Archaic Greek Sculpture: Kouroi, Korai and the First Art Forms

These twin kouroi show how early Greek sculptors explored the human body with rigid poses, stylised faces and powerful legs.

Walk into a gallery of archaic Greek sculpture and it can feel a bit like entering a room full of people frozen mid-step. Tall stone youths stare past you, one foot forward, fists clenched. Young women stand perfectly upright, wrapped in elaborate drapery, their lips curved in a small fixed smile. At first glance everything looks stiff and repetitive. But if we line these statues up in time, something quietly amazing happens: the bodies begin to loosen, weight shifts, muscles round out, and the stone figures start to feel almost alive.

In this article we walk through that transformation. We will meet the kouroi (singular kouros, nude male youth) and korai (singular kore, draped maiden), see how they were used in sanctuaries and cemeteries, and follow their journey from blocky, formulaic shapes to statues that prepare the ground for the Classical miracles of Greek art. If you want to keep a broader context open while we zoom in, you can always cross-check with the wider map of ancient Greek art or our overview of ancient Greek sculpture as a whole.

Archaic Greek sculpture is the body of Greek statues and reliefs produced roughly between 700 and 480 BCE, before the Classical period, when artists first explored life-size stone and bronze figures.

What Do We Mean by Archaic Greek Sculpture?

Archaic Greek sculpture marks the moment when Greek artists commit to the human body on a new scale. Instead of decorating pots or carving tiny figurines, they suddenly start making free-standing statues as tall as, or taller than, real people. That choice changes everything.

Chronologically, the Archaic period sits between the abstract Geometric style and the better known Classical world. We are mainly in the sixth century BCE, give or take a few decades. In those years Greek workshops experiment with large blocks of marble and limestone, often inspired by contacts with Egypt and the Near East. You can feel this in the basic formula of a kouros: front-facing, left leg advanced, arms straight, fists clenched. The pose reads almost like a diagram for “human figure” rather than a portrait of a particular boy.

When we say “archaic sculpture”, we are not only talking about kouroi and korai. There are also architectural reliefs, small bronzes, terracotta figures, and grave markers. But the kouros and kore types are special because they are life-size, repeated again and again, and spread across the Greek world. They become the laboratory where Greek artists work out proportion, anatomy, and movement.

If you imagine this article as a mini-map, the kouroi and korai sit at the center. Everything else in archaic sculpture either leads towards them or grows out of them. Later Classical statues of gods and athletes, which we cover in our guide to ancient Greek sculpture, are almost unthinkable without this first century of trial and error in stone.

Teaching gallery of archaic sculpture casts, temple pediments and kouroi lining a bright corridor for close comparison.

Who Are These Kouroi?

A kouros is a standing statue of a nude male youth. Not a portrait in our modern sense, but a kind of formula for ideal young manhood. If you imagine a tall marble teenager with braided hair, arms straight, one leg stepping forward, you are already very close.

The earliest kouroi are almost strict patterns. Think of the so-called New York Kouros: the body is highly geometric, with sharp angles at the hips, knees and elbows. The chest is divided into neat, almost carved-in triangles. The eyes are large and almond-shaped. The whole figure feels rigid but confident, like a prototype fresh from the workshop.

Over the sixth century BCE that formula becomes more refined. The stone begins to behave more like flesh. A good way to see this change is to compare any early kouros with the more advanced Anavysos Kouros. In Anavysos the legs are thicker, the torso swells with subtle muscles, and the weight feels more believable. The pose is still frontal, but the figure no longer looks like a carved plank. He has volume, and he occupies space.

Functionally, kouroi served several roles. Many stood as grave markers for young aristocrats who died early. Others were set up in sanctuaries as costly offerings to the gods, especially Apollo. In both cases, the statue speaks about arete, the Greek idea of excellence. The eternal, perfect youth in stone stands in for the living person’s beauty, strength and status.

If you would like to go deeper into what makes a kouros a kouros, from hair patterns to inscriptions, we explore that step by step in our focused guide to the kouros statue.

Archaic kouros seen from the chest up, his archaic smile just beginning to soften a rigid, geometric treatment of the body.

