Who Were the Minoans? Crete, Palaces and the First Thalassocracy

The Hagia Triada sarcophagus records a complex ritual with music and sacrifice, giving us rare insight into how ceremony, sound, and movement worked together in Minoan religion.

Imagine arriving by boat on Bronze Age Crete. Ahead of you is not a single city wall, but a low, sprawling complex with bright red columns, open courtyards and painted walls. Storage rooms are filled with jars of oil and grain. Somewhere inside, officials count offerings with clay tablets while, outside, people gather for a festival in the sun.

This is the world we call Minoan civilization. It flourished on Crete long before classical Greece, shaped by palaces, sea routes and a vivid visual culture. Later Greeks wrapped it in myths about King Minos, the Labyrinth and the Minotaur. Archaeology gives us a quieter but richer picture: farmers, sailors, artisans and officials building a complex island society.

In this explainer we will meet the Minoans in four steps: who they were, how their palaces worked, what their art and religion looked like, and how their legacy survives in myth and later Greek culture. If you want to go deeper into specific buildings and images, you can pair this with our guides to Minoan palaces and Minoan frescoes, where we zoom in on architecture and wall painting.

The Minoans were a Bronze Age island civilization centered on Crete

When we say Minoan civilization, we are talking about a Bronze Age culture that developed on the island of Crete, roughly between 3000 and 1450 BCE. The name “Minoan” is modern. It was coined in the early 1900s by archaeologist Arthur Evans, who connected the remains at Knossos with the legendary King Minos. The people themselves did not leave us a clear self-name in a readable script.

Crete is a long, mountainous island with fertile plains, high plateaus and many small harbours. Its position in the eastern Mediterranean makes it a natural meeting point between Egypt, the Near East and the Aegean. That geography matters. From early on, Cretan communities farmed grain, olives and grapes, raised sheep and goats, and sailed to trade textiles, pottery and surplus goods. Contacts with Egypt and the Levant bring in ideas, objects and perhaps people.

Minoan history is usually broken into phases: Early, Middle and Late Minoan, each with sub-phases. For our purposes, the key moment is around 1900 BCE. At that point, large palatial centres appear at places like Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and later Zakros. These complexes become hubs for administration, storage, ritual and craft. They mark the start of what we could fairly call a Cretan thalassocracy, a sea-focused power that uses ships to project influence across the Aegean.

We know the Minoans wrote in at least two scripts, including Linear A, which is still undeciphered, and a set of hieroglyphic signs. Later, an adapted script called Linear B appears on Crete under Mycenaean control. If you want to follow that writing story in detail, we explore it in our explainer on Linear A and Linear B. For now, the important point is that Minoan administration was literate, but most of its texts are still locked to us.

Definition: Minoan civilization is the Bronze Age culture of Crete, active c. 3000–1450 BCE, known for its palaces, sea trade, vivid art and complex rituals.

Minoan palaces turned Crete into a seaborne power

If you want to feel Minoan society in one building type, you go to the palace. These are not palaces in the simple “king’s house” sense. They are multi-function complexes with storage magazines, shrines, workshops, administrative rooms and large open courts. Knossos is the most famous, but Phaistos, Malia and Zakros matter just as much for understanding how the system worked.

Architecturally, most palaces share a basic pattern. A central court sits at the heart, rectangular and open to the sky. Around it, multi-storey wings hold rooms for storage, ritual and residence. Corridors can be surprisingly indirect, turning corners and creating layered views. Certain room types repeat across sites: lustral basins sunk into the floor, pillar crypts, light wells and long rows of storage rooms filled with huge pithoi jars. Even when we debate the details, it is clear that these buildings organised movement and attention very carefully.

One striking feature is the lack of massive defensive walls in the earliest palatial phases. Instead of fortifying their centres like mainland Mycenaean citadels, Minoan palaces rely on position, planning and perhaps diplomacy. Their strength lies in control of resources and networks rather than brute stone bulk. Warehouses of oil and grain, workshops for textiles and metal, and controlled access routes make the palace a machine for concentrating goods and people.

