Greek Black-Figure Pottery: How Greeks Painted in Silhouette

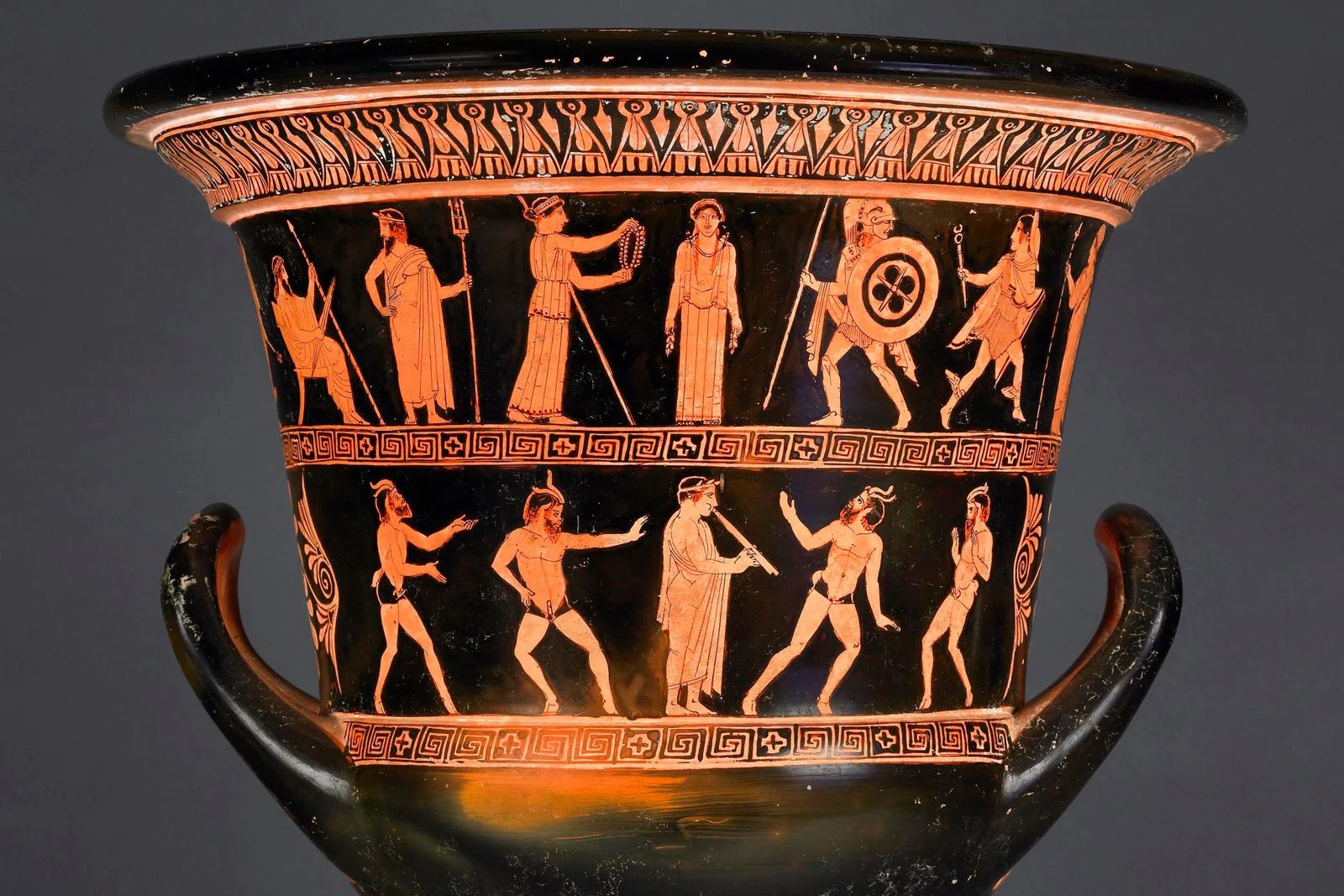

Red-figure kraters like this framed storytelling at the symposium, where drinkers passed myths, heroes and dancers around the table with the wine.