And What About the Korai?

If the kouros embodies the ideal young man, the kore is his female counterpart. A kore is a standing maiden, usually slightly smaller in scale, always clothed, and often more intricate in surface detail. Where the kouros shows off muscle and bone, the kore shows off drapery, jewelry and color.

At first glance, korai may feel less dramatic because the body is hidden under layers of fabric. But if we look closely, they are incredibly rich objects. Take the famous Peplos Kore from the Athenian Acropolis. She wears a thick garment called a peplos, belted at the waist, with a mantle cast over her shoulders. Once upon a time this marble was painted in vivid reds, blues and greens. Traces of pigment on the surface and scientific tests show that korai were not white statues, but colorful presences that caught the light and the eye.

Korai usually stand with one foot slightly advanced, much like kouroi, but their arms are more active. One hand might hold an offering, like a pomegranate or a bird, while the other gathers up the fabric in a small gesture that both reveals and hides the body. That tug at the garment is a micro-drama: it suggests movement, modesty and grace all at once.

There is still debate about who these korai are. Some are probably idealized young women dedicated to a goddess, perhaps by their families. Others may actually be goddesses themselves, disguised in the same general type. When we ask whether a kore is a mortal maiden or a deity, we are already very close to the questions we tackle in our piece on how Greek god statues play with ideal bodies and divine identity.

A solitary kouros stands frontally, patterned hair and fixed pose balancing anatomical interest with frontal symmetry.

From Blocky to Almost Alive: How Style Changes Across the Sixth Century BCE

If we line up archaic statues in chronological order, the change in style is surprisingly readable with the naked eye. Early in the period, figures are flat and angular. By the end, they are rounder, more fluid, and clearly on the verge of Classical naturalism.

For kouroi, the story usually starts with very rigid examples. The shoulders are straight, the torso narrow, and the anatomy is drawn onto the surface like a diagram. These early works still feel close to Egyptian prototypes, where a strict grid controls the body. The Greek twist is that the statues are fully free-standing and completely nude, which invites a stronger focus on muscles and proportion.

As decades pass, sculptors take more risks. Kneecaps start to project, thighs bulge slightly, the transition from chest to abdomen softens. When we reach pieces like the Anavysos Kouros, the body carries its weight with more conviction. The spine curves a little, and the knees seem to lock and flex differently, even if both feet are still flat on the ground. The statue is beginning to anticipate movement, not just record a pose.

Korai undergo a similar journey, but through fabric instead of bare skin. Early korai are column-like, their garments indicated by shallow grooves. Later ones display cascading folds, diagonals that suggest a lifted heel, and delicate “wet drapery” effects that hint at the body underneath. The sculptor is learning how to use stone to show weight, gravity and softness all at once.

This evolution is why archaic sculpture matters so much historically. It is not only a style, but a process, a long drawing lesson in three dimensions. By the time Classical sculptors introduce full contrapposto, the relaxed pose where weight shifts onto one leg, a lot of the hard groundwork has already been done by these earlier, slightly awkward, yet incredibly ambitious statues.

