Greek Pottery: How Everyday Vases Became Story on Surface

Rows of tiny lekythoi once held perfumed oil for graves and banquets, showing how painted pottery shaped intimate gestures and memories in Greek life.

Walk into any Greek gallery and you are surrounded by pots. At first they might blur into a sea of orange and black. Then you get closer and realise: these are not just containers, they are tiny cinemas. On the curve of a vase, someone is drawing a chariot race, a wedding, a funeral, a god arriving late to a party.

In this guide, we treat Greek pottery as both craft and storytelling. We move from clay and shapes to painting techniques and the favourite scenes that painters loved to repeat. You can read it on its own, or alongside our deep dives into Greek vases, black figure pottery and our wider map of ancient Greek art.

Definition

Greek pottery is the ceramic ware made in ancient Greece, used for storage and rituals and often painted with scenes from myth and daily life.

Greek pottery began as practical storage before it became art

The safest way into Greek pottery is to remember that, at the start, no one was thinking of museums. People needed containers that could store grain, pour wine, fetch water, mix drinks, offer oil to the dead. Pots were part of daily routines long before they were art history slides.

Greek potters worked with fine, iron rich clay that fired to a warm orange red. In Attica, the region around Athens, this clay became the base for the most famous wares. Workshops in the potter’s quarter shaped vessels on the wheel, added handles and mouths, then dried and fired them in kilns that required almost obsessive control of temperature and atmosphere. Technical studies show just how sophisticated that process was, especially for the painted wares.

Shapes followed function. The amphora is the all rounder: a two handled storage and transport jar that traders could stack in ships and people could reuse at home. We look at one specific version in our guide to the amphora vase. A krater is a wide bowl used to mix wine and water at symposia. Hydriai carry water from fountains, lekythoi hold perfumed oil, cups and kylikes sit in front of drinkers. Each shape has its own proportions and favourite scenes. If you want to go deeper into shapes specifically, you will find that in Greek vases.

Over time, some pots became special commissions. Fine figured vases were placed in graves, dedicated in sanctuaries or used as prizes at festivals. Others were exported in huge quantities, especially from Athens to places like Etruria. Archaeologists now rely on these pots not only to date excavation layers, but to reconstruct trade routes, tastes and even social habits. Greek pottery is, quite literally, the material that survives when most other things have disappeared.