If you picture a “Greek vase”, chances are you are seeing black-figure without knowing it: orange clay, ink-dark figures in profile, tiny details scratched into the surface. It looks simple at first, like a silhouette game. Then you realise how much story, anatomy and pattern those painters squeezed into a very restricted toolbox.

In this guide, we zoom in on Greek black-figure pottery as a technique and as a way of thinking about images. We will walk through how it works on a technical level, what scenes artists loved, and why another method – red-figure – eventually takes over. If you want the broader context, you can keep our overviews of Greek pottery and Greek vases open alongside this one.

Definition

Greek black-figure pottery is a vase painting technique where dark, glossy figures are painted on red clay and then incised with fine details before firing.

Black-figure pottery turns silhouettes into sharp, graphic stories

Black-figure is one of the big two techniques of Greek vase painting, along with red-figure. It appears around the late eighth to early seventh century BCE and dominates much of the sixth century. For a while, if you were buying a decorated Athenian pot, chances were very high you were buying black-figure.

The basic look is quite strict. Artists paint figures and ornaments in a glossy slip that will fire black, leaving the background as the natural orange of the clay. Before the pot goes in the kiln, they scratch into that black layer with sharp tools, carving out hair, muscles, folds of cloth and patterns as fine light lines. They sometimes add white or purplish-red details on top for highlights, like women’s skin, horse manes or parts of armour. The result is a strong contrast: dark blocks for bodies, cut with crisp incised drawing.

At first, Corinth seems to lead the way, then Athens picks up and pushes the style to its peak. Workshops experiment with scale, from tiny perfume flasks to huge story-crammed kraters, and with how many figures they can fit around an amphora-type vase without losing legibility. We talk more about those underlying shapes in our focused guide to the amphora vase.

The important mental shift is this: black-figure is not a “primitive” step on the way to red-figure. It is a deliberate graphic language. Painters choose it because silhouettes plus incision give them a particular kind of clarity and rhythm, especially for armour, patterned cloaks and animal bodies. Once you start seeing it that way, the style feels less like an old format and more like an artistic choice.

Mini-FAQ

Q: What is Greek black-figure pottery?

A: It is a vase painting technique where black silhouettes with incised details decorate the red clay surface of a pot.

How the black-figure technique actually worked

To understand why black-figure looks the way it does, it helps to walk through the making process. In a way, every pot is a layered technical performance.

First comes the clay. Athenian potters use fine, iron rich clay that fires to a warm reddish colour. They shape vessels on the wheel, add necks and handles, then let everything dry to the right stage. At this point, the surface is smooth but still can accept paint.

Then the painter steps in with a refined clay slip. This is not paint in the modern sense. It is a carefully prepared liquid clay that, thanks to its composition and firing, will turn glossy and dark. The painter uses it to block in figures and ornament as flat shapes: bodies, shields, horses, borders. At this stage, the scene looks like pure silhouette.

Once the slip dries, the painter (or a specialist assistant) uses sharp tools to incise interior lines. This is where muscles, fingers, hair and patterns appear. Scratching cuts through the black slip back to the orange clay beneath, so each incision shows as a thin light line. White and red details can be added with thicker mixtures to mark things like women’s flesh or decorative bands.

The real magic happens in the kiln. Black-figure relies on a three-stage firing process: oxidising (lots of oxygen, everything turns red), reducing (limited oxygen, everything turns black) and re-oxidising (oxygen returns, the unslipped clay turns back to red, but the sintered slip stays black and glossy). This cycling is what fixes the famous orange-and-black contrast. Experimental reconstructions and technical essays show just how carefully potters had to manage temperature and airflow to get consistent results.

When you see a well preserved black-figure scene, you are looking at the success of all those steps. A chipped or misfired pot shows what happens when one part of the chain fails. Keeping that process in mind makes the objects in Greek pottery feel less static and more like the outcome of a lab experiment shared across generations of artisans.

