Theseus and Ariadne: How a Bronze Age Story Survives in Greek and Modern Art

Palagi’s canvas reimagines the myth at its quiet turning point, when Ariadne’s simple thread becomes a clever architectural tool for escaping the Labyrinth.

Picture this: a young hero walks into a dark maze to kill a monster. At the entrance, a princess presses something into his hand. Not a sword. A thread.

That simple gesture – Ariadne giving Theseus a thread – is one of the most powerful images in Greek myth. It is also a scene that artists never get tired of reimagining, from ancient vases to modern prints. In this guide we will follow Theseus and the labyrinth from Crete to Athens, then out into later Greek and modern art. We are not only retelling the story. We are asking how each age rewrites this Bronze Age love story to fit its own fears and hopes.

If you want the darker side of the monster and its maze, you can pair this with our article on the Minotaur and the labyrinth myth, where we focus on the creature and his underground prison. Here, we stay with the couple.

First, the myth: thread, maze and black sails

At its core, the Greek labyrinth myth is simple. King Minos of Crete forces Athens to send young men and women as tribute, to be thrown into a labyrinth at Knossos where the Minotaur lives. One year, the Athenian prince Theseus volunteers to go, planning to kill the monster and end the tribute. On Crete he meets Ariadne, Minos’ daughter. She falls in love with him and decides to help.

This is where the famous object appears: the thread. In some versions it is a ball of wool, in others a glowing crown or a special cord. Either way, Ariadne gives Theseus a way to mark his path in the maze so that he can find his way back after killing the Minotaur. He ties one end at the entrance, unrolls it through the twisting corridors, finds and kills the monster, then follows the thread back to the door. Together they flee Crete by ship.

On the way home, the story darkens. Theseus and Ariadne stop on the island of Naxos. There, the versions split. In one, Theseus abandons Ariadne while she sleeps. In another, the god Dionysus appears and claims her as his bride, forcing Theseus to leave her. In yet another, Artemis kills her on the island. Ancient authors disagree, and Greek vase painters hint at different endings.

The final twist is the black sails. Before leaving Athens, Theseus promised his father Aegeus that he would swap the ship’s black sails for white ones if he came back alive. He forgets. From a cliff near Athens, Aegeus sees the returning ship with black sails still raised, thinks his son is dead and jumps into the sea. Theseus arrives home victorious, but his first act as a hero comes wrapped in grief.

Already here we can see why the story never dies. It is not just a monster fight. It is a chain of charged scenes: a girl with a thread at a labyrinth door, a couple on a shore in the half-light, an old man watching a ship, a hero whose success costs him everything.

This red-figure krater captures the mythic couple Theseus and Ariadne in elegant line drawing, reminding us how Greek pottery doubled as both tableware and storytelling medium.

Ariadne’s role: helper, victim, bride, or all three?

If we look at the story through Ariadne’s eyes, the tone changes. She is not a side character. She is the pivot that makes the whole plot possible.

In most versions, Ariadne is a princess of Bronze Age Crete, a daughter of Minos and related to the world of Minoan civilization. She lives inside or near those sprawling Minoan palaces at Knossos that archaeologists link to the labyrinth idea, with their complex corridors, staircases and storage rooms. When Athenians arrive as victims, she falls for one of them and betrays her father to help him. That betrayal is emotional and political at the same time.

Ancient sources cannot agree on what Theseus needed in the labyrinth. Some say a simple ball of thread. Others mention a crown of light that helps him see in the dark. In the British Museum’s description of a seventh century BC chest, Ariadne is shown holding a special radiant crown, used to light the way for Theseus. Later vase painters often stick with the thread, since it is easy to show as a line connecting her hand to the hero. Either way, the message is the same: intelligence and care, not only strength, make the escape possible.

Ariadne’s fate on Naxos is even more fluid. Some versions emphasise betrayal by Theseus, others stress divine intervention by Dionysus, who rescues her from being left behind and turns her into his immortal wife. Greek authors debate whether she dies, marries, or is taken up to the stars. Modern readers often focus on the heartbreak: the woman who saves the hero is abandoned once she is no longer “needed.” Ancient religion pulls the story in another direction, turning her into a goddess linked to Dionysus and seasonal rituals.

So even before we look at art, we have a myth that can be read in very different ways. Ariadne can be a clever helper, a tragic victim of male ingratitude, a divine bride, or all of these at different stages. That flexibility is exactly what makes her such a rich subject for visual storytelling.

