Why Did Egyptians Build a Pyramid Inside a Pyramid?

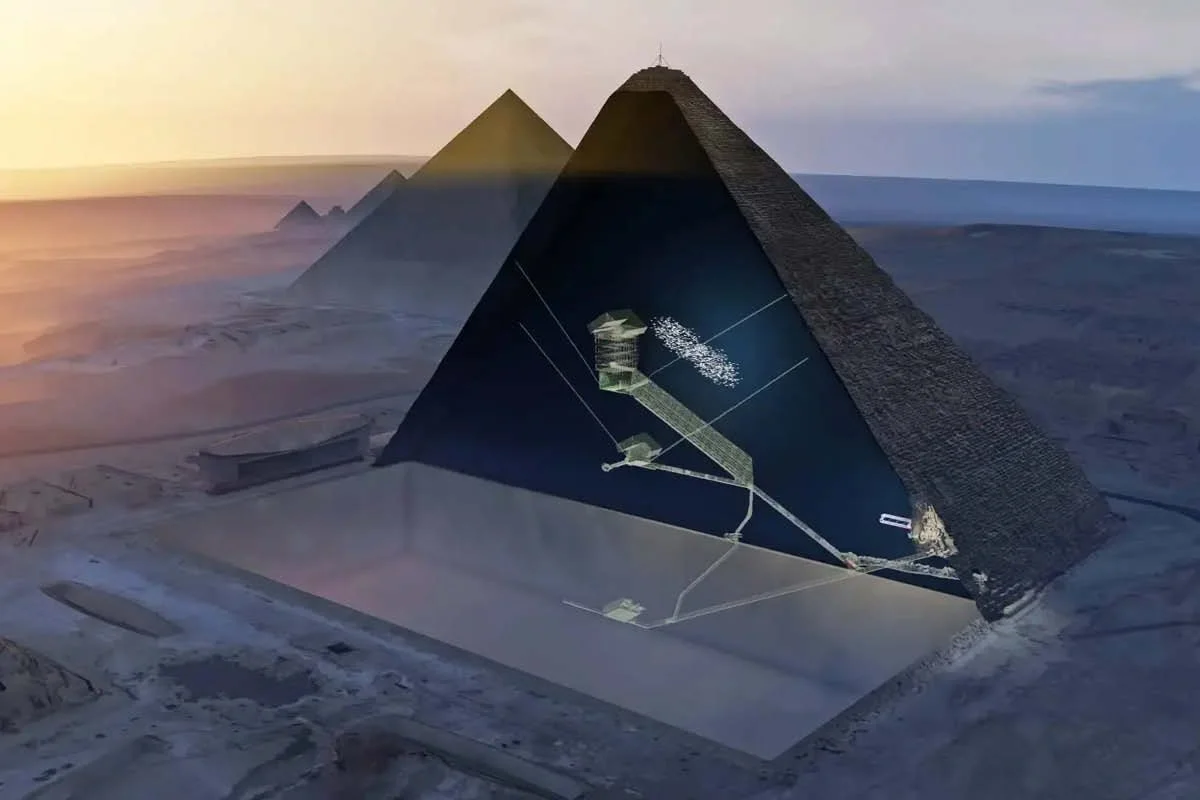

Great Pyramid interior [Cutaway render].

Short answer: they didn’t. What looks like “a pyramid within a pyramid” is a stack of nested solutions that let the monument breathe, carry weight, and stage ritual. Inside the mass you find corridors, chambers, and relieving spaces that redirect pressure away from a royal room. Once we see the interior as engineering that protects ceremony, the shape reads as a smart machine, not a mystery. For the wider design logic that repeats across the Nile valley, keep ancient Egyptian architecture in view.

The claim: no mini pyramid inside, just rooms and stress control

The Great Pyramid’s interior is a network of passages and rooms with structural cushions above them. The King’s Chamber sits like a granite box in the core. Over its flat ceiling, builders stacked five small cavities and capping blocks to deflect load to the sides. Those cavities are not symbolic rooms. They are relieving chambers that break the vertical pressure path. Nearby, the Grand Gallery rises with corbelled walls. Its stepped profile stiffens the corridor and likely doubled as a controlled staging ramp while heavy elements moved upward. The effect is layered because it has to be. A stone mountain needs routes, voids, and baffles so its important space does not crush itself.

