Minoan Wall Paintings: Bulls, Dancers and Island Landscapes

The Spring Fresco wraps an entire room in flowers and birds, showing how wall painting could turn domestic space into an immersive landscape on Bronze Age Thera.

Imagine walking through a Minoan palace with no glass cases and no ruins. Just white plaster walls exploding with colour. A bull stretches across a whole panel. Dancers bend in impossible curves. Red rocks and blue sea wrap around the upper walls like a continuous horizon. You are not just in a building; you are inside a painting.

That is what Minoan frescoes once did on Crete and nearby islands. They turned walls into moving stories about animals, rituals, landscapes and maybe even myths. Today we meet them as fragments: a leaping bull here, a woman with curling hair there, a strip of lilies in a museum. In this guide we will put some of those pieces back together.

We will ask what Minoan wall paintings are, how they were made, what bulls and dancers are doing on them, and what the island landscapes from Akrotiri add to the picture. If you want more context on the people and buildings behind them, you can also read our overview of Minoan civilization and our explainer on Minoan palaces, where these paintings originally lived.

Minoan frescoes turn palace walls into colourful narrative space

Minoan wall paintings are not small framed pictures. They are frescoes, images painted on a layer of wet plaster so that pigments sink in and bond as the wall dries. In practice, Minoan painters mix techniques: some areas go onto fresh plaster, others onto dry, but the result is the same for us today – colour that still clings to the surface after three and a half thousand years.

These frescoes cover important interior and exterior walls at sites like Knossos, Phaistos and Malia, and in elite houses at Akrotiri on Thera. They run as friezes high on the wall, fill full-height panels between columns, or wrap entire rooms in continuous scenes. Floors and ceilings could be painted too. That means when you entered certain spaces, you stepped into a world where architecture and painting worked together, not separately.

The palette is limited but bold. Painters use strong blues, reds, whites, yellows and blacks. They outline figures with dark lines, then fill them with flat colour. Men are usually painted with darker skin, women with lighter, following a broader eastern Mediterranean convention. Backgrounds can be plain or busy, depending on whether the focus is on bodies, objects or landscape. The style often feels energetic and fluid; there is less concern with strict perspective, more with rhythm and pattern.

We should also keep in mind that what we see now has been heavily restored. Early excavators at Knossos, especially Arthur Evans, allowed modern artists to reconstruct missing parts. Some famous images, like the so called “Prince of the Lilies”, are now treated with caution because the joins between ancient and modern are not always clear. That is why many recent discussions of ancient Minoan art focus on well documented fragments and on sites like Akrotiri, where the reconstruction process has been more conservative.

Definition: Minoan frescoes are wall paintings created on plastered surfaces in Bronze Age Crete and nearby islands, decorating palaces and elite houses with colourful scenes of people, animals and landscapes.

The lively Blue Monkeys fresco reminds us that Aegean art was full of playful, exotic animals as well as ritual scenes and palaces.

Bulls and acrobats: what is happening in the bull-leaping scenes?

If you have seen only one Minoan painting, it is probably a bull-leaping fresco. A huge bull charges across the panel, and human figures flip over its back. Hair, tails and limbs curve in parallel arcs. At Knossos, this scene decorates a long panel now known simply as the Bull-leaping fresco.

The basic motif is clear: humans and a bull involved in a risky acrobatic act. One person grasps the bull’s horns at the front, another flies through the air above the back, a third stands at the rear, arms extended. Figures with darker skin are generally read as male, lighter ones as female, but the clothing is similar: tight belts, short kilts or skirts, bare torsos in many cases. We are not looking at a casual farm chore. This is staged performance.

What the scene means is more debated. Some scholars see it as a religious ritual, possibly tied to rites of passage, fertility or displays of elite courage. Others argue for a sport that had both entertainment and political value, like a combined festival and power show. There are no labels or captions in a readable script to settle the question, and we do not have enough examples to track a clear narrative sequence. What we can safely say is that bulls were central symbols in Minoan culture and that dangerous, highly controlled interaction with them mattered enough to paint on palace walls.

From an art perspective, the bull-leaping scenes show off everything Minoan painters do well. They combine strong outlines, curved motion and stylised anatomy to create a sense of extreme movement. The bull’s body stretches into a long, flexible rectangle. Human spines bend in impossible arcs that make the flip feel almost weightless. The background is often plain, so nothing distracts from the action. If you want to go deeper on this specific topic, our article on Minoan bull-leaping slows down on the details and the open questions.