Mini-FAQ

What did Theseus use to escape the labyrinth?

Most versions say that Theseus used a thread or cord given by Ariadne to trace his path and find the exit again.

Did Theseus really abandon Ariadne?

Ancient sources agree that Ariadne is left on Naxos, but disagree on why, with some blaming Theseus and others saying Dionysus or the gods ordered it.

How Greek art shows Theseus and Ariadne

When we move to actual objects, Greek labyrinth mythology becomes visible in clay and paint. Greek vase painters do not just illustrate a “fixed” story. They pick moments and angles that matter to them.

A sixth century BC Etruscan hydria (water jar) in the British Museum shows Ariadne watching while Theseus fights the Minotaur. Above, Theseus and the bull-headed monster struggle. Below, a dance of women led by Ariadne and a lyre-playing Theseus fills the frieze. It is almost like two timelines in one image: violence in the upper band, celebration and future marriage in the lower one.

On a fifth century BC red figure kylix (drinking cup), also in London, we see a more intimate scene. Inside the cup, Theseus plays a small lyre while facing a woman identified as Ariadne, who lifts the hem of her dress and holds a flower. An inscription above greets the viewer. There is no monster, no maze, only a quiet moment of encounter between hero and princess, probably set before the descent into the labyrinth. If you compare that to the harsher scenes of Theseus stabbing the Minotaur on other vases, you can feel how artists enjoyed switching between action and tenderness.

Later, painters become fascinated by the abandonment on Naxos. One Apulian stamnos shows Theseus sneaking away while Ariadne sleeps, watched by gods who hint at her future with Dionysus. Here, the drama is psychological, not physical. Theseus is no longer the pure hero of the fight. He is a man slipping away, full of doubt or guilt. The fact that some vase painters specialise in exactly these bittersweet moments says a lot about how much ancient viewers enjoyed the emotional complexity of the myth.

Taken together, Greek art treats Theseus and the labyrinth as a sequence of visual “beats.” Sometimes the focus is on the technical problem of the maze, shown with winding patterns. Sometimes it is on the relationship between Theseus, Ariadne and Athena. Sometimes it is that single thin line of thread, drawn between two hands, carrying all the tension of risk and trust. For the architectural setting, you can read our guide to Minoan palaces, where we look at how the real palace at Knossos might have inspired the labyrinth image.