Myth vs Fact

Myth: There is a smaller pyramid hidden inside the Great Pyramid.

Fact: The interior is chambers, passages, and stress-relief voids built for structure and ritual.

The layers you can actually prove

Another reason the “inside a pyramid” idea sticks is phased construction. Some pyramids grew in envelopes. At Meidum, a stepped core was expanded and cased into smoother faces, leaving a literal inner form inside the final mass. The Bent Pyramid records a mid-build change of slope, so two angle systems coexist. Even at Giza, you can think in layers without invoking a nested pyramid. Crews laid courses, thickened cores around passages, then wrapped the monument in a fine Tura limestone casing that closed and brightened the geometry. If you peel back that skin in your mind, you see practical inner masonry, not a finished second pyramid.

The same layered thinking extends beyond a single monument. A Pyramids of Giza site plan shows quarries, harbor traces, causeways, worker housing, and cemeteries operating together. The “layers” are not only inside one pyramid. They are in the system that fed it.

Khufu’s pyramid plan [Diagram].

Why those voids keep making headlines

Recent muon imaging mapped a large void above the Grand Gallery and other cavities in the core. These results are exciting, but they are still voids, not a second building. They likely mark stress relief, construction corridors, or spaces left by an internal transport route that was sealed once its job ended. In Egyptian stonework, leaving empty space can be as structural as placing a block. Emptiness deflects force, creates workroom during the build, or keeps a smooth exterior from telegraphing cracks. Calling these discoveries “a pyramid inside” misses the point. The point is intentional empty space used as a tool.

If you want the practical side of moving stone to the right place at the right time, our Great Pyramid facts explainer walks through quarrying, sledges on wetted tracks, ramps, and seasonal labor. The interior choices then feel inevitable rather than mysterious.

The purpose that anchors the plan

Everything inside serves a ritual center. Passages shape an approach, chambers hold equipment and symbolic roles, and the protected room hosts the king’s body or cult focus. Structure and ceremony are not separate topics. They are a pair. The chamber must be readable, dry, and intact for a very long time. The surrounding mass must carry sun, wind, and time without shifting. This is why the inside looks layered and why the outside once flashed with polished casing. The machine was tuned from core to skin.

Materials and geometry: why limestone plus granite works

The “layers” aren’t decorative; they reflect material jobs. Most of the mass is local limestone, good in compression and quick to quarry in big volumes. The casing was fine Tura limestone that locked the outer geometry and shed rain with tight joints. Inside the core, builders reserved Aswan granite for high-stress zones: portcullis blocks and the roof of the King’s Chamber. Granite is stiff and strong, but flat granite beams under millions of tons will still want to crack if weight bears straight down. That is why the chamber sits under stacked relieving spaces and—at the top—paired sloping blocks that act like a stone gable to push load sideways into the limestone mantle. Elsewhere, corbelling spreads forces by stepping courses inward (the Grand Gallery is the clearest example). Add survey accuracy and a stable square base, and you get a core that can carry itself for millennia. None of this requires exotic tech; it’s materials matched to tasks at scale. If you want to place these choices in Egypt’s broader building playbook, zoom out with ancient Egyptian architecture and then back in with our Great Pyramid facts for tools and logistics.

Khufu’s blocks up close: scale in stone.

Mini-FAQ: the two questions everyone asks

Is there a secret second pyramid inside?

No. Inside you have rooms, passages, and deliberate voids (relieving spaces and construction corridors). Recent scans revealed a large void above the Grand Gallery, but that’s a structural or build-phase space, not a hidden monument. For site context, the Pyramids of Giza site plan shows how quarries, causeways, and cores fit together.

Did they use an internal ramp the whole way up?

Possibly in sections, alongside external ramps and short lifting stages. Egyptologists accept multiple ramp forms across projects; no single ramp explains every phase. What matters for the “pyramid inside” idea is that temporary routes could leave sealed cavities behind—useful voids, not a second pyramid. For the practical build rhythm—sledges on wetted tracks, levers, survey—see Great Pyramid facts.

Conclusion: layered thinking, not a hidden building

Egyptians did not hide a little pyramid inside a big one. They stacked solutions: chambers to stage belief, voids to manage weight, and envelopes to finish the form. The surprise is not a secret structure. It is how ordinary methods scale into extraordinary precision. To place this inside story in its landscape, open our Pyramids of Giza site plan and scan back across ancient Egyptian architecture. The headline becomes cleaner: not mystery, but mastery.