Myth vs Fact

Myth: Bull-leaping frescoes literally show the Minotaur story inside the labyrinth.

Fact: Bull-leaping scenes predate later Greek myths and most likely depict real or ritualised bull sports, not the Minotaur legend.

Dancers, women and gatherings: people as main characters, not background

Bulls are only part of the fresco story. Many Minoan wall paintings put human figures front and centre, especially women with elaborate hairstyles and layered dresses. One famous example is the so called “La Parisienne” from Knossos, a profile of a woman with curling hair, red lips and a patterned garment, captured mid-gesture as if she is about to speak or sing. She probably formed part of a larger procession or ritual scene.

Elsewhere, we see long lines of people bringing offerings, musicians playing, or groups watching performances. In miniature frescoes, crowds fill stepped stands, suggesting that palace courts could host large gatherings. Clothes are colourful and detailed. Belts pinch waists tightly. Skirts flare in tiers. Men often wear kilts or loincloths, sometimes with boots or sandals. These details are not there just to show off fashion. They help mark roles, status and movement. A figure holding a libation vessel and framed by symbols will read differently from someone standing in a crowd.

Gender roles in these images are complex. Women appear as priestly figures, musicians and participants in ceremonies, not just passive onlookers. Men show up as athletes, attendants and sometimes as more anonymous crowd members. Because we cannot read most Minoan inscriptions, we have to avoid overconfident statements about who held which powers. Still, the visual balance suggests that Minoan paintings valued both female and male presence in public ritual scenes.

In more intimate settings, such as small shrine rooms or bench sanctuaries, fresco fragments show isolated symbols, rosettes, griffins or single worshippers. Here the wall painting narrows the focus. Instead of a whole festival, we get a concentrated image of a deity’s attribute or a key moment of offering. Together with the large ceremonial scenes, these smaller panels make Minoan palaces feel like image-dense environments, where almost every important space has something painted to guide the eye and set the mood.

Island landscapes at Akrotiri: nature as more than a backdrop

If Knossos is where we meet bulls and palace crowds, Akrotiri on Thera is where Minoan-style painting fully embraces landscape. This Bronze Age town, buried by a volcanic eruption and excavated in the twentieth century, preserves rooms where walls are almost entirely covered by rocky coasts, plants, birds and people moving through them.

In the “Spring Fresco”, red and yellow rocks rise in looping forms, dotted with lilies and visited by swallows. There are no human figures, just an intense, almost musical landscape. In the “Crocus Gatherers” and related scenes, young women pick flowers from rocky slopes and present them to a central female figure, sometimes interpreted as a goddess. Elsewhere, flotillas of ships move between stylised harbours, linking coastal towns in a continuous frieze.

These images tell us a few important things about Minoan and Minoan-influenced painting. First, nature is not just background decoration. Rocks, plants and animals are active partners in the scene. They curve and repeat, almost like dancers themselves. Second, the island setting matters. Steep coasts, narrow paths and visible sea routes are built into the visual language. This fits with what we know about island life in the Aegean from archaeology: communities that live close to cliffs, terraces and harbours.

Akrotiri is Cycladic rather than Cretan, but its wall paintings are closely related in style and technique to those on Crete. Many scholars treat them as part of the wider Minoan art world, or at least as a sister tradition. For our purposes, they expand what “Minoan frescoes” can mean. It is not only bulls and palaces. It is also quiet rooms filled with lilies, children boxing, fishermen carrying their catch, and fleets crossing a painted sea.