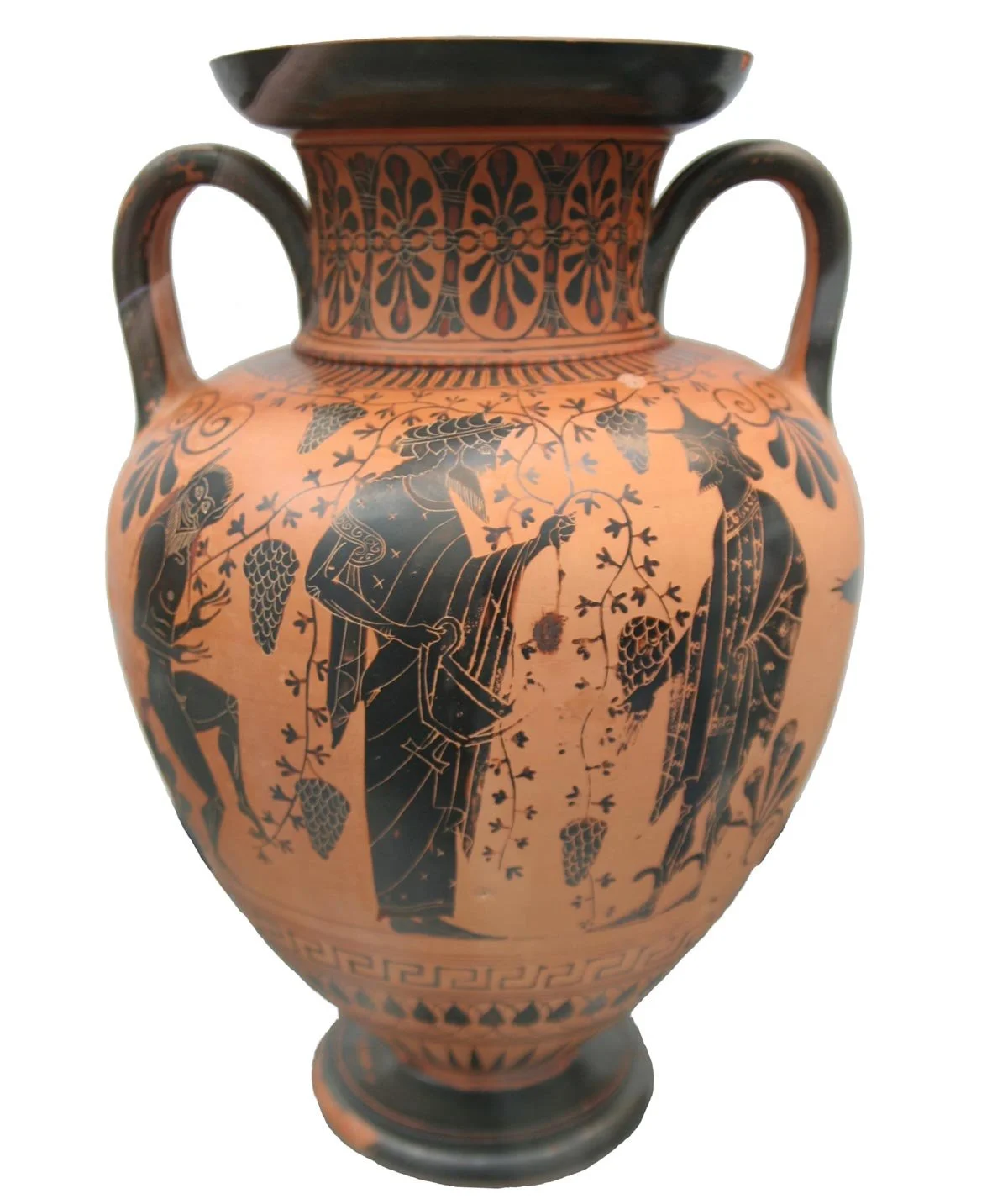

Black-figure amphora with Dionysos and his companions, where vines, wine and music turn a clay vessel into a tiny ritual stage.

Black figure and red figure turned vases into drawing surfaces

When we talk about Greek pottery styles, we are often really talking about painting techniques. The two big ones you will see everywhere are black figure and red figure. Understanding them turns the surface of a vase from “decoration” into something more like an artist’s sketchbook.

In black figure, painters covered figures with a glossy slip that fired black, leaving the background in the natural red of the clay. Details - muscles, folds of cloth, hair - were incised into that black layer with a sharp tool, so the red clay lines showed through. Extra colours like white or purple could be added for highlights. This technique dominates in the sixth century BCE and gives scenes a strong, graphic look.

Around 530 BCE, Athenian workshops flipped the logic and developed red figure. Now the background was painted black, while the figures were left in the red clay. Details were added with fine brushes using diluted slip, so you could draw interior lines instead of scratching them out. This allowed much subtler modelling of anatomy, poses and drapery. Within a few decades, red figure largely replaced black figure for high quality figure decoration. We break this transition down in more detail in our article on Greek black figure pottery.

White ground technique appears on some shapes, especially lekythoi used in funerary contexts. Here, a light slip creates a pale background, and figures are drawn in outline with added colour. The result feels almost like a drawing on paper, but it is more fragile, which is why these vases often have a specific, ritual use. Institutional guides and scholarly overviews all stress that these three techniques - black figure, red figure and white ground - mark major phases in Athenian ceramic production.

Once you see a vase as a controlled experiment in firing and painting, the craft behind each piece becomes clearer. That drinking cup with a tiny scene in the bottom is not just “cute”. It is the end point of a process that started with selecting clay and ended with precise kiln atmospheres.

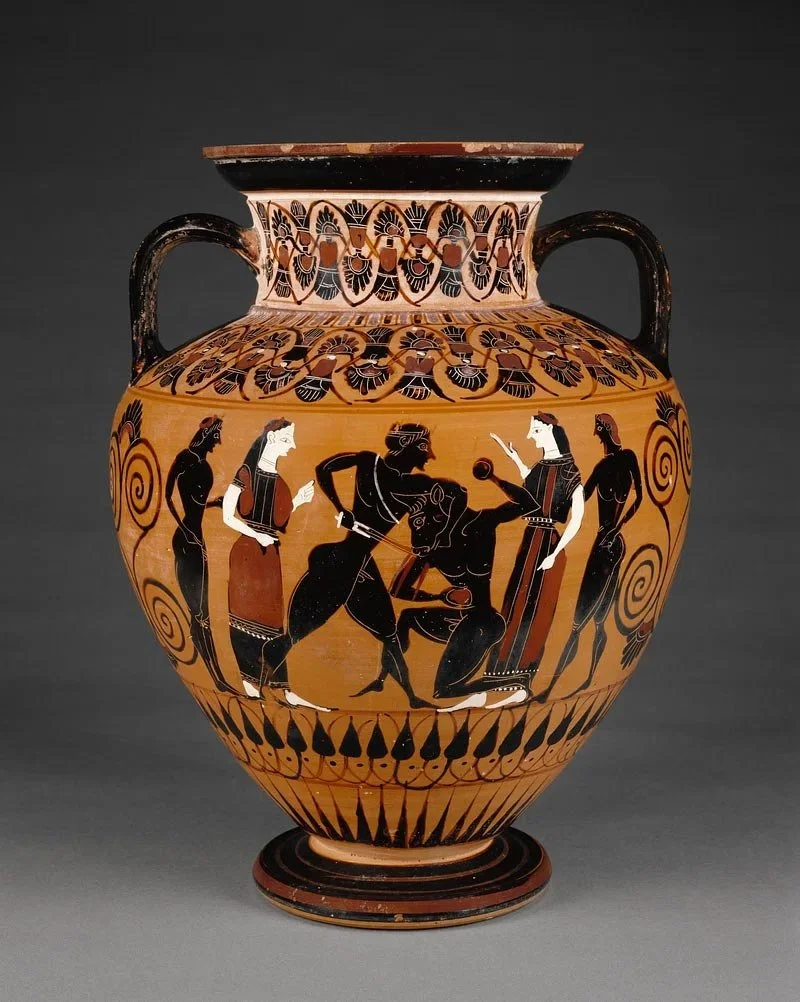

A narrative frieze of revelers circles this amphora, capturing the movement, music and excess at the heart of Dionysian worship.