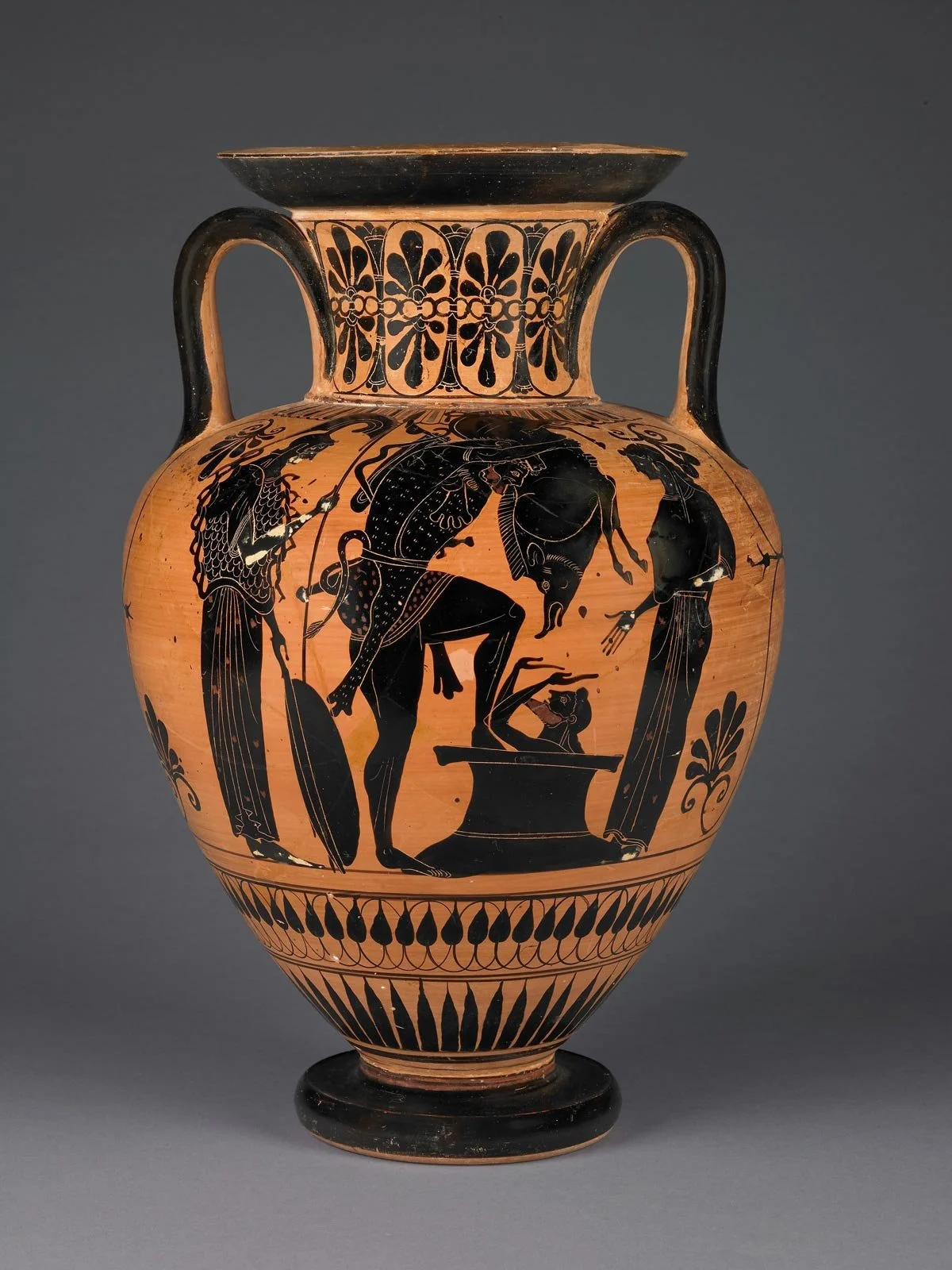

A powerful Leagros Group amphora, where overlapping warriors and shields pack mythic battle into a single swirling black silhouette.

What black-figure painters loved to show on their vases

Once the technique settles, Athenian black-figure painters quickly become obsessed storytellers. They crowd their silhouettes with myth, daily life and intricate patterns, all squeezed into the curve of a vessel.

Myth comes first in sheer quantity. Heroes like Herakles, Theseus and Achilles appear constantly, wrestling monsters or duelling in front of watching gods. Famous works such as the François Vase or Exekias’ amphora with Achilles and Ajax playing a board game stack multiple episodes or focus tightly on one charged moment. Even without knowing the names, you can often feel the drama: a spear about to strike, a chariot turning, a god stepping in. Overviews of vase painting stress that black-figure is one of our richest visual archives for Greek myth outside written texts.

