Doric Column: The Simplest Greek Order in Plain Language

Up close, Doric columns feel muscular and heavy, their flutes catching light like tendons so the whole temple reads as a tense, living body in stone.

If you have ever stood in front of a ruined temple and thought, “Nice columns… but which order is this again?”, you are not alone. The Doric column is usually the first classical order we meet in class, and yet it often stays a bit abstract: “simple, masculine, no base.” Helpful, but not quite enough to spot it confidently on site or in plan. In this guide, we slow down and walk around the Doric column together, so it turns from a vague label into a form you can actually recognise in ruins, drawings and photos.

By the end, you should be able to look at a façade, scan the columns and say “yes, this is Doric” in a few seconds, and also understand why Greeks picked this order for certain buildings and not others.

What is a Doric column?

A Doric column belongs to the Doric order, one of the three main Greek “families” of architecture that combine columns and the horizontal parts above them into a consistent system.

A quick mental picture: think of the Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis. Those sturdy, fluted columns without bases, topped by simple capitals and a frieze cut into alternating triglyphs and metopes, are the classic Greek Doric look.

At its most basic, a Greek Doric column has three key features:

No base: the shaft sits directly on the temple platform (stylobate).

Fluted shaft: a slightly tapered vertical cylinder with about twenty shallow, sharp-edged flutes.

Simple capital: a round “cushion” (echinus) that swells out and then supports a flat square block (abacus).

Above the column, the Doric entablature continues the order: a plain architrave, then a frieze made of triglyphs (three vertical bars) shifting with metopes (square panels that could be plain or sculpted), and finally a projecting cornice. Even if the sculpture is gone, that triglyph–metope rhythm is a strong Doric signal.

Definition: A Doric column is a fluted, usually base-less Greek column with a simple capital and a triglyph–metope frieze above it.

Historically, Doric appears early and is strongly linked to mainland Greece and western colonies. When you read broad overviews of ancient Greek art or Greek architecture, Doric temples tend to anchor the Archaic and Classical periods: firm, clear, and a bit severe. That character is part of why later architects, from Romans to Neoclassical designers, kept returning to it whenever they wanted a sense of strength and simplicity.

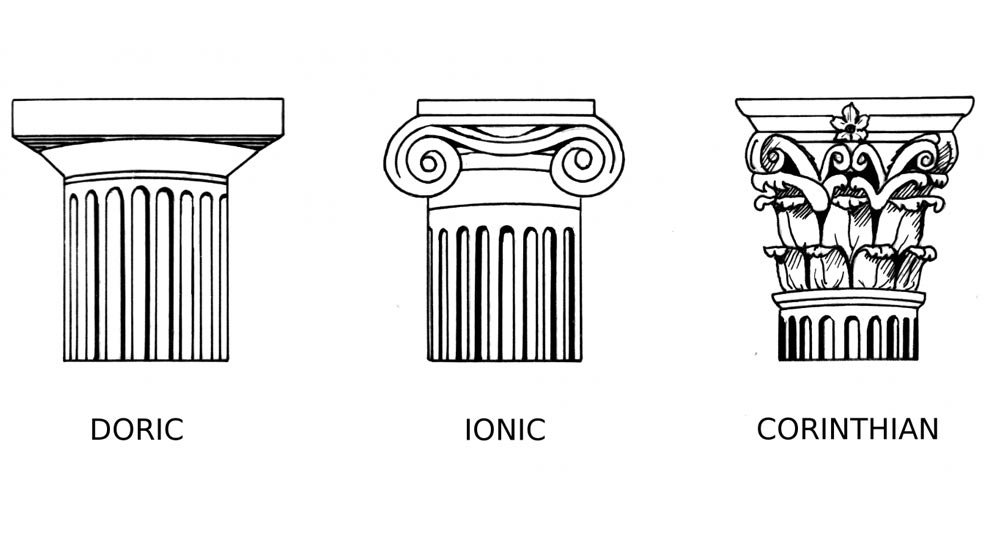

A clean diagram sets Doric, Ionic and Corinthian capitals side by side, making the jump from sturdy to ornate instantly readable.

