How Ancient Egyptian Architecture Influenced Greece and Rome

Detail of the Roman amphitheatre at Kom El Dikka in Alexandria, 2nd–4th century CE.

Stand in front of a temple on the Nile and you feel two things at once: clarity and scale. Plans are straight. Gateways pull you forward. Courts flood with light; halls thicken into shadow; a tight sanctuary holds a polished stone shrine. That grammar—pylon, court, hypostyle, holy room—stayed persuasive for three thousand years. It also traveled. Greek and Roman builders didn’t copy Egypt block for block, but they borrowed techniques, symbols and city ideas. This guide maps the core Egyptian toolkit first, then shows how pieces of it echoed from the Aegean to Rome.

For orientation, keep the map of ancient Egypt close. Capitals like Memphis grew where river, routes and quarries met. Our Memphis site dossier zooms into that early landscape.

Definition

Hypostyle hall: a roofed space held by many columns, often dim and cool.

The Nile is the blueprint

Egyptian architecture starts with geography. The green floodplain was for living and making; the desert edge was for memory and gods. Cities hugged the river; cemeteries stepped onto dry ground. From that split came two toolkits: mudbrick for houses and walls, stone for temples and tombs. River transport let quarries far south feed building up north. Block size, column type, even courtyard width answer to sun, wind and water. When we read a plan at Saqqara or Thebes we are reading climate logic.

Zoom in on domestic space and you’ll see how comfort drove form. Thick walls, small high windows and an open courtyard kept homes cool. Our primer on ancient Egyptian houses shows why roofs doubled as summer bedrooms and work terraces. Walk west toward the cliffs and the grammar flips from comfort to permanence. That is where ancient Egyptian tombs anchor memory in bedrock.

