. A library guide from the Nelson-Atkins Museum notes that much of what we know about Greek painting – composition types, costume, gesture, even attempts at depth – comes from carefully studying vase imagery, since so many wall and panel works are gone.

Second, literature. Authors like Pliny the Elder preserve stories about famous Greek painters, their innovations and their rivalries: who invented shading, who first painted figures seen from behind, who could fool birds with their grapes. While these anecdotes are not neutral, they confirm that technical concerns like illusionism, colour mixing and atmosphere were central to Greek painting discourse. Combined with the limited surviving works, they suggest a spectrum from flat, decorative styles to more experimental ones that push toward three dimensional effects.

Roman copies complicate things further. Many wall paintings in Pompeii and elsewhere clearly reference Greek myth scenes and compositional formulas. Roman collectors also chased Greek panel paintings aggressively. Smarthistory’s discussions of Roman copies of Greek art point out that, in some cases, our mental image of “late Classical Greek painting” may be filtered through Roman reinterpretation, both in sculpture and in fresco.

So when we look at the few Greek painting examples that survived, it is helpful to see them as the visible tip of a huge, mostly submerged iceberg. Vases, texts and Roman works are not substitutes for lost originals, but they are important reflections. They let us ask sharper questions about what these handful of frescoes and panels are doing with colour, space and storytelling.

Conclusion

Ancient Greek paintings are, frustratingly, more absent than present. Yet even that absence taught us something. We saw how fragile materials and later building history erased most panel and wall works, leaving us with rare clusters like the Pitsa panels and the Tomb of the Diver, plus Hellenistic tomb and stele paintings. We watched these fragments light up a map that stretches from early religious processions to banquets in the afterlife, all saturated with unexpected colour.

We also made peace with the idea that to understand Greek painting, we have to think sideways. We turned to the painted surfaces of Greek pottery and Greek vases, to texts praising lost masters, and to later Roman adaptations. All of them, together, help us imagine the larger picture that once hung on sanctuary walls, palace rooms and public buildings, shaping how Greeks saw gods, heroes and themselves.

For me, the most useful habit here is to treat every painted trace – a small panel, a tomb ceiling, a figure on a vase – as part of a much bigger, broken fresco. If you connect this article with our broader overview of ancient Greek art and our zoom-ins on Greek paintings and Aegean murals like Minoan bull-leaping, the fragments start to talk to each other. The “lost art” of Greek painting will still be mostly invisible, but it will feel less like an empty hole and more like a carefully reconstructed, if incomplete, room.

Sources and Further Reading

Smarthistory — “Guide to Ancient Greek Art” (online book, 2019)

Smarthistory — “Ancient Greece, an introduction” (chapter on art and visual culture, 2015)

American Journal of Archaeology — “The Tomb of the Diver” (article, 2006)

WikiArt — “Ancient Greek Art” (overview of ancient Greek painting and sculpture, 2010s)