Sources and Further Reading

Harvard University — “Digital Giza: Royal Pyramid Complexes” (n.d.)

Ancient Egypt Research Associates — “The Lost City of the Pyramid Builders” (n.d.)

Dash, G. — “Occam’s Egyptian razor: the equinox and the alignment of the pyramids” (2017) (PDF)

Bonn, D. et al. — “Sliding Friction on Wet and Dry Sand” (2014)

You may also like

-

January 2026

6

- Jan 6, 2026 Greek Patterns: Meanders, Waves and Palmettes in a Nutshell Jan 6, 2026

- Jan 5, 2026 What Is the Archaic Smile? Why Greek Statues Seem to Grin Jan 5, 2026

- Jan 4, 2026 What Is a Kouros Statue? Quick Guide to Archaic Greek Youths Jan 4, 2026

- Jan 3, 2026 What Is an Amphora Vase? A Quick Guide to This Greek Icon Jan 3, 2026

- Jan 2, 2026 Doric Column: The Simplest Greek Order in Plain Language Jan 2, 2026

- Jan 1, 2026 Athena Symbols in Art: Owls, Olive Trees and the Aegis Jan 1, 2026

-

December 2025

34

- Dec 31, 2025 Greek God Statues: How the Gods Looked in Ancient Greek Art Dec 31, 2025

- Dec 30, 2025 Ancient Greek Religion: Temples, Sacrifices and Belief Dec 30, 2025

- Dec 29, 2025 Peplos Kore: Color and Identity on the Athenian Acropolis Dec 29, 2025

- Dec 28, 2025 Anavysos Kouros: A Fallen Warrior Between Life and Stone Dec 28, 2025

- Dec 27, 2025 Greek Key Pattern: Why the Meander Border Is Everywhere Dec 27, 2025

- Dec 26, 2025 Greek Paintings: Frescoes, Panels and Fragments Explained Dec 26, 2025

- Dec 25, 2025 Ancient Greek Paintings: The Few Images That Survived Dec 25, 2025

- Dec 24, 2025 Greek Black-Figure Pottery: How Greeks Painted in Silhouette Dec 24, 2025

- Dec 23, 2025 Greek Vases: Shapes, Names and How the Greeks Used Them Dec 23, 2025

- Dec 22, 2025 Greek Pottery: How Everyday Vases Became Story on Surface Dec 22, 2025

- Dec 21, 2025 Ionic Columns: How They Differ from Doric and Corinthian Dec 21, 2025

- Dec 20, 2025 Types of Columns: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian for Beginners Dec 20, 2025

- Dec 19, 2025 Ancient Greek Fashion: What People Actually Wore Every Day Dec 19, 2025

- Dec 18, 2025 Ancient Greek Houses: How People Lived Behind the Temples Dec 18, 2025

- Dec 17, 2025 Ancient Greek Map: Main Ancient Cities and Sanctuaries Dec 17, 2025

- Dec 16, 2025 Ancient Greek City-States: How the Polis Shaped Art Dec 16, 2025

- Dec 15, 2025 Ancient Greek Structures: Temples, Theatres and City Walls Dec 15, 2025

- Dec 14, 2025 Greek Architecture: Columns, Temples and Theatres Explained Dec 14, 2025

- Dec 13, 2025 Ancient Greek Sculpture: From Archaic Smiles to Classical Calm Dec 13, 2025

- Dec 12, 2025 Ancient Greek Art: A Guide from Geometric to Hellenistic Style Dec 12, 2025

- Dec 11, 2025 Archaic Period in Greek Art: Geometric Schemes and Full Figures Dec 11, 2025

- Dec 10, 2025 Geometric Art in Greece: Lines, Patterns and Tiny Horses Dec 10, 2025

- Dec 9, 2025 Greek Temples: How the Ancient Greeks Built for Their Gods Dec 9, 2025

- Dec 8, 2025 Archaic Greek Sculpture: Kouroi, Korai and the First Art Forms Dec 8, 2025

- Dec 7, 2025 Linear A and Linear B: The Scripts of the Aegean Dec 7, 2025

- Dec 6, 2025 Cyclopean Masonry in Two Minutes Dec 6, 2025

- Dec 5, 2025 What Is a Megaron? Dec 5, 2025

- Dec 5, 2025 Theseus and Ariadne: How a Bronze Age Story Survives in Greek and Modern Art Dec 5, 2025

