The First Dynasty of Egypt: a Complete Framework

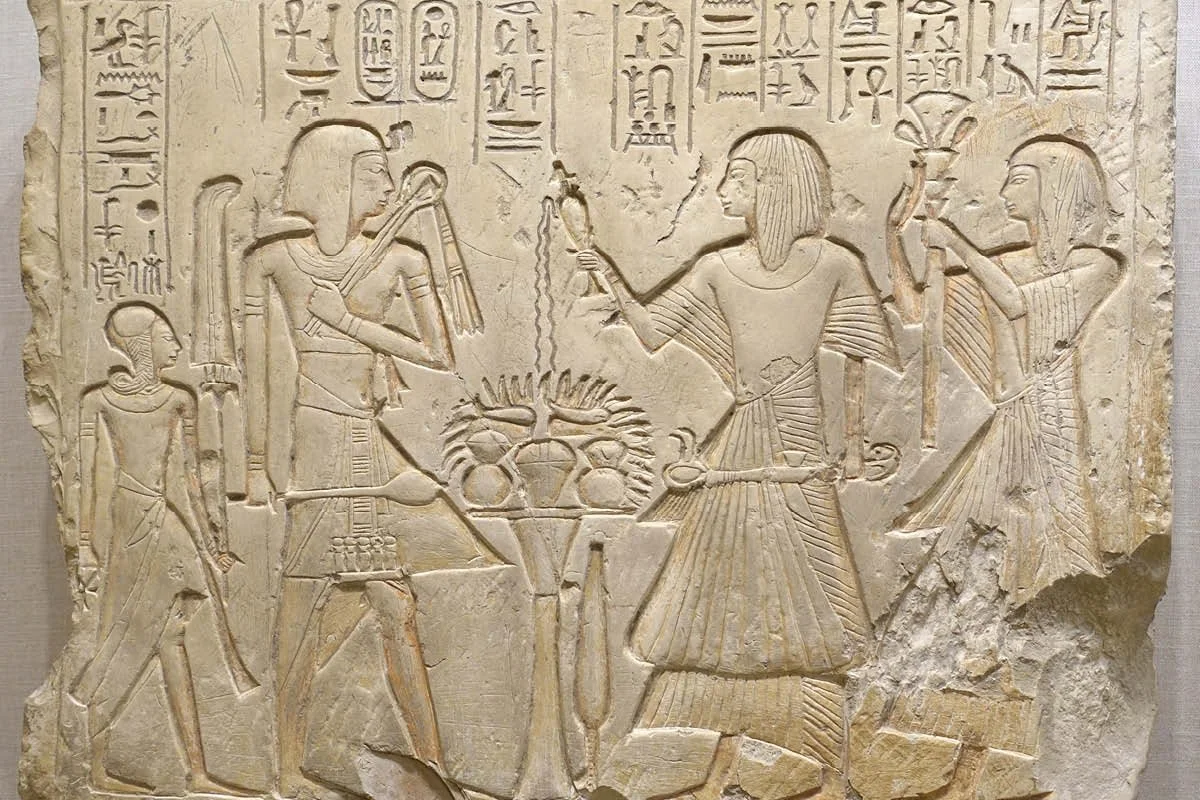

Relief of Seti I with the young Ramesses II, Dynasty 19 (c. 1294–1279 BCE), New Kingdom.

We hear “First Dynasty” and it feels like a label on a timeline. Let’s make it a place, a set of people, and a handful of objects you can actually picture. In this period, kingship becomes a system: names are formalized, tombs scale up at Abydos, and administrative life gathers in the north near the future capital of Memphis. If we read the evidence—palettes, sealings, tomb plans—Egypt’s first rulers stop being a list and start feeling like a state taking shape. For broader background on sacred and civic space, keep our overview of ancient Egyptian architecture handy.

Definition

First Dynasty of Egypt: the earliest line of pharaohs after political unification, when royal names, rituals, and administration solidify.

What counts as “First Dynasty,” and what evidence do we trust?