Vases as stories: myths, daily life and patterns

If techniques turned pots into a kind of canvas, what did painters choose to show? The answer sits somewhere between gods and laundry.

A huge number of surviving vases carry mythological scenes. Heroes wrestling monsters, gods visiting banquets, episodes from the Trojan War: these all appear again and again. Painters seem to assume that viewers know the stories already, so they pick crucial moments or recognisable combinations of figures. Some modern books call vases “storytellers”, and museum essays emphasise that they are one of our richest sources for Greek myth outside texts.

Then there are the scenes of daily life. Athletes training in the palaestra, symposia with reclining drinkers, women at home preparing wool or managing funerary rituals - these moments are everywhere once you start looking. A famous essay from the Met notes that, as painters got more confident with complex poses, they expanded their repertoire of everyday activities, though often focused on the male citizen’s world. Vases quietly record how people moved, dressed, held tools, interacted with each other.

Do not ignore the patterns that frame these scenes. Meanders, wave bands, palmettes and other borders break up the surface into registers and focus areas. In our piece on Greek patterns, we treat these motifs as more than filler. They help guide your eye, anchor the figures to the shape, and sometimes echo the rhythm of architecture and textiles.

It can help to think of a painted vase as a collaboration. Potters decide the shape; painters choose scenes that suit that shape and function. A big storage amphora might carry a bold, frontal myth that can be recognised from a distance. A small perfume bottle might get a delicate, intimate scene. Looking at them with this in mind also links back to how we read larger images in ancient Greek paintings and Greek paintings more broadly, even though most wall painting has vanished.

Mini-FAQ

Q: What did Greek pottery usually show?

A: Greek pottery typically shows myths, athletic contests and scenes from daily life, framed by decorative patterns.

A refined red-figure vessel showing women at home, reminding us that Greek pottery also pictured quiet domestic rituals and care.

How to actually read a Greek vase today

In front of a display case, it is easy to feel overwhelmed. So here is a simple way to read a Greek vase without panicking.

First, walk around it if you can. Many narrative scenes unfold as you rotate the vessel, with one main side (the “A side”) and a secondary one. Notice which scene faces the main viewer and which sits on the back. That placement can tell you which story the painter or owner thought was most important.

Second, match shape to use. Ask yourself: storage, pouring, mixing, drinking, oil, water, ritual? Our article on Greek vases and the focused guide to the amphora vase can help you decode this. Knowing that a krater stood in the middle of a symposium or that a lekythos was placed by a grave changes how you read its pictures.

Third, scan the technique. Black figure, red figure or white ground will already put the vase in a rough time frame and tell you something about the painter’s toolbox. Pair that with what you know from broader ancient Greek art and you start placing the pot on your mental timeline.

Finally, look for patterns and gestures. Meanders might mark a boundary between myth and “real space”. The tilt of a head or the placement of a spear can signal emotion or movement in a very economical way. The more you compare different vases, the more you see recurring visual formulas that painters use to cue specific moments in a story. Scholarly work now mixes close visual analysis with scientific studies of clay and slip, and large digital databases like the Beazley Archive make it possible to trace similar scenes across hundreds of objects.

Once you have tried this a few times, even a quick visit to a museum case becomes less of a blur. Instead of “lots of pots”, you start to see a crowd of small voices, each telling its own version of Greek life and myth on a curved, fragile surface.

Conclusion

Greek pottery is one of those topics that can feel technical from a distance, all shape names and stylistic periods. But when we slow it down, a more human picture appears. We saw how pots began as hard working containers, then became finely tuned craft objects with specific shapes for specific tasks. We traced how black figure, red figure and white ground turned clay surfaces into places where painters could experiment with bodies, drapery and storytelling. And we watched myths, daily routines and patterns wrap themselves around these forms so that a storage jar could double as a narrative scroll.

For me, the most helpful shift is treating each vase as a meeting point between craft, image and use. When you connect what you have just read here with our focused guides to Greek vases, black figure pottery and broader ancient Greek art, you start to see that these objects are doing serious cultural work while still being everyday tools.

Next time you stand in front of a shelf of Greek vases, try reading just one carefully: shape, function, technique, scene, patterns. It is a small exercise, but it quietly trains the kind of looking that makes the whole ancient world feel closer and less abstract, one curve of clay at a time.