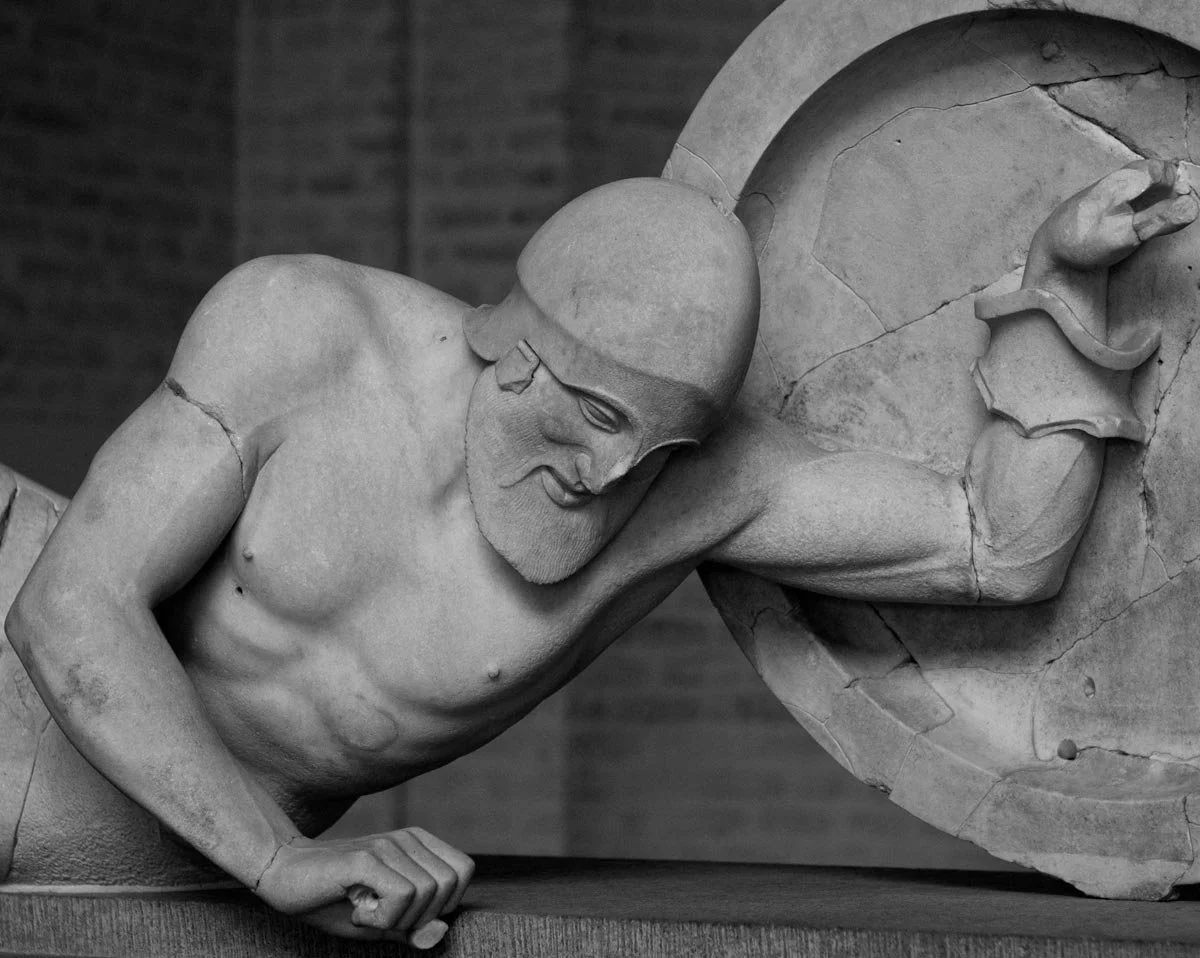

Dying warrior from the Temple of Aphaia pediment, body straining as he props himself on one arm and clings to his shield.

Why Are They All Smiling?

One detail that nearly everyone notices is the archaic smile. Kouroi and korai often have a fixed, gentle curve at the corners of the mouth. It can look charming, eerie or even a bit smug. What is going on there?

The first important point is that this is not a portrait smile caught at a specific emotional moment. The same mouth shape appears on warriors, maidens, mythic creatures and even grave markers for people who died violently. It is a convention more than a mood.

Many scholars think the smile signals that the figure is alive and blessed, in a state of well-being appropriate to a hero or a divine favorite. It visually separates the statue from a lifeless corpse and sets it closer to the gods. In this sense the archaic smile is a small sign of status, almost like a glowing halo in later Christian art.

From a practical point of view, the smile also helps the sculptor solve a technical problem. It lets the artist carve lower lips and cheeks in a way that catches the light and gives volume to the face. A straight neutral mouth carved in marble tends to look flat and dead. The curve creates shadow patterns that feel more dynamic.

If you want to dig deeper into interpretations, from early theories about “half-conscious grins” to recent readings that see the smile as a visual code for moral excellence, we unpack those debates in our dedicated article on the so-called archaic smile.