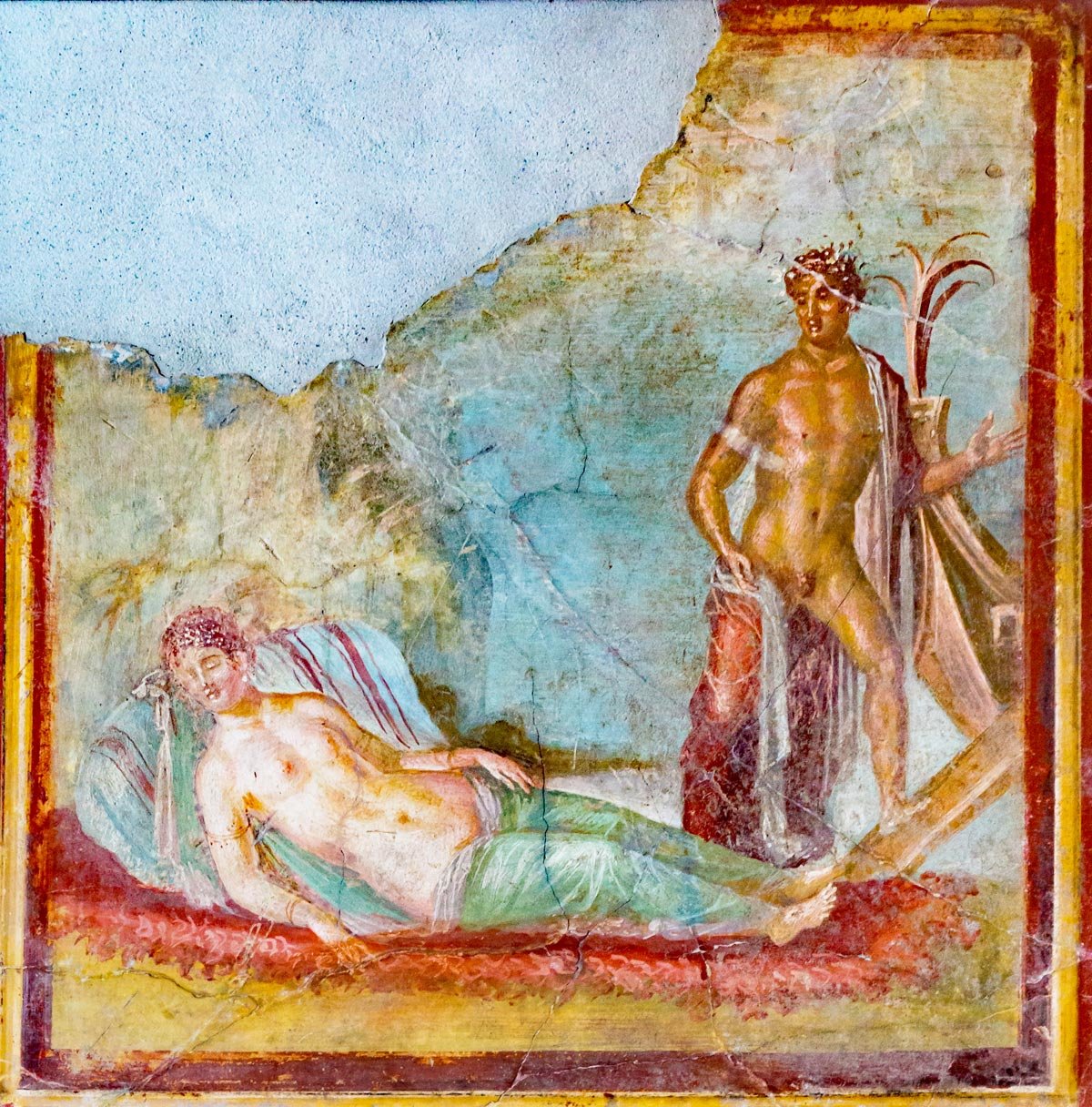

This Pompeian fresco retells the moment Theseus abandons Ariadne, showing how Greek myths were reimagined for Roman domestic interiors.

Modern retellings: from symbol of love to symbol of self

The story does not stop with ancient pots. Modern artists reuse Theseus, Ariadne and the Minotaur as a toolbox of symbols. Often, they shift the focus away from Athens and Crete and turn the labyrinth into a metaphor for the mind or society.

In the twentieth century, Pablo Picasso becomes obsessed with the Minotaur. In etchings like Minotaur with Dead Mare in front of a Cave, the man bull hybrid stands in for the artist himself, torn between violence and vulnerability. The labyrinth is no longer a literal building. It becomes the inner maze of desire, cruelty and creativity. Yet the basic triangle from the old myth remains: a dangerous male figure, a threatened or guiding female figure, and a space that traps them together.

Other modern works focus more directly on Ariadne and the thread. The thread becomes a symbol for narrative, memory or care. Writers and filmmakers retell the story from her perspective, asking what it means to save someone who later walks away. Some films and novels place a Theseus type in a modern city or institution that works like a labyrinth, then give him an “Ariadne” character who offers a map, a code, or an emotional lifeline. The basic pattern survives, even when the Minotaur has turned into trauma or oppression rather than a literal monster.

Museums also keep reinterpreting the story through exhibitions. The Ashmolean Museum’s recent projects on Knossos and the labyrinth explicitly invite visitors to think about how myths like this emerge from, and then reshape, real places such as Minoan civilization and its palaces. That loop between archaeology and storytelling is exactly where “Bronze Age story” turns into “timeless narrative.”

Conclusion

If we follow Theseus and Ariadne from Crete to Athens and then into later art, one thing becomes clear. The myth survives not because it gives us a single clear message, but because it is flexible and visual. A labyrinth, a thread, a sleeping girl on a shore, a ship’s sail seen from a cliff, a monster in the dark. These are images that artists can pick up and bend in many directions.

For the Bronze Age, the story probably reflects tensions between island powers like Crete and rising mainland centres, whose citadels we explore in our pieces on Minoan palaces and Minoan civilization. For classical Athens, Theseus becomes a civic hero who saves his city yet carries guilt. For modern creators, the labyrinth turns into psychology, the Minotaur into the darker self, and Ariadne into the person who offers a way through.

If this guide helps you see each image of Theseus, Ariadne and the labyrinth not as “illustration of a fixed story” but as part of an ongoing conversation, then you are already reading myth like an art historian. Next time you spot a thin line of thread in a painting, a maze in a film, or a bull headed figure in a drawing, you can ask yourself which version of the story is being told, and whose side it is on.