From these nodes, Crete projects power over the sea. Minoan pottery and objects appear across the Aegean and in Egypt and the Levant. Egyptian paintings show ships that look very similar to Aegean vessels. Some scholars argue for direct Minoan rule over other islands. Others see more of a trading and cultural sphere than a formal empire. In either case, it is fair to call the Minoan world a thalassocracy, a sea-based system where ships are as important as walls.

Myth vs Fact

Myth: The Minoans were a single peaceful kingdom ruled forever by King Minos.

Fact: Minoan Crete was a complex island society with multiple palatial centres, shifting power and both peaceful trade and episodes of destruction.

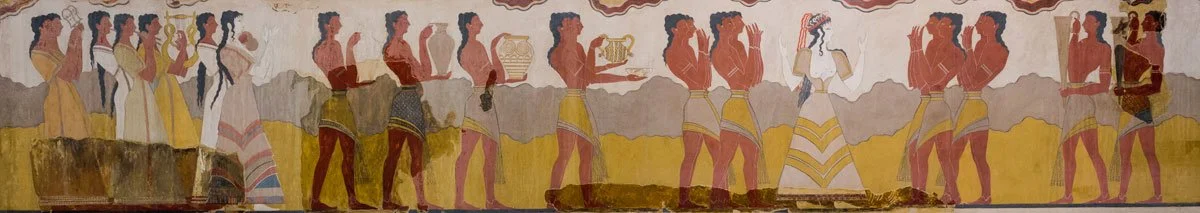

This long procession fresco suggests that moving through palace corridors was itself a ritual act, turning architecture into a stage for communal display.

Minoan civilization art: frescoes, objects and everyday beauty

If Cycladic art is about small marble bodies, Minoan civilization art is about painted surfaces and moving scenes. Palace walls at Knossos, Phaistos and other sites carry frescoes of bull leapers, processions, dancers, plant-filled landscapes and sea life. Figures are slim, with narrow waists and flowing hair. Colours are strong and flat. There is a sense of motion even in ritual scenes.

These wall paintings are not decoration in the modern sense. They mark certain spaces as special, guide visitors, and probably replay important stories or rituals. A corridor lined with images of people bringing offerings feels very different from a plain stone passage. In our visual guide to Minoan frescoes we look closely at particular scenes like bull-leaping and the famous “Parisienne” figure to see how style and meaning work together.

Beyond walls, Minoan artists work in many media. Potters create Kamares ware with thin walls and energetic patterns, then later marine-style vases wrapped in octopus arms and seaweed. Seal engravers carve tiny scenes on stones that are used to stamp clay sealings, combining practical control with miniature art. Metalworkers produce jewellery, ceremonial daggers and vessels in bronze and precious metals. Even basic objects often show a taste for curved lines and natural motifs.

What stands out is how integrated art is in daily and ritual life. Storage jars can be plain, but elite sets show careful design. Floors and thresholds use contrasting stones. Small shrines have figurines and offerings that blend craft and worship. Minoan culture does not keep art in a separate category. It builds imagery into architecture, containers and tools. That saturation is part of why the civilization still feels so visually alive to us.

Minoan religion and ritual: what we can say without over-inventing

Talking about Minoan civilization religion is where we need to be careful. We have lots of images and contexts, but no surviving sacred texts and only a handful of readable inscriptions from later periods. That means we are working with models rather than certainties.

Certain patterns repeat. Many Minoan images show women in prominent positions: standing on mountain peaks, holding snakes, or flanked by animals. Shrines and seal stones often combine female figures with symbols like double axes, horns of consecration, trees or pillars. This has led some scholars to talk about a “Great Goddess” at the centre of Minoan belief. Others prefer to see a cluster of related female and male powers linked to fertility, mountains, animals and the sea.

Ritual spaces come in several types. Inside palaces we find sanctuaries, pillar rooms and bench shrines. Outside, there are peak sanctuaries on high hills and sacred caves, both filled with votive offerings such as clay figurines and small models. These places suggest a religion that connects built centres with dramatic natural locations. Festivals in palace courts, processions to peaks, and quieter cave rituals likely coexisted and overlapped.