Where Did These Statues Stand, and What Did They Do?

It is easy to think of kouroi and korai purely as museum objects, but originally they lived in very specific settings. Understanding those settings changes the way we read them.

Many kouroi stood in sanctuaries, often lining processional routes or clustering around temples. In places like Delphi or the sanctuary of Poseidon at Sounion, visitors would walk past rows of standing youths, each dedicated by a particular family or city. The statue might carry an inscription on its base giving the name of the dedicator and sometimes a short boast about excellence in war or athletics. In this context, the kouros is both a gift to a god and a public advertisement for the donor’s prestige.

Other kouroi served as grave markers, set up along cemetery roads outside the city walls. The famous Kroisos kouros, for example, commemorated a young warrior who fell in battle, according to its base inscription. Here the statue functions almost like a perfected double of the dead person. The ideal, eternally youthful body stands where the mortal one lies buried, keeping memory present for passers-by.

Korai are especially associated with the Athenian Acropolis, where dozens were found buried after the Persian destruction of 480 BCE. Before that event they would have stood around older shrines and altars, glimmering with color and metal details. Some held offerings, others perhaps carried attributes that hinted at a specific goddess. In a sanctuary setting, these statues form a kind of stone crowd, each one a separate gift but also part of a shared visual environment of devotion.

Thinking about these original locations is useful when you look at a single statue in isolation. If you imagine it back in a busy sanctuary or along a road full of tomb markers, suddenly it is less abstract. It becomes a participant in rituals, festivals and family stories, not just an object behind glass.

Fragmentary kouros head with tight curls and faint smile, damaged marble that still conveys early Greek ideals of youth.

From Archaic Bodies to Classical Miracles

By around 480 BCE, Greek sculpture takes a decisive turn. Statues like the Kritios Boy, with their relaxed hips and subtle head turns, announce the start of the Classical period. But they do not come out of nowhere. They are heirs to a century of playful tweaking of the kouros and kore types.

You can feel the transition if you look at a late kouros alongside an early Classical youth. The basic structure is still there: standing, one leg slightly forward, weight distributed between both feet. Yet suddenly the hips tilt, the shoulders counter-tilt, and the head turns a fraction to one side. The body is no longer a fixed sign; it becomes a snapshot from a continuous movement.

The korai story merges into this shift as well. Their experiments with drapery, overlapping folds and hinted-at bodies underpin the spectacular “wet drapery” style of Classical goddesses. When you see the Parthenon’s carved maidens or later statues of Athena and Aphrodite, you are witnessing the afterlife of archaic fabric games.

This is why archaic Greek sculpture is such a good starting point if you aim to understand the full arc of Greek art. Learning to read kouroi and korai trains your eye to notice proportion, symmetry, surface and pose. It prepares you to appreciate both the radical leaps and the subtle continuities in later works, all the way to the Hellenistic period.

If you want to follow that arc forward, the next natural step is our broader overview of how ancient Greek sculpture evolves across periods and how it fits into the larger puzzle of ancient Greek art.

Conclusion

Archaic Greek sculpture can look repetitive at first. Rows of stone youths, rows of stone maidens, the same step forward, the same small smile. But once we slow down and walk through the sixth century BCE in sequence, the repetition turns into a story. We watch Greek sculptors teach themselves how to carve flesh out of marble, how to balance a rigid formula with individual presence, and how to make a statue do social work as grave marker, offering and symbol of excellence.

Kouroi and korai are more than “early versions” of later Classical masterpieces. They are experiments in what a human image can be, standing at the crossroads of religion, politics and aesthetics. When we read them carefully, we meet not only anonymous youths and maidens, but also the ambitions of families, the competition between city-states, and the slow discovery that stone bodies can carry complex ideas.

If you keep this in mind the next time you meet a kouros or a kore in a museum, try to imagine the statue back in its original crowd: along a dusty cemetery road at sunset, or catching the bright sun on the terrace of a sanctuary. In that imagined setting, the archaic smile starts to make sense. It is not simply a facial quirk, but a tiny sign that the figure has stepped into a different, more enduring kind of life.