Why Egyptian Wall Paintings Still Dazzle Historians

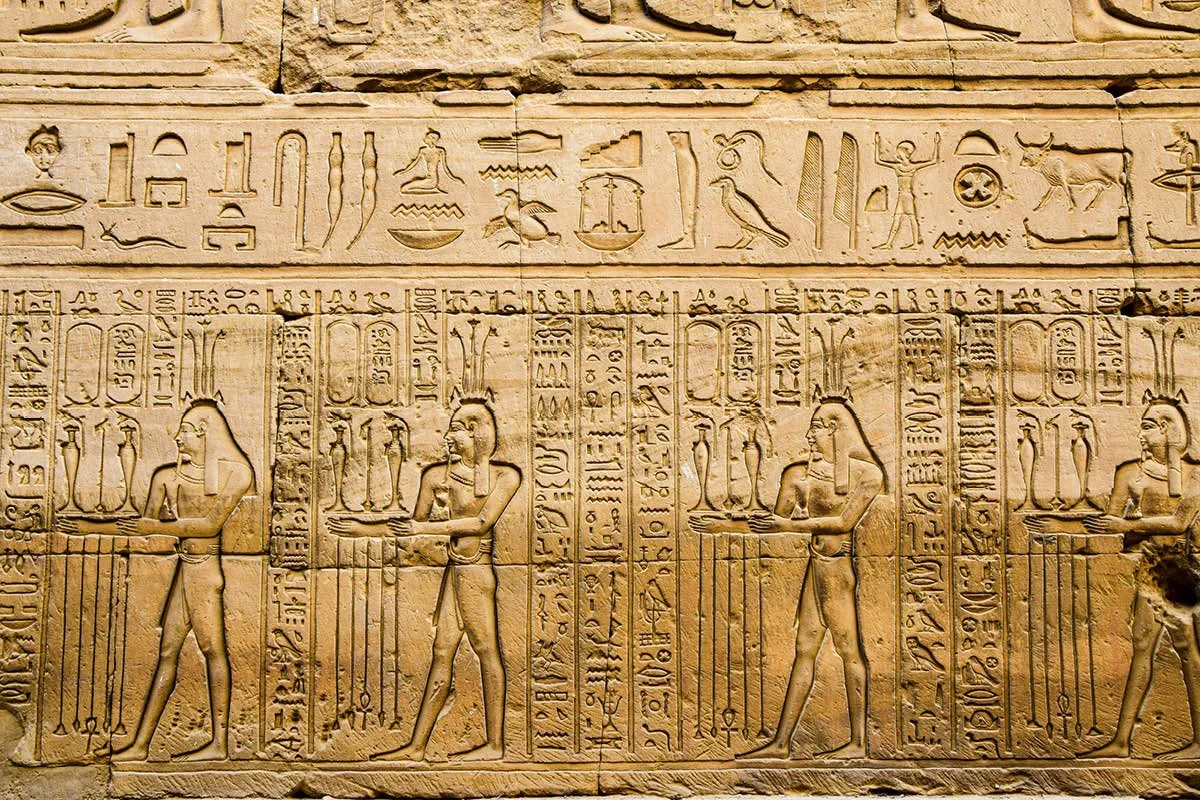

Offerings on the road to the afterlife.

Walk into a painted tomb and the color still works. Reds stay warm, blues stay cool, and thin black lines steady the whole scene. Egyptian wall paintings dazzle because they combine mineral color that ages well with a visual grammar that is easy to read. Once we learn the craft steps and the storytelling rules, the magic feels practical—then even more impressive. For the bigger picture of this language, keep our primer on ancient Egyptian art open while you read.

The simple trick: mineral color and clear rules

Egyptian color is built to last. Painters used mineral pigments—iron oxides for reds and yellows, carbon for black, gypsum for white, copper compounds for greens and blues—mixed with a water-soluble binder (gum or glue). The star is Egyptian blue, a man-made copper-calcium silicate that keeps its punch and even emits a soft near-infrared glow under certain light. This palette is not flashy chemistry; it is a dependable kit that stays stable in dry tomb air.