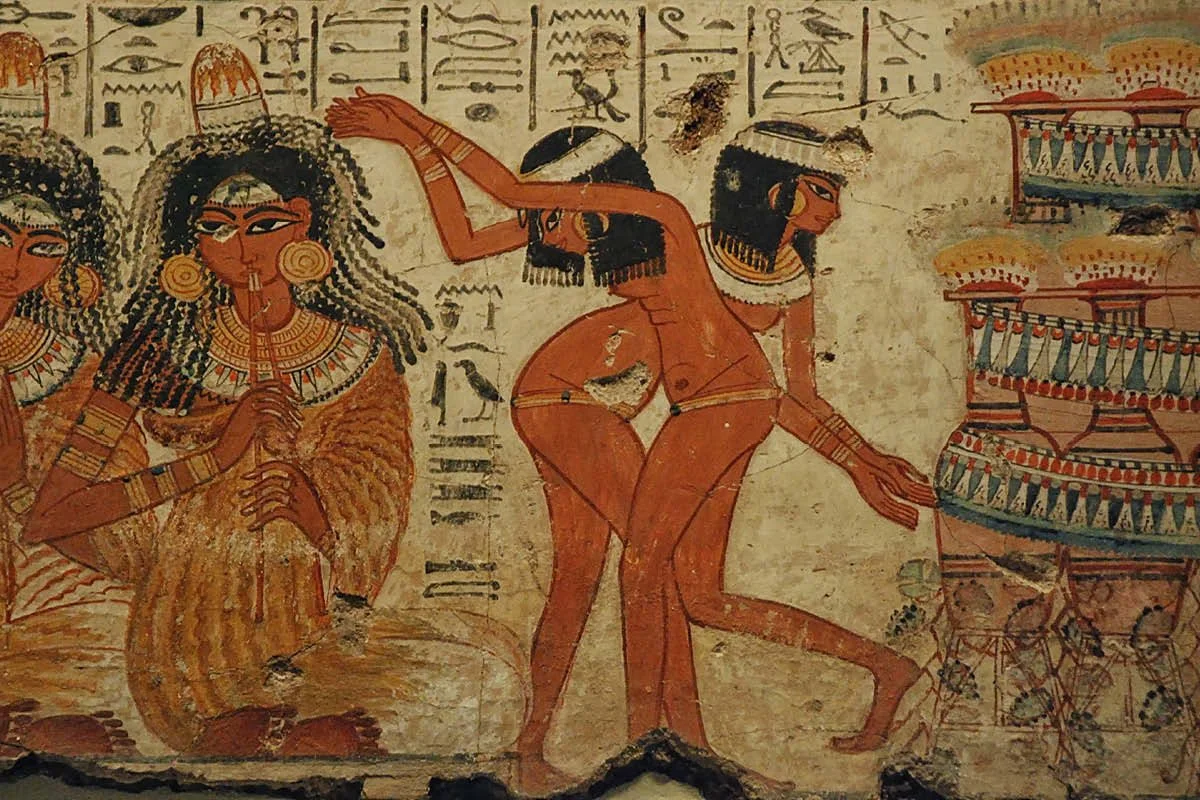

Musicians and dancers from a Theban tomb scene, New Kingdom (c. 14th–12th cent. BCE).

The temple grammar is a machine for movement

Egyptian temples guide you step by step. A pylon (tall battered gateway with a broad face) frames entry. A forecourt opens to sun and crowds. A hypostyle hall compresses space with columns like a stone forest. A sanctuary tightens around a naos (a small stone shrine for the god’s image). Along the edges, chapels and magazines serve ritual and storage. This sequence is not decorative. It moves a cult image on festival days, filters the public from the holy and stages the king’s role as servant of the gods.

You can walk this logic at Temple of Edfu, read its late, luminous version at Dendera, and feel it fold into water at Philae. The same rules choreograph cliffs at Hatshepsut’s terraces and mountains at Abu Simbel. Different sites, one playbook: bright to dim, open to close, crowd to core.

Definition

Cavetto cornice: a deep, concave molding crowning Egyptian walls and gates.

Materials and methods shaped what was possible

Most mass is limestone laid in courses. Where loads bite hardest, builders switch to hard stones like granite or sandstone. Columns carry plant forms—papyrus, lotus, palm—but their job is simple: roof a wide hall with stone beams. Surfaces take paint and low relief, brightening dim interiors and fixing texts to walls. On exteriors, the cavetto cornice and torus molding read from far away, sealing edges against weather and making a clear silhouette.

Scale rests on logistics. Quarries at Aswan and near modern Luxor fed obelisks and beams; barges moved monoliths on the Nile; ramps, levers and sledges on wet sand did close-up lifting. The same practical sense that kept houses cool kept ceilings safe. At Giza, for example, the Great Pyramid’s flat granite roof survives because it sits under relieving spaces—carefully placed voids that redirect weight. If that inside story intrigues you, read Great Pyramid facts and inside the pyramid. For the plateau as a whole, keep the Pyramids of Giza site plan open.

Papyrus-bundle columns with architrave, Luxor area, New Kingdom temple remains.

Tombs show invention as much as tradition

From mastabas (bench-like tombs with rooms and a shaft) to pyramids to rock-cut tombs, Egypt tuned form to meaning and site. Saqqara’s early step pyramid turns stacked mastabas into a new geometry. At Giza the pyramid becomes a smooth machine for procession and protection. In the New Kingdom, cliffs around Thebes hide royal burials while grand mortuary temples keep ritual visible on the floodplain. Hatshepsut’s temple stages its route in terraces. The desert road south ends in rock-cut theater at Abu Simbel, where colossi act as both façade and guardians.

The thread is not a single style. It is a habit of clear sequence, material honesty and site reading. Those habits are what travel best.

How ideas moved to the Aegean

Contact came in waves. Egyptians traded with the Levant; Greeks visited and later settled at Naukratis, a Greek trading city in the Western Delta. Travelers saw stone columns, axial gates, processional courts and a state that could quarry, move and set monoliths. Some of those impressions show up in Greek art fast—think of the kouros stance in sculpture. In architecture, the links are subtler but real in three areas:

Stone know-how at scale. The Greek turn from wood to marble involved seeing how to quarry, dress and lift stone in big pieces. Egypt offered an ancient manual.