- Dec 4, 2025 From Minoans to Mycenaeans: What Changes in Art and Power? Dec 4, 2025

- Dec 3, 2025 The Lion Gate at Mycenae: Architecture, Symbol and Power Dec 3, 2025

- Dec 3, 2025 Mycenaean Architecture: Megaron, Citadel and Cyclopean Walls Dec 3, 2025

- Dec 2, 2025 Who Were the Mycenaeans? Fortress-Cities and Warrior Kings Dec 2, 2025

- Dec 1, 2025 Minoan Wall Paintings: Bulls, Dancers and Island Landscapes Dec 1, 2025

- Dec 1, 2025 Religion in Minoan Crete: Goddesses, Horns and Sacred Peaks Dec 1, 2025

-

November 2025

36

- Nov 30, 2025 The Labyrinth and the Minotaur: From Knossos to Later Greek Art Nov 30, 2025

- Nov 30, 2025 Bull-Leaping Fresco: Sport, Ritual or Propaganda? Nov 30, 2025

- Nov 30, 2025 How Minoan Palaces Worked: Knossos, Phaistos and the “Labyrinth” Idea Nov 30, 2025

- Nov 30, 2025 Who Were the Minoans? Crete, Palaces and the First Thalassocracy Nov 30, 2025

- Nov 29, 2025 Daily Life in the Cyclades: Homes, Graves and Sea Routes Nov 29, 2025

- Nov 28, 2025 The Plank Idols: How to Read a Cycladic Figure Nov 28, 2025

- Nov 27, 2025 Why Are Cycladic Idols So “Modern”? Minimalism Before Modern Art Nov 27, 2025

- Nov 26, 2025 What Is Cycladic Art? Marble Idols, Graves and Meaning Nov 26, 2025

- Nov 25, 2025 Bronze Age Ancient Greece: From Cycladic to Mycenaean Art Nov 25, 2025

- Nov 24, 2025 Aegean Art Before Greece: Cycladic, Crete and Mycenae Explained Nov 24, 2025

- Nov 16, 2025 Eye of Ra vs Eye of Horus: 5 Key Differences Nov 16, 2025

- Nov 15, 2025 Mummification Meaning: purpose, symbols, tools Nov 15, 2025

- Nov 14, 2025 Memphis: Site Dossier and Early Capital Nov 14, 2025

- Nov 14, 2025 The First Dynasty of Egypt: a Complete Framework Nov 14, 2025

- Nov 13, 2025 How Ancient Egyptian Architecture Influenced Greece and Rome Nov 13, 2025

- Nov 12, 2025 7 Facts That Make Tutankhamun’s Mask a Masterpiece Nov 12, 2025

- Nov 12, 2025 A Visual Framework for Studying Egyptian Sculptures Nov 12, 2025

- Nov 11, 2025 Inside the Pyramids of Giza: chambers explained Nov 11, 2025

- Nov 10, 2025 Philae Temple: Isis Sanctuary on the Nile Nov 10, 2025

- Nov 10, 2025 Why Ancient Egyptian Houses Were Surprisingly Advanced Nov 10, 2025

- Nov 9, 2025 5 Hidden Details in the Temple of Hathor Stairs? Nov 9, 2025

- Nov 9, 2025 What Happened to the Great City of Memphis? Nov 9, 2025

- Nov 8, 2025 Why Did Egyptians Build a Pyramid Inside a Pyramid? Nov 8, 2025

- Nov 7, 2025 5 Things to Know Before Visiting Edfu Temple Nov 7, 2025

- Nov 7, 2025 Why Egyptian Wall Paintings Still Dazzle Historians Nov 7, 2025

- Nov 6, 2025 Ancient Egyptian Art and Culture: a Beginner’s Guide Nov 6, 2025

- Nov 5, 2025 7 Mysteries Hidden in the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut Nov 5, 2025

- Nov 5, 2025 Top 5 Largest Egyptian Statues: Names and Places Nov 5, 2025

- Nov 3, 2025 How Was the Pyramid of Giza Constructed Without Modern Tools? Nov 3, 2025