Clarity is the other half. Tomb rooms are narrow. Light is angled. So artists designed for fast legibility: large fields of flat color, contour lines that stay crisp, and figures planned on a grid so bodies look consistent from wall to wall. The familiar “composite view” (profile head and legs, frontal eye and torso) is a decision, not a mistake—it shows the most informative angle of each part. Scenes sit on ground lines and stack in registers so we can read them as we walk.

Definition

Register: a horizontal band that organizes a scene for easy reading.

There is variety, of course. Some periods prefer soft modeling; others sharpen outlines. In late temples, paint often rides on carved relief—check Dendera’s stair reliefs to see how incision and color cooperate. But across eras, the aim holds steady: make meaning visible in challenging spaces.

Processions painted in precise registers.

From wall to picture: how artisans built a scene

Most painting sequences follow a repeatable workflow. First, prepare the wall: smooth the stone, add a rough coat of mud or gypsum plaster, then a fine finishing coat. Next, snap grids with red lines to set proportions. Draftsmen sketch in red; master painters correct in black. Only then do teams lay flat colors, often light to dark, and finish with steady outline and small details for eyes, hands, and inscriptions.

Tools are simple and smart. Brushes are reed-fiber bundles cut to a point for line or splayed for fill. Bowed strings or cords help draw straight guidelines. Where carving and paint meet, carvers cut low relief so shadows are soft and outlines remain readable after painting. The result is a surface that performs at three distances: big blocks of color from across the room, figures and poses from a few steps back, and inscriptions you lean in to read.

Corrections are part of the craft. You’ll sometimes see pentimenti—ghost lines from earlier drafts—nesting under the final contour. At doorways and turns, figures pivot so we continue “toward” the main person, never away. Even damage tells the method: flaked high-points reveal undercoats; cleaned patches reveal the grid. Once you spot these layers, you can reconstruct the whole workshop rhythm wall by wall.

Stories with jobs: what tomb paintings were for

Tomb art was not decoration. It did work for the dead and for the living. Offerings painted on walls could “stand in” for real food and drink. Lists and captions named goods, titles, and family so the person remained identifiable forever. Scenes of farming, fishing, feasting, and music were not casual snapshots; they were renewable actions that the tomb owner could access in the next life. In short: pictures functioned as spells with pictures.

The casting is deliberate. The deceased appears healthy and recognizable. Servants, family, and estate workers support the story. Deities and symbols anchor the rules of judgment and rebirth. Texts and images talk to each other: captions label people and acts; figures show what the words say. That is why the grammar is conservative—when the stakes are eternal, you choose the reliable form.

Temple painting uses similar methods with different emphasis—more ritual scenes and state theology—but the reading tools are the same. If you want to see how tombs, objects, and belief fit together, jump to ancient Egyptian tombs for a friendly map of spaces and roles.

Ritual procession carved in low relief.

How to read one fast (on-site or in a museum)

Start with orientation. Find the doorway, then the main wall facing you. The most important figures usually sit near the visual center or at the end of a register sequence. Next, scan the registers left-to-right (or toward the main figure if the direction flips). Follow ground lines to stay anchored; look for scale shifts to spot rank.

Now, pair image and text. Read cartouches, labels, and offering lists that float near hands and tables. They are not captions added later—they are part of the mechanism. Finally, step back. These rooms were designed to be walked. If the scene gets clearer as you move, the painters nailed their brief.

Keep two anchors as you practice: the broader language in ancient Egyptian art and the spatial logic in ancient Egyptian tombs. Together they turn any painted wall into a readable page.

Conclusion: Built for clarity, built to last

Egyptian wall paintings still dazzle because they solve a tough problem—how to make belief readable in dim rooms for a very long time. Stable minerals, smart sequences, and a clear visual grammar kept the images working. Once you see the craft behind the glow, the glow doesn’t fade; it gets stronger.

Sources and Further Reading

The Metropolitan Museum of Art — “The Art of Ancient Egypt: A Resource for Educators” (1998) (PDF)

British Museum — “Notes for teachers: The paintings of the tomb of Nebamun” (2023) (PDF)

Smarthistory — “Materials and techniques in ancient Egyptian art” (n.d.)

Cambridge University Press — “Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology” (2000)