Alongside myth, we see daily life: athletes training, men reclining at symposia, women at home preparing wool or managing funerary rituals. These scenes echo the domestic settings we reconstruct in ancient Greek houses and help us picture how vessels were actually used at the table or in rituals. Children’s resources and museum galleries on Greek paintings and ancient Greek paintings often lean on these vases precisely because they show such concrete gestures: lifting a krater, pouring from an oinochoe, carrying a hydria from the fountain.

Do not overlook the decorative bands. Meanders, tongues, lotus-and-palmette chains and other motifs break the surface into registers, mark transitions between scenes, and anchor figures to the curvature. In our article on Greek patterns we treat these as a design system in their own right. Black-figure pots are a great place to start spotting how patterns and pictures support each other.

Sometimes black-figure painters also nod back to older visual traditions, like the dynamic animal and acrobat scenes we see in Minoan bull-leaping. The precision of silhouettes and incised lines makes them especially good at capturing movement: horses mid gallop, dancers turning, warriors twisting in combat. That kinetic energy is part of why the style remained appreciated long after red-figure became the cutting-edge technique.

Dionysos, a music-making satyr and maenads circle this pot, turning its curved surface into a never-ending Dionysian procession.

Why red-figure replaces black-figure (and why black-figure still matters)

So if black-figure is so effective, why does red-figure take over? The short answer is control and subtlety.

Around the late sixth century BCE, Athenian workshops flip the logic: instead of painting the figures in black and incising details, they leave the figures in red clay and paint the background black. This red-figure technique lets artists draw interior lines with a brush rather than scratch them out, which means finer control over anatomy, drapery and overlapping poses. Oxford and Met essays emphasise that around 530 BCE red-figure quickly becomes the dominant high-end style, though black-figure continues in some formats.

For painters, red-figure is like switching from carving into a stencil to having a good pen. It becomes easier to show foreshortened limbs, three-quarter views and complex groupings of figures. This is crucial as Greek artists in the late Archaic and Classical periods push for more naturalistic bodies, the same broader trend we see in ancient Greek art. Black-figure can hint at volume and depth, but red-figure lets artists really model it.

That said, black-figure does not simply vanish. It remains in use for certain shapes, especially Panathenaic prize amphorae and some more “traditional” contexts, and continues to be exported and copied in other regions. Museums and research projects still devote entire catalogues to black-figure collections, and the Beazley Archive’s indexes of potters and painters show just how large and varied this body of work is.

For us as learners, black-figure is the perfect starting point for understanding Greek vase painting. Its silhouettes make scenes easy to read; its incised details reward close looking; and its long use across shapes documented in Greek vases ties it directly into questions of function and daily life. Once you are comfortable with it, stepping into red-figure and later painting feels much less intimidating.

Conclusion

Greek black-figure pottery can look, at first, like a limited style: black shapes on red clay, repeated over and over. Once we walked closer, the picture changed. We saw how potters and painters turned silhouettes plus incision into a highly controlled graphic language, supported by a demanding three-stage firing process. We traced the kinds of stories that language likes to tell: gods and heroes, athletes and symposia, women at work and at ritual, all wrapped around the forms you now know from Greek vases and the wider world of Greek pottery.

We also watched red-figure emerge, not as a total break, but as a reversal and refinement of the black-figure system that allowed even more subtle drawing. Black-figure prepares the ground technically and visually; red-figure picks up that groundwork and pushes it further. If you connect this article with our guides to ancient Greek paintings, Greek paintings and the older imagery of Minoan bull-leaping, you start to see a continuous thread of experimentation in how Greeks put stories on surfaces.

Next time you stand in front of a case of vases, try picking a single black-figure piece and doing the full reading: spot the silhouettes, trace the incised details, match the shape to its job, then imagine the pot back in use on a table, at a grave, or in a sanctuary. That small act of attention is what slowly turns museums from storage spaces into places where you and these stubborn, fired-clay stories are in real conversation.