- Nov 3, 2025 Is Abu Simbel Egypt’s Most Impressive Temple? Nov 3, 2025

- Nov 3, 2025 What Does the Map of Ancient Egypt Really Tell Us? Nov 3, 2025

- Nov 2, 2025 Lamassu Pair, Khorsabad: Why five legs? Nov 2, 2025

- Nov 2, 2025 Ishtar Gate Lion Panel: Why one lion mattered? Nov 2, 2025

- Nov 2, 2025 Why do Sumerian votive statues have big eyes? Nov 2, 2025

- Nov 1, 2025 Dur-Sharrukin: Why build a new capital? Nov 1, 2025

- Nov 1, 2025 Standard of Ur: War and Peace in Inlay Nov 1, 2025

-

October 2025

32

- Oct 31, 2025 Dying Lion Relief, Nineveh: Why so moving? Oct 31, 2025

- Oct 31, 2025 Did the Hanging Gardens of Babylon exist? Oct 31, 2025

- Oct 30, 2025 Groom Leading Horses: What does it depict? Oct 30, 2025

- Oct 30, 2025 How did the first cities form in Mesopotamia? Oct 30, 2025

- Oct 29, 2025 What was Etemenanki, the Tower of Babel? Oct 29, 2025

- Oct 29, 2025 Standard of Ur: What do War and Peace show? Oct 29, 2025

- Oct 28, 2025 Foundation Figure with Basket: What is the ritual? Oct 28, 2025

- Oct 28, 2025 Mask of Warka (Uruk Head): The First Face Oct 28, 2025

- Oct 27, 2025 Eannatum Votive Statuette: Why hands clasped? Oct 27, 2025

- Oct 27, 2025 What are the famous Assyrian reliefs? Oct 27, 2025

- Oct 26, 2025 Gudea Statue: Why use hard diorite? Oct 26, 2025

- Oct 26, 2025 Bas-relief vs high relief: what’s the difference? Oct 26, 2025

- Oct 25, 2025 Ishtar Gate’s Striding Lion: Power in Blue Oct 25, 2025

- Oct 25, 2025 Vulture Stele: What battle and gods are shown? Oct 25, 2025

- Oct 24, 2025 What does the Stele of Hammurabi say? Oct 24, 2025

- Oct 24, 2025 Temple of Inanna, Uruk: What remains today? Oct 24, 2025

- Oct 23, 2025 Etemenanki: What did it look like? Oct 23, 2025

- Oct 23, 2025 What is Mesopotamian art and architecture? Oct 23, 2025

- Oct 22, 2025 Why is the Ishtar Gate so blue? Oct 22, 2025

- Oct 22, 2025 Ishtar Gate: Which animals and why? Oct 22, 2025

- Oct 21, 2025 Stele of Hammurabi: What does it say and show? Oct 21, 2025

- Oct 21, 2025 Lamassu of Khorsabad: The Five-Leg Illusion Oct 21, 2025

- Oct 20, 2025 Ziggurat of Ur: What makes it unique? Oct 20, 2025

- Oct 20, 2025 What is a ziggurat in Mesopotamia? Oct 20, 2025

- Oct 13, 2025 Su Nuraxi, Barumini: A Quick Prehistory Guide Oct 13, 2025

- Oct 12, 2025 Nuraghi of Sardinia: Bronze Age Towers Explained Oct 12, 2025

- Oct 10, 2025 Building With Earth, Wood, and Bone in Prehistory Oct 10, 2025

- Oct 8, 2025 Megaliths Explained: Menhirs, Dolmens, Stone Circles Oct 8, 2025

- Oct 6, 2025 Homes Before Houses: Huts, Pit Houses, Longhouses Oct 6, 2025

- Oct 5, 2025 Prehistoric Architecture: From Shelter to Symbol Oct 5, 2025

- Oct 3, 2025 Venus of Willendorf: 10 Fast Facts and Myths Oct 3, 2025

- Oct 1, 2025 Hand Stencils in Rock Art: What, How, and Why Oct 1, 2025

-

September 2025

5

- Sep 29, 2025 Prehistoric Sculpture: Venus Figurines to Totems Sep 29, 2025

- Sep 28, 2025 From Hands to Geometry: Reading Prehistoric Symbols Sep 28, 2025

- Sep 26, 2025 Petroglyphs vs Pictographs: The Clear Field Guide Sep 26, 2025

- Sep 24, 2025 How Rock Art Was Made: Tools, Pigments, and Fire Sep 24, 2025

- Sep 22, 2025 Rock Art: Prehistoric Marks That Changed Reality Sep 22, 2025