Gateways and axes. The idea that a sacred complex begins with a bold frontality—a staged entrance that aligns processional space—parallels Greek propylaia and axial planning in sanctuaries. Not copies, but shared choreography.

Column language. Early Egyptian rock-cut tombs at Beni Hasan show fluted, cushion-topped columns sometimes called “proto-Doric.” Many historians read them as cousins, not parents, of the Greek Doric. The safer takeaway is that fluting, entasis-like thickening and a love of clear rhythm were part of a Mediterranean conversation.

Myth vs Fact

Myth: The Greek Doric order was copied directly from Egypt.

Fact: Egypt had stone columns much earlier and some fluted forms appear in tombs, but Doric developed within Greek building culture. The relationship is influence and analogy, not one-to-one descent.

Ptolemaic Egypt fused Greek rule with Egyptian temple craft

After Alexander, Greek-speaking rulers governed Egypt but built like pharaohs in sacred architecture. That is why late temples such as Edfu and Dendera look “very Egyptian” in plan and program yet carry Hellenistic touches in carving and layout. The blend is visible in capitals, side chapels, roof stair reliefs and cosmic ceilings. At Philae the island plan turns the Nile itself into part of the ritual. Greek rulers used Egypt’s temple grammar because it still worked. The result became a model for how to inherit and adapt a sacred language without breaking it.

Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania (Kbor er-Roumia), 3rd–1st cent. BCE, Tipaza Province, Algeria.

Egypt in Rome: obelisks, Isis temples and city image

Rome makes the Egyptian echo loud. Emperors shipped obelisks to the capital and stood them in circuses and piazzas as monumental needles of state time. They were not ornaments only; they mapped power into the city plan and later became Baroque anchors. The cult of Isis arrived with an Egyptianizing temple language—pylons, cavetto cornices, sphinxes—translated into Roman construction. At Pompeii, the Temple of Isis shows a small, bright version of this blend: Egyptian forms scaled to a Campanian block.

Roman engineers also loved monolithic shafts for columns in baths and basilicas. Quarrying and hauling single pieces became a point of pride, a tradition Egypt had practiced for centuries. Even when forms changed—Roman arches and vaults do not come from Egypt—the aura of stone mastery traveled with every obelisk and granite column.

Case study: what Greeks and Romans learned from “sequence”

Pick one idea that ties this all together: sequence. Egyptian builders perfected the move from open to enclosed, from crowd to core. Greek sanctuaries absorb the lesson in their routes from gate to altar to cella. Roman urbanism scales it up: forums read as processional rooms under the sky, and triumphal processions behave like mobile temple liturgies. Once you see sequence as a design tool, it becomes easy to spot Egyptian DNA in later plans even when the details differ.

Roman amphitheatre of Kom El Dikka, Alexandria, 2nd–4th cent. CE.

Study it in order, then go see it

Start with the landscape and early capitals—Memphis on our map—then walk the classic temple grammar at Edfu and Dendera. Read cliff architecture at Hatshepsut and rock-cut theater at Abu Simbel. Close with the Giza machine—site plan, facts and inside story. That sequence gives you the Egyptian core. Only then compare with Greek gates and Roman city markers and the echoes will ring.

Conclusion: what truly traveled

Greece and Rome did not become Egyptian. They adopted moves: axial entries that declare a front, column forests that impress by rhythm, monoliths as symbols of state, and a love of procession as a design tool. Egypt’s lasting gift is not a single order or detail. It is the clarity of sequence, the courage to work stone at extreme scale and the instinct to let place—desert edge, river bend, cliff—write the first line of the plan. Learn those habits on the Nile and you will spot them across the Mediterranean.

Sources and Further Reading

UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology — “Mud-Brick Architecture” (2011)

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion — “Gods in Ancient Egypt” (2016)

Parco Archeologico di Pompei — “Tempio di Iside / Temple of Isis” (n.d.) (PDF)

UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology — “Portrait versus Ideal Image” (2010)

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion — “Ancient Egyptian Religion” (2018)