We’re talking roughly c. 3000–2890 BCE (give or take a few decades; early dates are elastic). Names you’ll meet include Narmer, Aha, Djer, Djet, Den, Anedjib, Semerkhet, and Qa’a. The key is not memorizing the sequence but seeing what changes across their reigns. We move from symbolic records (like the Narmer Palette) to administrative sealings and labels that show storage, taxation, and provisioning. We see royal names enclosed in a serekh (a palace-façade frame topped by Horus), an early device that fixes the king’s public identity.

Archaeology anchors the story. At Abydos, royal tombs in the Umm el-Qaab cemetery reveal increasing scale, better carpentry and masonry, and more elaborate subsidiary burials in the earliest reigns (a practice that later fades). In the north, near the future city cluster of Memphis, large mastabas (bench-like tombs with rooms and a shaft) experiment with brick types, wooden roofs, and early stone. Put simply: kingship grows more visible in burial, and administration grows more visible in storage and sealing. Those two tracks—ritual and logistics—are what make a state.

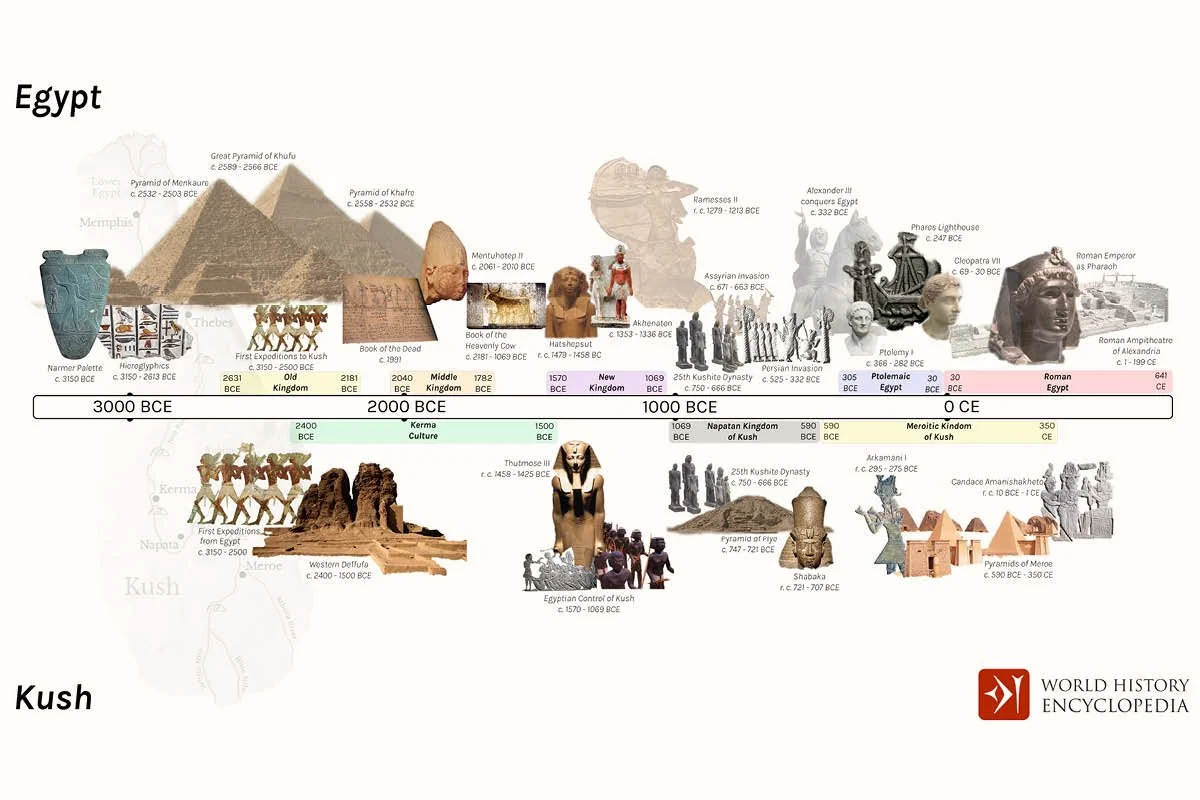

Comparative timeline of ancient Egypt and Kush showing major dynasties and monuments. Source: World History Encyclopedia

Abydos: where kingship becomes a ritual machine

Why Abydos? Because ancestral presence mattered, and the desert edge at Umm el-Qaab offered clean ground, good building sand, and a route for processions. Royal tombs evolve from deep shafts and wooden chambers to more complex compounds with funerary enclosures closer to the valley. In one generation you can watch builders test brick bonding, improve timber ceilings, and expand storage rooms for offerings and equipment. Pottery types, jar sealings, and stone vessel sets repeat in patterns that look like state provisioning, not family burial.