How to recognise a Doric column at a glance

For everyday use, you do not need all the technical vocabulary. You mainly need a fast checklist that differentiates Doric from Ionic and Corinthian when you are scrolling museum photos or standing in front of a ruin.

A good starting trick is to line it up mentally with the other types of columns:

Doric: chunky, no base, simple capital.

Ionic: slimmer, with spiral volutes on the capital and a clear base.

Corinthian: very ornate capital with acanthus leaves.

For Doric specifically, try this quick scan from bottom to top:

Look at the feet

Are the columns rising straight out of the floor block with no extra ring or moulding? That “no base” situation usually points to Greek Doric. If you see a stacked base, you are likely in Ionic or Corinthian territory.Check the shaft

Doric shafts are quite sturdy in proportion: height is roughly four to eight times the diameter, so they feel stockier than other orders. The flutes are narrow and meet in sharp edges, which catch light strongly in the sun. This sharpness makes Doric temples look crisp even when weathered.Read the capital

Instead of volutes or leaf crowns, you just get a smooth swelling torus (the echinus) and then a flat square. In many early Doric buildings this echinus is quite wide and cushion-like; by the Classical period, as on the Parthenon, it becomes more restrained and tightly profiled.Glance at the frieze

Above the plain architrave, Doric friezes alternate triglyphs and metopes. Even if the sculpture inside the metopes is lost, the pattern of vertical bars and gaps is very distinctive. It is also what makes the Doric order so easy to spot in elevations and sections of Greek temples.

Because the Doric order is quite strict, it is a good training tool. Once you have practised on Doric, the slightly more complex ionic columns and later ornate forms feel less intimidating. Doric becomes like learning major chords on a piano before you move into jazz harmony.

Where you meet Doric columns in Greek architecture

Greek Doric columns are not just a detail; they help define whole building types and even regions. When you walk through an overview of ancient Greek structures, the big temples that anchor a sanctuary are very often Doric, especially in mainland Greece and in the western colonies of southern Italy and Sicily.

Some classic examples to have in your mental gallery:

The Temple of Hera at Olympia: early, relatively heavy Doric with strong, wide capitals.

The temples at Paestum in Italy: almost textbook Archaic Doric, powerful and low, showing how the order travels with Greek settlers.

The Parthenon in Athens: the famous high Classical refinement of Doric, with more slender proportions, careful curvature of the stylobate and subtle entasis (a slight swelling) in the shafts.

All of these stand on a continuum that runs back to simpler wooden forms. The triglyphs and guttae (the little pegs under them) are often read as fossilised memories of earlier timber beams and pegs. So a Doric column is not only a structural element; it is also a compressed history of building, recording how stone architecture grew out of earlier materials.

You will also find Doric columns shaping smaller constructions: treasuries in pan-Hellenic sanctuaries like Delphi, stoas around market squares, and sometimes even elements in domestic or civic contexts, which you can connect to your understanding of ancient Greek city-states and their public spaces.

Later, in Roman and Neoclassical architecture, Doric is constantly rewritten. Sometimes it gains a base, sometimes the flutes disappear, but the basic “sturdy shaft + simple capital” vibe persists. So learning the Greek Doric version gives you a baseline to recognise all these later, more hybrid interpretations and to see how designers negotiated between clarity and decoration.

The Parthenon’s Doric columns catch sharp Greek sunlight, turning a ruined temple into a lesson in rhythm, mass and proportion.

Conclusion

If we strip away all the jargon, a Doric column is simply the Greek way of saying “strong, clear and grounded” in built form. No base, a fluted shaft, a straightforward capital and a disciplined frieze rhythm above: together these elements create a look that is both minimal and expressive. Once you have that visual grammar in your head, façades and ruins stop being anonymous rows of stone and start reading like sentences.

As you keep exploring Greek architecture and ancient Greek art more broadly, you will see Doric columns set next to other orders, on different building types and in different regions. Try to notice not just “is this Doric or not?”, but also why someone might have chosen this order for a particular temple, treasury or stoa. That question connects a simple column on site with the larger cultural choices behind it.