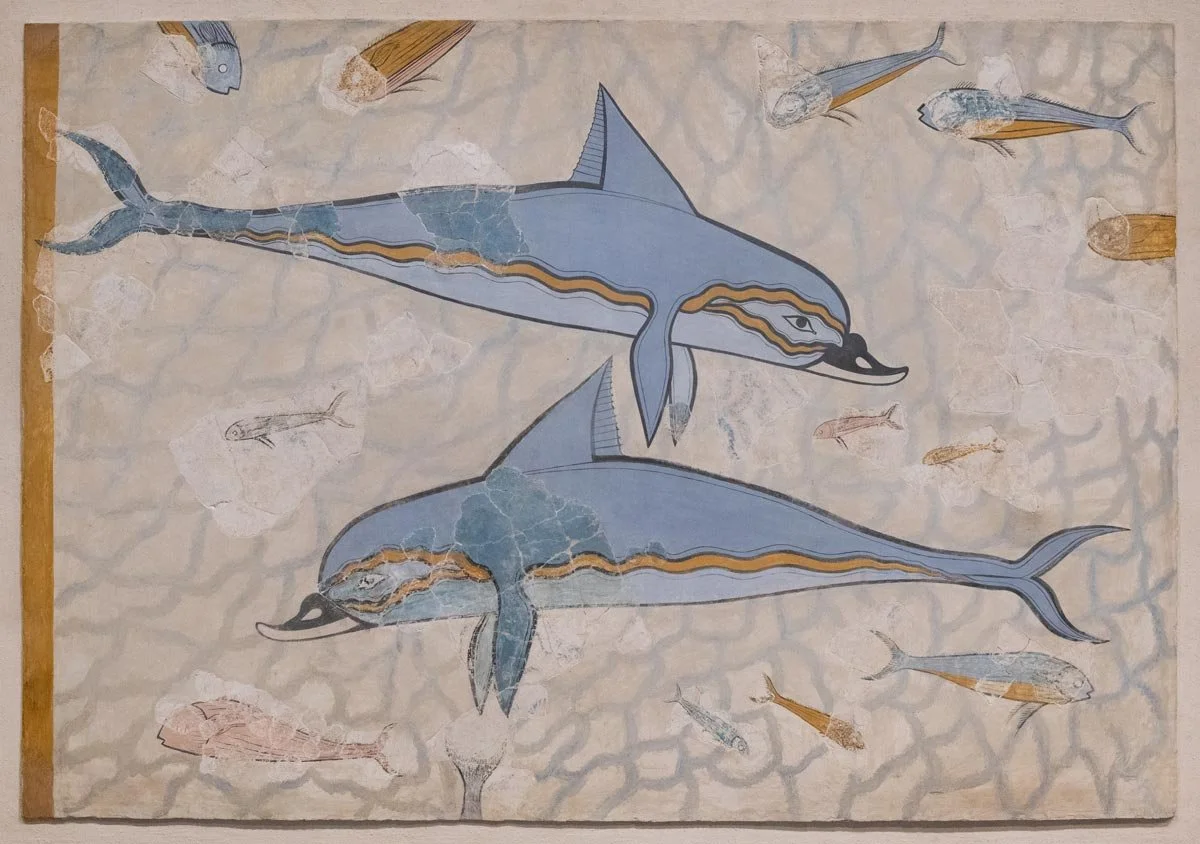

The Dolphin Fresco from Knossos brings the sea indoors, hinting at how closely Minoan palaces were connected to maritime life.

How to look at a Minoan wall painting today

Most of us will never walk through a fully painted Minoan palace. We meet these works in fragments in museums, books and screens. So how do we look at a fresco in Minoan art in a way that does it justice.

A simple method is to move in three passes. First, take in the overall rhythm. Step back and notice where the main lines run: horizontal bands, big curves, repeating shapes. Frescoes were meant to be seen at some distance, probably in motion as you walked through a space. That rhythm is part of the message.

Second, go closer and pick out figures and details. How are bodies drawn. Which way do they face. What are they holding. Are there clues about gender, role or action. In bull-leaping scenes, for example, just checking where each body is in the jump can open questions about what is happening before and after the moment frozen in paint.

Third, zoom out again and imagine the original room. Was this in a palace hall, a stairwell, a small shrine, a private house. Our article on Minoan palaces can help with that step. A bull-leaping panel in a grand court reads differently from the same motif in a side room. A peaceful landscape in an upstairs bedroom has a different tone from one in a public reception space.

For me, the most beautiful thing about Minoan frescoes is how they refuse to separate art from life. Bulls, dancers and island cliffs are not museum subjects yet. They are the things people see, fear and celebrate every day, painted right onto their walls. If this guide helps you feel even a little of that everyday vividness, it has already done good work.

Sources and Further Reading

Metropolitan Museum of Art — “Minoan Crete” (2002) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Smarthistory — “Minoan art, an introduction” (2020) (Smarthistory)

Khan Academy — “Minoan art, an introduction” (2020) (Khan Academy)

Smarthistory — “Bull-leaping fresco from the palace of Knossos” (2020) (Smarthistory)

Khan Academy — “Bull-leaping fresco from the palace of Knossos” (n.d.) (Khan Academy)