The message carved into the landscape is simple and loud: the king’s death is a public rite. Processions moved from the cultivation fringe toward the tombs, and the architecture enforced that movement. This choreography is the seed of later practice. When we eventually stand at the Temple of Hatshepsut or walk the great court at Edfu, we’re seeing a matured version of a path that was already taking shape in the First Dynasty: from public presence to sacred core, step by step.

Memphis and the north: where administration learns to breathe

While Abydos handles royal memory, the north handles management. The location near the Delta meant access to grain, river routes, and labor pools—perfect for a seat of power. Even if the earliest palaces are lost to later building and Nile shifts, the archaeological footprint of administration survives in storage facilities, seal impressions, and high-status tombs aligned with orderly courtyard-and-room plans. The mastabas around the low desert near early Memphis show standardization: repeated proportions, similar storage rooms, consistent use of mudbrick and timber, and early experiments with stone fittings.

Why does this matter? Because states live or die by inventory. The First Dynasty’s sealed jars, jar-labels, and serekhs on crates tell us in plain terms that officials tracked goods, corvée labor, and offerings at scale. The architecture follows: rooms for counting, spaces for keeping, and walls that filter access. It’s the same logic you’ll later feel in the serialized magazines of a temple complex. If you picture the map of ancient Egypt, Memphis sits where river arms and desert roads meet—a choke point turned into a capital.

Temple of Seti I at Abydos, showing detailed reliefs and traces of original pigments.

Objects that define the era: palettes, labels, and seals

A few object types are your fast track into the First Dynasty:

Palettes (like Narmer’s): once cosmetic tools, now ceremonial records that fold myth and politics into one showpiece. You’ll see processions, standards, and smiting scenes packed into tight registers.

Sealings and jar labels: tiny, repeatable artifacts that prove storage and distribution. A roll seal across a jar stopper is a snapshot of an office doing its job.

Stone vessels: sets in hard stones that show workshop flow and court taste; they move with elites between Abydos, the north, and the Delta.

Early stone fittings: door jambs, thresholds, and stelae that announce names and offices—an incremental step toward the all-stone confidence of the Old Kingdom.

The trick is to read these objects as systems evidence, not isolated masterpieces. A palette is a message to an audience; a jar label is a message to a storeroom. Together, they map a government without needing a chronicle.

What the First Dynasty sets in motion

By the dynasty’s end, three habits are locked in:

Named kingship that broadcasts itself clearly—serekh, Horus name, ritual program.

Dual geography of power—ritual anchored at Abydos, administration concentrated in the north.

Architecture as sequence—the sense that routes, courtyards, and thresholds organize people and meaning.

Those habits are the bedrock of later monuments. When we look at the Pyramids of Giza site plan or the inside logic of Khufu’s pyramid (pair it with Great Pyramid facts and Inside the pyramid), we’re seeing a First Dynasty mindset scaled to stone mountains: names, routes, storage, and a core room that must endure.

Mini-FAQ

Was Narmer the first king of the First Dynasty?

He is often placed at the threshold; some lists start with Narmer, others with Aha. The safer takeaway is continuity across the unification moment rather than a single “founder.”

Why do scholars split attention between Abydos and Memphis?

Because burial ritual and state administration grow in different landscapes: Abydos fixes royal memory; the Memphis region concentrates day-to-day control.

Conclusion: a dynasty you can picture

Treat the First Dynasty as a working model, not a misty origin. At Abydos, royal tombs and enclosures test how the state remembers and stages itself. Near Memphis, mastabas and sealings show how goods and people were counted, moved, and taxed. Objects—palettes, labels, seals—tie the two worlds together. Once you see those moving parts, the First Dynasty becomes exactly what you wanted from a framework: clear, concrete, and connected to everything that follows.