We also see signs of sacrifice and feasting. Animal bones in certain contexts, along with cooking and serving wares, point to communal meals that may have had religious meaning. Libation tables and offering stands suggest liquid offerings, perhaps of wine, oil or milk. The famous bull imagery, from horn symbols to bull-leaping scenes, hints at powerful rituals involving animals and possibly displays of elite prowess.

What we do not have is a simple, unified “Minoan religion” with a clear pantheon and dogma. Instead we see patterns of practice: mountains and caves, female figures and animals, processions and offerings, woven into everyday and political life. In our dedicated article on Minoan religion we unpack these strands one by one, but even there the emphasis is on careful inference rather than grand claims.

The Campstool fresco highlights the elegance of elite Minoan women, from their patterned textiles to the refined objects that structure their social rituals.

Myths and afterlives: Minos, the Labyrinth and later Greece

The Minoans do not vanish when their palaces burn. Around 1450 BCE, many Cretan centres suffer destruction. Mycenaean Greeks from the mainland likely take over Knossos for a time, using Linear B to record offerings and goods. Eventually even Knossos falls. But the memory of Minoan Crete lives on in later Greek myth.

Classical writers speak of King Minos, son of Zeus and Europa, and of a vast Labyrinth built by Daedalus to house the Minotaur. They tell stories of Theseus sailing from Athens to Crete to kill the monster and escape with the help of Ariadne and her thread. They describe Minos as a great sea king, the first to rule the waves and enforce order in the Aegean.

Archaeology does not confirm the myths in a literal sense. There is no single “Labyrinth building”, no skeleton of a Minotaur. What it does give us is something subtler: huge, multi-level palaces with complex corridors, storage rooms and staircases. To someone from a simpler mainland town, walking through Knossos could easily feel like entering a maze ruled by a powerful figure. The idea of a first thalassocracy, a seaborne power based on Crete, also fits what we know about Minoan trade and influence.

Later Greek art and ritual continue to echo some Minoan themes. Bulls remain significant in myth and sacrifice. Certain dance and athletic traditions may preserve distant memories of court performances. At the same time, classical Greeks also project their own concerns back onto Crete, turning Minoan stories into moral tales about hubris, justice or cleverness.

For us, the trick is to enjoy the myths while keeping them separate from the archaeological record. Minoan civilization is interesting enough on its own terms. The legends of Minos and the Labyrinth are one of its afterlives, not its only reason for mattering.

Conclusion

Minoan civilization is one of those topics that rewards every extra layer of attention. At first you see only bright frescoes and famous ruins. Then you start to notice the quieter things: the storage rooms, the workyards, the peak sanctuaries, the way a staircase frames a patch of sky. Behind the myths of Minos and his navy, there is a long-lived island society learning to use architecture, art and the sea to hold itself together.

For our journey through art history, the Minoans sit at an interesting crossroads. They borrow and adapt ideas from Egypt and the Near East. They share the Aegean with Cycladic islanders and mainland communities who will later become the Mycenaeans. They show how a relatively small landmass can become a cultural amplifier when it learns to work with ships, surplus and spectacle.

If this guide leaves you with a clearer sense of who the Minoans were, and also with a few open questions you want to chase through palaces, frescoes and scripts, then it has done its job. The next steps might be to walk through a plan of Knossos, follow a single bull-leaping fresco in detail, or track how Minoan and Mycenaean worlds collide. The sea in the middle of it all is still there, waiting.

Sources and Further Reading

The Metropolitan Museum of Art — “Minoan Crete” (2002) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Smarthistory — “Minoan art, an introduction” (2020) (Smarthistory)

Khan Academy — “Minoan art, an introduction” (n.d.) (Khan Academy)

Open Textbook Library — Ezra — “Guide to Ancient Aegean Art” (2020) (Open Education)

Watrous — Minoan Crete: An Introduction (excerpt, 2021) (Cambridge Assets)

Preziosi — Aegean Art and Architecture (Oxford University Press, 1999) (Internet Archive)

Panagiotopoulos, ed. — Minoan Realities (Presses universitaires de Louvain, 2012, open access) (books.openedition.org)